|

Fort Warren

Georges Island, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1833-1861

Used by: USA

Conflicts in which it participated:

None

|

Approximately one hundred thousand years ago, glaciers showed up in what would one day be Boston Harbor and thoughtfully decided to leave a pile of disgusting glacier sediment which, many millennia later, became an island when sea levels rose.

Indians visited this island seasonally, collecting fish and other delicious things, until a gentleman by the name of James Pemberton showed up and began living on this island in 1628 (please note that this was not the James Pemberton who was a mayor of London and died in 1613). |

|

|

|

Logically this island became known as Pembertons Island. 'Twas renamed, however, Georges Island at the start of the 18th century after Boston bigwig Captain John George.

|

A colorful look at Georges Island today, which is pretty much all Fort Warren! A colorful look at Georges Island today, which is pretty much all Fort Warren! |

|

As Boston became the major shipping powerhouse for which it was famous the world over, those who paid attention to such things noted that Georges Island (which was then being used as pastureland for grazing beasts) commanded the Narrows, the channel through which shipping must pass to dock at Boston.

The French, of all people, were the first to build fortifications on Georges Island, in 1778. During the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) there was some semblance of a French fleet anchored at Boston, and the French built some temporary earthworks on Georges Island to prevent potential British naval wickedness. Unfortunately, the British declined the invitation.

In 1825 the city of Boston bought Georges Island from its private owner, and presented it to the US government. This government wasted no time in commencing to build an erosion-controlling seawall around their newest island. |

|

|

Colonel Sylvanius Thayer (1785-1872), the Father of West Point, resigned from his position as superintendent of that institution in 1833, after a disagreement with US President Andrew Jackson (1767-1845). Thayer had directed the defenses of Norfolk, Virginia during the War of 1812 (1812-1815), doubtless spending time at the semistarry fishyfort Fort Norfolk.

|

But the reason we're interested in Thayer in this circumstance is that, after leaving West Point, he resumed his previous work with the US Army Corps of Engineers and was put in charge of Boston's budding defensive system.

Any new American starfort needed a dead hero after whom to name it. Dr. Joseph Warren (1741-1775) was an eloquent American patriot who dispatched Paul Revere (1734-1818) on his fabled midnight ride on April 18, 1775, alerting the populace of the imminent arrival of the British. Warren was commissioned as a Major General of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), but died days later at the Battle of Bunker Hill (June 17, 1775) as a private soldier.

|

|

The Death of Joseph Warren at the Battle of Bunkers Hill by John Trumbull, who, unfortunately, is not the same Jonathan Trumbull after whom Fort Trumbull was named. Because that would just be too perfect. |

|

Unassuming, heroic fellow that he was, Warren had volunteered to defend the hill from the haughty British, who, upon finally overrunning the redoubt being held by the Americans at the top of the hill (which was actually called Breed's hill), reportedly bayonetted his corpse with wild abandon. Let's absolutely name a starfort after that guy!!

|

Fort Warren's main gate, circa 1861. |

|

Thayer's zealous oversight had Fort Warren virtually completed by 1858. When the US Civil War (1861-1865) broke out, however, plenty of construction detritus still littered the fort's parade ground, and the grand total number of guns that had been mounted was zero. Massachusetts Governor John Andrew (1818-1867) said eek and arranged to have big guns (and troops to man them) installed at Fort Warren forthwith.

During the war Fort Warren served as Boston Harbor's main defensive position and as a recruiting and training center for Union troops, but is remembered mostly as a Prisoner of War Camp. |

|

|

Such vicious Confederates as the Mayor of Baltimore, the Governor of Kentucky and members of the Maryland Legislature were held at Fort Warren at the beginning of the war. The two Confederate diplomats who had been plucked from a British ship heading for London by the US Navy in the Trent Affair (over which Great Britain considered declaring war on the United States) were imprisoned for a time at Fort Warren, as was Alexander Stevens (1812-1883), Vice President of the Confederate States of America. Mr. Stevens spent his time at Fort Warren after the war, of course. Great, thought Stevens, Jefferson Davis (1808-1889) gets to be imprisoned at Fort Monroe, and all I get is Fort Warren!!

|

While prison life is never particularly pleasant for anybody, Fort Warren's commanding officer, Colonel Justin Dimick, had served with many of his inmates in the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), and made efforts to ensure that they were as comfortable as possible, given the circumstance. Dimick was so well regarded by his prisoners that, when his son headed into battle with the 2nd US Artillery, he did so with a letter signed by several Confederate officers requesting good treatment of the younger Dimick if captured.

Fort Warren was designed to mount 200 guns, but of course never approached that number. As always, the amount of time it took to design and build the fort ensured that the cannon which the fort had been designed to mount would have been vastly outclassed by the time they were mounted.

|

|

A mighty Rodman Gun overlooking Fort Warren's main gate. A mighty Rodman Gun overlooking Fort Warren's main gate. |

|

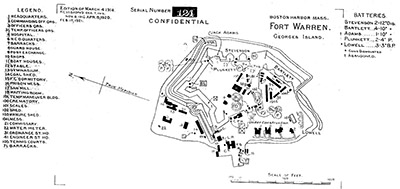

The cannon that did eventually get mounted at Fort Warren were mostly arrayed along the barbette tier. This is the long berm that snakes alongside the left of the fort in the image at the top of this page, which is the side that faces the Narrows as the fort lies. There are mounts in place to cover other directions, but plainly it was thought that enemy ships would placidly sail before only the north of the fort.

|

Oh, snow. Oh, snow. |

|

One of Fort Warren's lasting contributions to the American military tradition is that the song John Brown's Body, which was transmogrified into The Battle Hymn of the Republic, was created therein.

John Brown (1800-1859) was an abolitionist sociopath who tried to incite a slave rebellion in the American south by killing lots of people and attempting to seize the federal arsenal at Harper's Ferry, Virginia (October 16, 1859), and was executed by the US government. |

|

At the beginning of the Civil War, Union troops of the Second Battalion of Infantry were detailed to remove the aforementioned building detritus from Fort Warren's parade ground. There was a Private in the Second Battalion also named John Brown, who was naturally the object of much teasing. As he and his compatriots dragged endless piles of bricks, tools and granite here and there, they reasoned that he couldn't be John Brown, because John Brown's body lies a-mouldering in the grave...but his soul goes marching on! They had been singing a hymn called "Say, Brothers, Will You Meet Us?" and added their new, dead-body-related words to the tune.

John Brown's Body was a catchy ditty indeed, and as troops trained at Fort Warren and then headed off for active duty, they brought the song with them. It became one of the Union's most popular marching songs during the war, but its lyrics were somewhat coarse (as befits a song sung by marching troops!). A little later in the war, author Julia Ward Howe (1819-1910) wrote the lyrics to that same stirring tune, which became The Battle Hymn of the Republic.

|

A top-secret plan of Fort Warren from 1914 wait 1916 no 1920 okay 1921. Tennis courts. Thanks, Fortwiki.com! A top-secret plan of Fort Warren from 1914 wait 1916 no 1920 okay 1921. Tennis courts. Thanks, Fortwiki.com! |

|

Fort Warren was the beneficiary of some of the first construction of the Endicott Period, the process by which America's seacoast defenses were dragged into the 20th century. As the first of many batteries to be built, however, it became obvious that the Army Corps of Engineers hadn't quite figured out what it was doing in 1892. The first, Battery Adams, is visible as the mount closest to the top of the image at the head of this page. |

|

Battery Adams was named for John G. B. Adams (1841-1900), who was awarded the Medal of Honor for bravery at the Battle of Fredericksburg (December 11-12, 1862) during the US Civil War. Hopefully Adams was never told that the battery named in his honor, designed to mount a 10" Disappearing Gun, was determined to be unworkable shortly after completed.

Similarly, Battery Bartlett, named for General William Francis Bartlett (1840-1876), a Massachusetts native who was wounded four times during the US Civil War, was built with inferior cement. Visible as the outer battery to the center right of the image at top, Battery Bartlett was built to mount four 10" Disappearing Guns.

|

Boston Harbor was mined when the Spanish American War (1898) broke out, and Fort Warren was fully manned in expectation of the mighty Spanish Armada's imminent arrival. Fort Warren served as the harbor's Mine Command Center during the First World War (1914-1918), and again during the Second World War (1939-1945). Fortunately Benito Mussolini (1883-1945) never sent his navy's chuffing submarines after Boston, so neither mines nor their control proved necessary.

Fort Warren was decommissioned in 1946, and named a National Historic Site in 1958. Since 1996, Georges Island has been part of Boston Harbor Islands National Park, and is open for visits each year during the Boston Harbor Ferry's operating season (May through early September).

|

|

Battery Plunkett's two 4" Rapid-Firing Guns around 1915, clearly not mounted at Battery Plunkett, likely used as amusing decoration outside the fort's main gate. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|