|

Fort McClary

Kittery Point, Maine, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1808 - 1868

Used by: United States of America

Conflicts in which it participated:

Manned from the War of 1812 through the Second World War:

Never attacked

|

The Piscataqua River, which today marks the border betwixt Maine and New Hampshire and o'er which Fort McClary and other forts stand sentinel, was first poked at by the white man in 1603, in the form of English explorer Martin Pring (1580-1626) and his merry shipmates. 'Twas upon this river that the first sawmill in the New World was built, in 1623.

|

|

|

|

What would become the city of Portsmouth, New Hampshire was settled on the western bank of the Piscataqua in 1630. Around 1682 the largest house in what was then Massachusetts' Maine district was built across the river from Portsmouth, for local merchant and shipwright William Pepperrell (d. 1733). Pepperrell bought a tract of land adjacent to his property in 1689 called "Battery Pasture," which suggests that there may have been guns stationed there previously. Upon this land, overlooking the Piscataqua River and facing Fort William and Mary, Pepperrell constructed some form of defensive earthworks. By the end of the 17th century he would own most of the town of Kittery, and had a vested interest in the defense of Portsmouth and its blooming shipping industry from whatever shipborne entity might wish it ill.

|

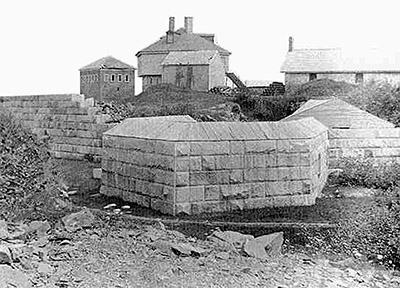

Fort McClary circa 1900, in front of its Civil War-era bastion addition. Fort McClary circa 1900, in front of its Civil War-era bastion addition. |

|

Around 1720, a permanent, six-gun battery was built at this spot, at the behest of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. A "Naval Officer" was stationed at this battery, who would extract a duty from all ships entering the harbor. This cash was used to purchase powder and shot for the battery, which was known as Fort William (not to be confused with Fort William and Mary), named for William Pepperrell.

The Pepperrell family remained loyal to the Crown during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), and was rewarded by having their lands confiscated by local patriots. New Hampshire militia manned the guns of Fort William until 1779, when they got bored and left. |

|

Maine remained a part of Massachusetts until 1820, and thus it was in 1803 that the US government ceded 1.87 acres of land on the banks of the Piscataqua to the state of Massachusetts, for the construction of a proper fort to enhance the defendin' power of Fort Constitution (the fort previously known as Fort William and Mary) in the defense of Portsmouth. This was the spot on which Fort William had been built, upon which Fort McClary would be constructed.

|

Named for Revolutionary War hero, and New Hampshire native Major Andrew McClary (one of many who acquired hero status by being killed by the British at the Battle of Bunker Hill (June 17, 1775): Fort Warren in Boston Harbor was also named for such a hero), Fort McClary initially consisted of two batteries, which were creatively named the Lower Battery and the Upper Battery. Fort McClary's Lower Battery was impressively armed with five 32-pounder guns and four 8-inch howitzers, plus a hot shot furnace, the apex of 1808 seacoast artillery technology. The Upper Battery was never armed (kind of making a mockery of the term "battery"), but a series of brick buildings were built up there, including the Powder Magazine, which still stands today. |

|

Fort McClary's one remaining Rifleman's House (left) and Powder House (right), both dating from 1808, and the blockhouse, built in 1844, behind. Fort McClary's one remaining Rifleman's House (left) and Powder House (right), both dating from 1808, and the blockhouse, built in 1844, behind. |

|

Two Rifleman's Houses were built to provide flank defense for the Upper Battery: An attacker climbing that hill would have to contend with riflemen firing at them through the tiny windows of two solid brick houses: One of these structures still (mostly) stands today.

|

Fort McClary's Blockhouse, built in 1844. The Lower Battery is visible below. Y'know, where one would expect to find a Lower Battery. Fort McClary's Blockhouse, built in 1844. The Lower Battery is visible below. Y'know, where one would expect to find a Lower Battery. |

|

Fort McClary's most distinctive edifice, its Blockhouse, was built in 1844. This fortification had an underground powder magazine at its base; A ground level rifle gallery, with firing slits in granite walls; Six 12- or 24-pounder Carronades mounted on the second level, and sumptuous Officers' Quarters on the third level.

In 1846 the federal government bought an additional 25 acres to enlarge the base surrounding this, the last blockhouse built in Maine. Immediately thereafter, Fort McClary was deactivated. Surprise!

Fort McClary sat, alone and unloved, for the next fifteen years. Fortunately another war came along in 1861 to make things interesting again! |

|

The onset of the US Civil War (1861-1865) freaked everybody out, not the least of which Portsmouth New Hampshire, the destruction of which was the number one strategic objective of the Confederacy. Well. Maybe not, but Portsmouth was a major force in the US shipbuilding industry, so it was certainly within the bounds of reason to think that it might be a target of a nation at war with the United States. Four 32-pounder naval cannon from the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard were dragged to Fort McClary's Lower Battery, where they were eagerly manned by a variety of artillery units over the course of the war. This duty was doubtless extremely exciting, as the Confederacy never made its inevitable move on Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Hannibal Hamlin (1809-1891), Vice President from 1861 to 1865 under Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865), was a resident of Maine, and a member of a Maine Coast Guard militia unit. His unit was called up for garrison duty at Fort McClary in 1864, and instead of doing what one would expect of a sitting Vice President of the United States of America (which is stay right where he was and continue to wait for the President to die), dude reported for duty and served as company cook at the fort of our current interest from June to September.

Even the chance of snuffing the Veep couldn't tempt the Southrons into an attack on Fort McClary, but the Confederate Navy was present off the coast of New England during the war. |

|

Fort McClary's awesome bastion, what was to be one of a pair. And my sister. The fort's well is center front. Fort McClary's awesome bastion, what was to be one of a pair. And my sister. The fort's well is center front. |

The CSS Alabama, a British-built screw sloop of the Confederate Navy, spent a relaxing couple of months in 1862 sailing up and down the coast of New England, capturing and burning ten ships that may or may not have had anything to do with the war effort. This seemed to illustrate the vulnerability of these waters, causing a delightful overreaction by no less of a fortification expert than Joseph Totten (1788-1864). Totten, American military engineer numero uno who had overseen the construction of spectacular starfort Fort Adams at Newport, Rhode Island (among many other fortification projects), determined that it was absolutely imperative that Maine be immediately furnished with SUPERDUPERFORTS!!! to protect its coastline from marauding, blood-sucking Confederates. |

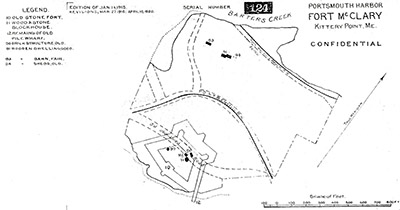

Thanks to FortWiki.com for this top-secret 1915 plan for Fort McClary's fanciful upgrade!! Thanks to FortWiki.com for this top-secret 1915 plan for Fort McClary's fanciful upgrade!! |

|

Plans were drawn up for a massive reworking of both Fort McClary and Fort Constitution, across the channel. In Fort McClary's case, the end result was to be a masonry monster with two levels of casemates, similar to Fort Knox and/or Fort Popham, two other Maine forts. Work on Fort McClary's upgrade began in 1863. One of two planned bastions was added to the fort's northernmost corner, and a caponniere was constructed so as to stick out to the south, to deter anyone who might be interested in attempting to clamber up the fort's riverside sheer masonry face. |

|

A number of 10-inch Seacoast Parrot Rifles were mounted at Fort McClary's Lower Battery during this period, just in case someone would be so inconsiderate as to attack the new fort before it was finished. Several Rodman Guns also spent time defending Fort McClary during the war, many of which by lying, unmounted, on the ground. Perhaps this was psychological warfare: If an enemy sent in spies to see how the fort was armed, they would report back that there were so many guns available, a bunch of them were just dropped on the lawn!

|

Although the end of the immediate threat came with the end of the war in 1865, work continued on Fort McClary until 1868. At this time the money for this project suddenly dried up, and every man working on the fort dropped whatever he was holding and walked away. This left a dramatically incomplete wall on the fort's western side, and piles of granite blocks scattered untidily about. Only the first level of some of Fort McClary's walls had been completed.

In the early 1870's, it began to slowly dawn on the bearded men who were running things that many of America's seacoast defenses were in poor shape, and a brief, halfhearted effort was made to correct this. |

|

Fort McClary's other most distinctive edifice, its unfinished western wall. Fort McClary's other most distinctive edifice, its unfinished western wall. |

|

Very few of the projects begun during this period were actually completed, but in 1874 Fort McClary's Lower Battery was modified with three temporary wooden gun platforms...and then everybody's interest waned before anything could be put onto those platforms.

...until the glorious 1890's, which was the next time people became concerned about the state of America's seacoast defenses! Nine 15-inch, smoothbore Rodman Guns were delivered to Fort McClary in 1890, at which time they were unceremoniously dumped on the ground, where they remained for the next eight years.

|

Fort McClary's blockhouse, above a pile of granite blocks left where they were dropped in 1868. Fort McClary's blockhouse, above a pile of granite blocks left where they were dropped in 1868. |

|

These guns were the most impressive artillery in existence at the start of the US Civil War (the first 15-incher was cast in 1860, named The Lincoln Gun, and is currently on display at Fort Monroe at Hampton Roads, Virginia), but were pretty ridiculously obsolete 30 years later. Three of these Rodmans were finally mounted at Fort McClary's Lower Battery in 1898, when it was thought to be just a matter of time before the mighty Spanish swooped down upon each and every American seaport, irresistibly spitting death and destruction. The guns of Fort McClary were manned by a small detachment from Fort Constitution. Additional Rodmans and parrots were left lying around, so as to impress any attacking Spaniards. |

|

Fortunately for everybody except Spain, the Spanish Empire of 1898 was even more obsolete than a smoothbore Rodman Gun. The United States took the fight to Cuba and the Philippines, and Portsmouth, New Hampshire was saved. Fort Foster, composed of a couple of Endicott Period batteries, was built at the mouth of the Piscataqua from 1898 to 1904. Its modern guns protected Portsmouth far more effectively than Fort McClary's Civil War-era armament lying on the ground ever could, and all of Fort McClary's guns were sold off by 1910. Fort McClary's last official uses were during the First (1914-1918) and Second (1939-1945) World Wars. An adorable little observation deck was added to the top of the blockhouse, upon which alert individuals kept a keen eye on the horizon for the Kaiser's dreadnoughts during the First World War, and Japanese bombers during the Second. |

|

Some of Fort McClary's spare Rodman Guns and Parrot Rifles, around 1910. Some of Fort McClary's spare Rodman Guns and Parrot Rifles, around 1910. |

|

Today Fort McClary is open to the public, and is absolutely gorgeous, if one will forgive the editorial comment. The blockhouse was restored in 1987 and is and filled with great signage. While this fort never made it to full-blown superfort status, the caponniere (spelled 'caponier' for American forts, but the French is way cooler), into which a visitor can scamper, is a delightful suggestion of what might have been. I and my intrepid sister visited Fort McClary in April of 2015. Please proceed to the Fort McClary section of the Starforts I've Visited section at a speed commensurate to your level of interest.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|