|

Fort Constitution

New Castle, New Hampshire, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1800-1808

Used by: USA

Conflicts in which it participated:

None

|

While Fort Constitution was so scary it went unchallenged, a 1774 attack on the previous fort at this site, Fort William and Mary, just may have been the first directly hostile act of the American Revolution.

English explorer Martin Pring (1580-1626) was the first European to poke up the Piscataqua River to what is now the city of Portsmouth, in 1603. |

|

|

|

English settlers landed on the west bank of the Piscataqua in 1630, naming it Strawberry Banke, due to both the wild strawberries that grew there, and their unwillingness to spell the word "bank" correctly. By 1632, the British had built The Castle, an earthen redoubt armed with four guns, on a spit of land jutting into the river, to protect the flourishing port. In 1692 'twas renamed Fort William and Mary, enlarged to mount 19 guns and serve as the colony of New Hampshire's primary munitions depot.

The town of Portsmouth was incorporated in 1653, named not for the obvious fact that it's at the mouth of a port, but in honor of the colony's founder, John Mason (1586-1635). Mason had been "captain" of the port of Portsmouth, Hampshire, England...and since the colony was named New Hampshire, naturally its capitol would be named either Masonville or Portsmouthvilletowne, but for some reason they went with Portsmouth.

During the French and Indian War (1754-1763), canoe-borne warriors of the Wabanaki Confederacy raided Kittery Point, Maine, on several occasions. Kittery Point is right across the Piscataqua from Portsmouth, thus Fort William and Mary was considered well-placed to "protect" Kittery Point from such ne'er-do-wells. If there were several Indian raids, however, those Indians likely didn't feel particularly threatened by Fort William and Mary. And why on earth would they, it's a teeny thing with four teeny cannon and five teeny guys in it!

|

An Explanation on the Prospect Draft of Fort William and Mary on Piscataqua River in ye Province of New Hampshire on the Continent of America, 1705. One imagines it was easier to see in real life, than it is in this washed-out print.

From above, Fort William and Mary's appearance was much the same as Fort Constitution's! Sort of. From above, Fort William and Mary's appearance was much the same as Fort Constitution's! Sort of. |

|

Stone walls were added to Fort William and Mary in 1705, but during the Colonial period this fort was manned by fewer than 10 British soldiers for most of the year, with an additional 20 to 40 being stationed there in times of crisis, such as Summertime. Although one suspects that the crisis of Summertime was that it was the only pleasant time of year to actually be in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

During two separate night raids on December 14 and 15, 1774, some 400 members of the local chapter of the Sons of Liberty stormed Fort William and Mary, non-lethally overcoming the British officer and five soldiers stationed there, to abscond with 16 small cannon and 97 barrels of gunpowder. |

|

|

A plaque commemorating the attacks on Fort William and Mary, at Fort Constitution's main gate. Click on it if you'd like to read it. |

|

This is considered the first heroic (violent) anti-British act of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783).

|

|

|

Some of the ordnance seized by the Patriots at Fort William and Mary eventually made its way to Boston, where it was used to lose (in an heroic fashion) to the British at the Battle of Bunker Hill (June 17, 1775).

The Royal Navy's 20-gun frigate HMS Scarborough and armed hydrographic survey sloop Canceaux arrived at Fort William and Mary a few days after the raids with around 100 Royal Marines, cutting short any further patriotic raid plans. Fearing its capture, the British partially dismantled the fort in May of 1775, but apparently not enough to prevent New Hampshire's British Governor, Sir John Wentworth (1737-1820), from seeking shelter there in June of 1775. Wentworth and whatever troops were stationed at Fort William and Mary sailed to Boston in August of 1775, which represented the end of British rule in New Hampshire.

Fort William and Mary saw little use during the rest of the war. After independence, it was referred to as "Castle Fort," and was armed with thirteen guns, seven of which were heavy naval guns of the 42, 24 and 18-pounder variety. Castle Fort primarily served as a customs collection station for the harbor, and a lighthouse post.

|

Construction on what would become a new fort commenced in 1800. 1802 saw the first mention of the name Fort Constitution in the documents of US Secretary of War Henry Dearborn (1751-1829), although the name wasn't made official until... 1937!!By 1808, the fort had new outer stone walls that were twice as high than had previously been the case, as well as a bastion facing the river and two brick barracks, capable of housing 150 men. This rebuild occurred during America's second system of seacoast defense, which makes if one of very few forts from this era still standing today.

|

|

Fort Constitution, not long after its completion. Fort Constitution, not long after its completion. |

|

But a disaster on July 4th, 1809, might have been the new fort's undoing. "About 300 weight" (over 100 pounds) of gunpowder had been set on one of Fort Constitution's walls to dry, and the fort's commander, Colonel John Baptiste de Barth Walbach (1766-1857), was hosting an Independence Day dinner party. Anyone who has experienced a July 4th celebration knows that there are many burning, fizzing things flying about in great number, and sure enough, the powder was mistakenly ignited. The explosion that resulted killed 14 people, and the concussion that Colonel Walbach experienced may help to explain his lapse in fortification judgement during the War of 1812 (1812-1815).

Walbach, a German-born career soldier who had fought with the French and Prussian armies before coming to America in 1798, was definitely the kind of experienced military man that the young United States needed. He was certainly valued by his new nation, as he would remain in the US Army until his death, at age 90 (there was no mandatory retirement age in the US Army prior to the US Civil War), in 1857.

Portsmouth, by now a hugely important American port and shipbuilding community, was blockaded by the Royal Navy (along with most of the rest of the US coast) during the War of 1812. Colonel Walbach had been appointed as second in command of all New England's seacoast defenses, and he feared that the dastardly British would take advantage of a landward blind spot of his beloved Fort Constitution, and attack it thus.

|

Walbach Tower circa 1880, and today. |

|

In the summer of 1814, Walbach directed Portsmouth residents in the construction of a Martello Tower on a hill just to the west of Fort Constitution. This casemated tower, called (of course) Walbach Tower, was 58 feet in diameter, mounted a 32-pounder cannon on its roof and three 4-pounder guns in casemates, to defend Fort Constitution's landward approach.

While I have been critical of Martello Towers, as they existed in the age of the starfort yet are demonstrably not starforts, Walbach Tower certainly seems as though it would have been a daunting obstacle...at least before it started deteriorating into the sad pile that it is today. The relative ease, speediness and thriftiness of a Martello Tower's construction, at least compared to that of a starfort, makes the defensive tower concept understandable, if unpalatable. To me. I doubt anyone else cares about it one way or another. |

|

|

Quickly and poorly constructed with improper materials, Walbach Tower began the deterioration process early, so it's probably fortunate that the British never attacked, or probably even noticed it. The tower was further damaged in 1897 when two Endicott Period batteries were built on the same hill, and even further disassembled during the Second World War (1939-1945). Today it looks like a pile of not much of anything.

|

Despite his Martello abomination, Walbach was later permitted to serve at a bevy of America's other great starforts, including Fort Monroe, Fort McHenry, Fort Trumbull and Fort Pickens. Improvements made in the 1840's raised Fort Constitution's walls still higher, replaced wooden gun platforms with granite emplacements and added a new Hot Shot Furnace: The fort had originally been blessed with a shot furnace in the 1800-1809 building period, but the 1840's was the apex of American Hot Shot technological knowhow, so just about everybody got a new Hot Shot Furnace in the 1840's. Not tired of the words Hot, Shot and Furnace yet? Perhaps you might enjoy a visit to HotShotFurnace.com.

|

|

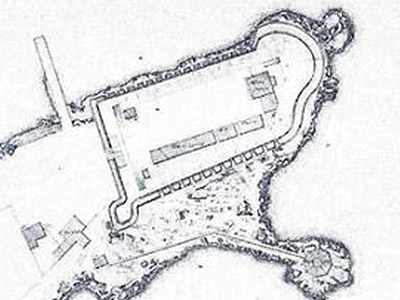

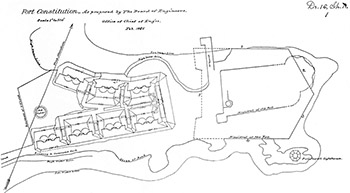

The US Army Corps of Engineers site plan of Fort Constitution, 1820. |

|

When the US Civil War (1861-1865) broke out, it caught a lot of folks unprepared to defend much of anything. Fort Constitution had been used as a training facility since 1852, but did have 25 guns mounted on its walls, a mix of 32-pounder cannon and 100-pounder Parrot Rifles. A 42-pounder naval gun was rushed to the fort, as well as some 150 troops, as surely the opening move of any war against the United States would involve an attack on Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Fortunately, there was no Confederate Militia in the vicinity to march in and take over the initially lightly-defended Fort Constitution, as had been the case with the Castillo de San Marcos in Florida and Fort Jackson in Louisiana.

|

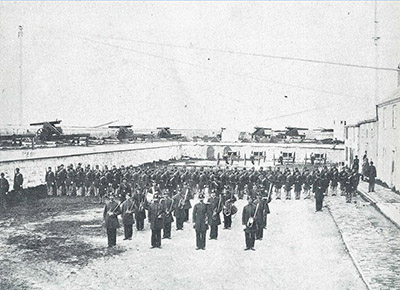

The interior of Fort Constitution in 1862, looking into the fort from just above and next to the main gate. Note that the river-facing wall is still intact! |

|

At the end of 1862, work commenced on a complete overhaul of Fort Constitution's defenses. A new three-story casemated granite monstrosity was planned to completely surround the fort's current walls. This would have been similar to Maine's Fort Popham, (click the link to see a pic), only three levels instead of Popham's two, and all the way around the original fort! This project only got as far as the destruction of the fort's original eastern wall, and a single level of granite wall with gun embrasures was built almost all the way along the fort's waterfront. The casemated upgrade was abandoned in 1867, it having become obvious during the war that masonry fortifications were no longer the impregnable bastions that they had once been. |

|

|

What was left after the abandonment of this project was a sad mess. Fort Constitution was placed into caretaker status, with a single Ordnance Sergeant left to watch the grass grow. In the early 1870's, there was a brief Congressional enthusiasm for upgrading America's aging coastal defenses. Plans were drawn up for a great number of projects for what would have been the Fourth System of American Seacoast Defense, but very few of these enterprises ever commenced, as very little money was ever assigned to them, and exactly zero of them were completed.

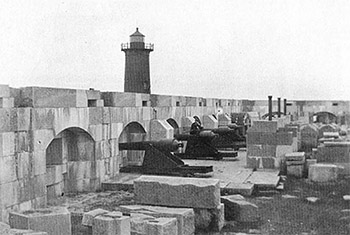

Fort Constitution's four 100-pounder Parrot Rifles, jammed into defensive mode in the fort's unfinished embrasures, circa 1880. These guns remained in place until at least 1903.

|

|

The US Army Board of Engineers' plan to build something altogether strange (yet eminently defensible!) next to Fort Constitution, mid-1870's |

|

In 1872, a fascinatingly weird, V-shaped, earth and concrete, 14-bay barbette gun battery was drawn up to enhance Fort Constitution's virtually nonexistent firepower. This would have been built on the hill to the fort's west, sharing the space with the crumbling Walbach Tower. Sadly, this spaceshiplike endeavor also did not come to pass.

|

Two batteries were finally built on that hill to Fort Constitution's west from 1897 to 1903: Battery Farnsworth, mounting two 8" disappearing guns, and Battery Hackleman, mounting two 3" guns for protecting Portsmouth's minefields. These were part of the Endicott Period of American seacoast defense improvements, when there was plenty of money floating around for such projects. Both of Battery Farnsworth's guns were shipped to Europe during the First World War (1914-1918), never to return. The Second World War (1939-1945) saw great emphasis placed on the management and protection of Portsmouth's minefields, and a concrete Mine Observation Station was built on Battery Farnsworth (which had just been sitting there unarmed, being unproductive), in 1943.

|

|

Some of the ruined riverside defenses of Fort Constitution in May of 2015, with the Mines Building, built in 1901, in the background. And my sister. |

|

Fort Constitution was declared surplus in 1948, and the 10-acre post was handed over to the US Coast Guard. Battery Hackleman was destroyed and replaced with a Coast Guard building. While the fort is open for visits, one must follow the blue line through the Coast Guard facility, lest one interrupt Coast Guard proceedings. I visited Fort Constitution in May of 2015 ( click here to see many pix and read of my visit), and found it to be in a poor state of repair. This is at least partially due to the unfinished state in which the Army left it in 1867, but mostly because of modern neglect. Take care of your precious historic locations, New Hampshire!!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|