|

Fort Carroll

Baltimore, Maryland, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1824 - 1857

Constructed by:

Robert E. Lee

Used by: United States of America

Conflicts in which it participated:

None

|

Of the cities amongst America's original thirteen colonies, Baltimore was a pretty big deal. 'Twas the third-largest city in the young United States until 1840, when the newly-Americanized New Orleans took the cherished Number Three crown. The Port of Baltimore was of vast importance to American trade, and hence, the city was blessed with what is arguably the starriest of all American Starforts, Fort McHenry, in 1806.

|

|

|

|

Inconveniently for Fort McHenry and all the other lovely starforts that had been built virtually on top of the cities they were intended to protect, the technology of artillery advanced by leaps and bounds in the 19th century. This made it necessary to situate one's defenses at a further remove from that which was in need of defendin', and caused those interested in keeping seaborne nasties away from Baltimore to cast an eye further down the Patapsco River, which waterway connects the city to the Chesapeake Bay, the Atlantic Ocean and, ultimately, the Sea of Okhotsk. It's difficult to find a person more important to the cause of American starforts than Joseph G. Totten (1788-1864). Appointed Chief of Engineers in 1838, Totten repeatedly urged that a new fortification be constructed on Sollers' Point Flats, a useful incidence of shallow water in the middle of the Patapsco River, pleasingly located almost equidistant from the city and the mouth of the river, where it meets the Chesapeake Bay. Congress finally got around to acquiring jurisdiction over Sollers' Point Flats from the Maryland legislature in 1845, and a US Army Engineer by the name of Major Cornelius A. Ogden began preliminary work at the location in 1848.

|

Fort Carroll in May of 2014, taken whilst motoring in a most motorious fashion o'er the Francis Scott Key Bridge. Fort Carroll in May of 2014, taken whilst motoring in a most motorious fashion o'er the Francis Scott Key Bridge. |

|

As originally designed, the Fort at Sollers' Point Flats was to be a fearsome three- (or maybe four-) tiered hexagon, mounting 225 guns. Many of the American coastal forts whose construction was initiated in this period were intended to be multi-tiered affairs, but finances, Congressional mamby-pambyness and ultimately the approach of the US Civil War (1861-1865) left the vast majority of these many-tiered monstrosities with only an embarassing one or two tiers upon their completion: Fort Richmond and Castle Williams in New York City, and Fort Point in San Francisco were the only three American forts to reach their originally-imagined multi-tiered ideal. |

|

Assigned to take over the fortification effort on Sollers' Point Flats in 1848 was US Army Major Robert E. Lee (1807-1870). Later to lead the Confederacy's Army of Northern Virginia to its Inevitable Yet Glorious Defeat in the US Civil War (1861-1865), upon his arrival in Baltimore on November 15, 1848, Lee was an able and respected engineer. He had laid the groundwork for the construction of Fort Pulaski in Savannah and Fort Wool in Hampton Roads, Virginia...and if all of that isn't enough of a starfort pedigree for you, Lee had also been stationed at the daddy of all American starforts, Fort Monroe, for several years.

|

Robert E. was in charge of the Fort at Sollers' Point Flats for the next three years and five months, but Congress' standard miserly distribution of funds for military purposes made work on the fort possible only in fits and starts. When our Major was without funds to work on his present assignment he was kept busy, traveling to Florida to investigate sites for future fortification; Boston to meet with the Board of Fortifications and Newport, Rhode Island, to plan additions to Fort Adams. When it was possible to get any work done on Fort Carroll, nothing came easy. |

|

Fort Carroll from the southeast, with the majestic Francis Scott Key Bridge serving as the backdrop. As always, all hail Google Earth. Fort Carroll from the southeast, with the majestic Francis Scott Key Bridge serving as the backdrop. As always, all hail Google Earth. |

|

Ground solid enough to support a fortification was found to be 45 feet below low tide, and many piles needed to be driven to that depth for a foundation. Lee contracted what was "probably" malaria in July of 1849 whilst overseeing work at the site, and had to recuperate for some months at his home in Arlington, Virginia.

Charles Carroll (1737-1832), a native Marylander, was possibly the richest man in America prior to the Revolutionary War (1775-1783). More importantly from an historical perspective, he had also signed the United States' Declaration of Independence, was the only Catholic to have signed that document, and was Maryland's first Senator following independence.

|

Fort Carroll as seen from Fort Armistead to its immediate southwest, and from Fort Smallwood to its south, in August of 2021. Fort Carroll as seen from Fort Armistead to its immediate southwest, and from Fort Smallwood to its south, in August of 2021. |

|

Life expectancy for a male in America was only in the mid-30's in the 1830's, but Carroll hung on until he was 95...surely this feat alone would have made him eligible to have a fort named after him! When Carroll finally shuffled off this mortal coil, he was the last surviving Declaration signer. Accordingly, the Fort at Sollers' Point Flats, which everyone will recognize as an unwieldy name for an American fortification (although the Spanish would have loved it, especially if you added a saint: El Fuerte más Regal de Puntos de Sólers Pisos de San Ignacio, for example, has a nice ring to it), was renamed Fort Carroll on October 18, 1850.

Lee's efforts at Fort Carroll would prove to be the last engineering work he did for the United States, as in May of 1852 he was ordered to West Point, where he was to take over as Superintendent. Today known as the US Army's primary academy, when West Point was established in 1802, its first mission had been to instruct in the art military engineering. |

|

America's early 19th-century starforts had been designed by gifted Frenchmen such as Charles l'Enfant and Simon Bernard, which was fine as far as it went, but President Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) understood that, in matters of strategic import, it was unwise to be too dependant on the good will of other nations. When Lee (unwillingly) left the Fort Carroll project in the hands of the man he had replaced as Superintendent of West Point, Captain Henry Brewerton (1801-1879), all that was needed to complete the fort was the money to supply building materials: The fort's foundations, wharves and all other supporting structures were in place, and its walls were already six feet high. It is the suggestion of Douglas Southall Freeman (1886-1853), author of the exhaustive, four-volume R.E. Lee: A Biography, that Lee's experience with Fort Carroll had been so grueling that "...this experience with the slow and troublesome construction of stone forts of the old type unconsciously operated to make him still more an advocate of earthworks." The US Civil War (1861-1865) was certainly all about the earthworks...though a few pre-existing starforts played a role in the conflict (mostly in the form of being effortlessly captured by the south's state militias at the outset of the war, and then being unexpectedly pounded to pieces by long-range Federal guns). For the most part, however, it was a war of movement, and nobody had time for much of anything more substantial than earthworks in the short term.

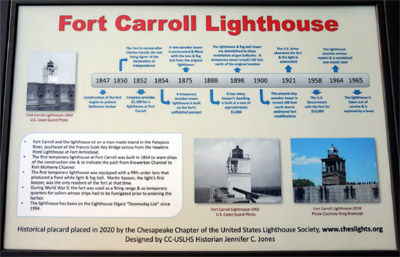

In 1854 a lighthouse was first erected on the fort's western wall, for which purpose Congress had provided $1,500 in 1852. Ultimately Fort Carroll's series of lighthouses would prove to be its only lasting contribution to Baltimore, though keeping a lighthouse up and running atop our fort was a constant struggle: Various forms of "temporary" lighthouses were banged together, which tended to not last very long, but which were nonetheless appreciated by riverfarers. Four lighthouses were built at Fort Carroll, until that light was replaced by a buoy in 1965...and honestly, for all the good it did Baltimore, Fort Carroll probably could have been replaced by a buoy a century earlier. |

|

Everything you might wish to know about Fort Carroll's series of ill-fated lighthouses, from a sign at Fort Smallwood, on the western bank of the Patapsco. Everything you might wish to know about Fort Carroll's series of ill-fated lighthouses, from a sign at Fort Smallwood, on the western bank of the Patapsco. |

Rewind, Captain Brewerton finally put the finishing touches on Fort Carroll (more or less) in 1857. The usual pattern of events upon the completion of a major American fortification was, absent an obvious, immediate threat, a gun or two would be mounted for form's sake, but the major investment of fully arming said fort didn't seem necessary. This was likely the case with Fort Carroll, though with the secession of eleven southern states from the Union at the beginning of 1861 and subsequent declaration of war, an immediate threat was belatedly perceived, and around 30 guns were mounted at Fort Carroll to defend Baltimore from the inevitable amphibious landing by the Confederate Navy. Maryland was a slave state at the outset of this conflict, and Baltimore likely would have stood with the Confederacy had the Federal Government not swiftly and wisely occupied it. Unlikely to be called into duty to defend the city (and more likely to need to defend itself from the city), Fort McHenry was utilized as a handy, secure facility in which to imprison those with a sympathy for the southern cause, including such dodgy characters as both the Mayor and Police Commissioner of Baltimore and Frank Key Howard (1826-1872), grandson of Francis Scott Key (1779-1843), whose poem about the British bombardment of Fort McHenry in 1814 became the United States' national anthem. Absolutely lock that guy up! These prisoners were forced to skootch over some to make room for all of Fort Carroll's powder and shot in 1864, when torrential rains flooded our poor, beleaguered fort's magazines, and everything that was needed to make its guns go bang was sent to Fort McHenry. Had Frank Key Howard (who had been arrested for writing an editorial in Baltimore's Daily Exchange that was critical of US President Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865)'s suspension of habeas corpus in Maryland, which made it possible for the government to imprison whomsoever it pleased without charge) been able to escape and deliver the news of Fort Carroll's sudden impotency to Richmond, surely Baltimore would have been immediately captured and we'd all be speaking with a southern accent right now*. |

As was the case with most of America's coastal fortifications, everybody lost interest in Fort Carroll following the war, and it was placed into caretaker status, which is what the army calls having one guy stationed there, keeping an eye on things. Our caretaker got company in 1888, when a two-story lighthouse keepers' dwelling was built in the fort. I bet those two guys played lots of cards!

The last quarter of the 19th century were dark days for America's coastal fortifications. Everyone had had plenty of anything to do with war, thank you very much, and the Civil War had exposed some major deficiencies in the United States' expensive masonry fortification system, not the least of which was their vulnerability to modern guns. And just when things looked the blackest, whom should come riding to the rescue, saving American starforts from certain demolition and historical obscurity but...the Spanish.

|

|

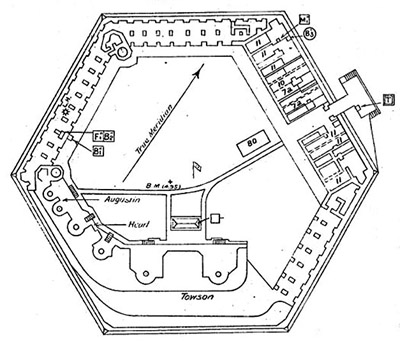

From a secret 1921 plan of Fort Carroll, featuring its Endicott Batteries. Click on it to see the whole plan, after which I'll have to ask you to turn yourself in to the authorities of a neutral nation, where you will be interned until the cessation of hostilities. Thx to FortWiki.com for the image! From a secret 1921 plan of Fort Carroll, featuring its Endicott Batteries. Click on it to see the whole plan, after which I'll have to ask you to turn yourself in to the authorities of a neutral nation, where you will be interned until the cessation of hostilities. Thx to FortWiki.com for the image! |

|

Newly interested in expanding into the murky waters of empire, the United States found itself at odds with Spain in such far-flung places as the Philippines and Cuba. These were peoples whom the Spanish had ruled and exploited for centuries, but it was universally agreed (by Americans) that the 20th century would be an American century, and woe betide the Spaniard who stood (or floated) betwixt America and her destiny. Which was also to rule and exploit folks in far-flung places, only in a more modern fashion...and taking things away from Spain in the western hemisphere meant reckoning with its navy.

Which turned out to not be much of a navy in modern terms, but fortunately it appeared frightening enough to William Crowninshield Endicott (1826-1900). Endicott was President Grover Cleveland (1837-1908)'s Secretary of War, and upon the realization that Europe's navies could pound upon America's shores with impunity thanks to the deteriorated state of the US' defenses, he convened and chaired the Board of Fortifications in 1885. This august group of gentlemen eventually recommended the construction of new fortifications at 29 points along the US coasts, at the staggering cost of $127 million, which would be approximately $∞ in today's dollars.

|

A more or less standard Endicott Battery, completed in 1891: Battery Decatur, at Fort Washington, on the Potomac just south of Washington, DC. What does Battery Decatur have to do with Fort Carroll? Nothing, I'm just trying to illustrate the Endicott Period in one image here, please use your imagination. A more or less standard Endicott Battery, completed in 1891: Battery Decatur, at Fort Washington, on the Potomac just south of Washington, DC. What does Battery Decatur have to do with Fort Carroll? Nothing, I'm just trying to illustrate the Endicott Period in one image here, please use your imagination. |

|

While the improvements made during the Endicott Period were somewhat at odds with America's pre-existing constellation of starforts, many of the strategic points that needed defending at the end of the 19th century were the same as they had been at the beginning of the 19th century, so many an American starfort was the beneficiary of a brand-new hideous concrete gun battery or two! While this modernization process certainly uglified a number of lovely starforts, it also probably saved those starforts, by making them part of America's seacoast defense system into the 20th century. The upshot of this was, Fort Carroll was semi-dragged into the modern age with the addition of three Endicott Batteries, built from 1898 to 1900! |

|

Built along Fort Carroll's south-facing walls were the casemate-displacing Battery Towson, named for Nathan Towson of the US Army, who served in the War of 1812 and Mexican-American War, mounting two 12" rifles on barbette (fancy word for "sits fetchingly atop everything") carriages; Battery Heart, named for Major Jonathan Heart, 2nd US Infantry, who served in the Revolutionary War and was killed by injuns in Ohio in 1791, had two 5" rifles on balanced pillar mounts; and Battery Augustin, named for Second Lieutenant Joseph Augustin, jr., who died at the hands of the wicked Spanish in the Battle of San Juan, Cuba, in 1898, which sported a pair of 3" rifles on masking parapet mounts. Thanks to these upgrades to Fort Carroll, along with a series of new batteries on the shores of the Patapsco of which we will learn shortly, Baltimore felt pretty good about its chances against an erstwhile seaborne invader for the first couple of decades of the 20th century. Fort Carroll was not granted its own dedicated garrison during this period, but was manned by a detachment from Fort McHenry. The First World War (1914-1918) gave everyone another case of the invasion jitters, but once it became plain that the German Navy would not be sailing up the Patapsco or any other waterway in the western hemisphere, the United States felt compelled to remove the majority of the enormous gun tubes that it had so expensively and recently installed to guard its shores and...send them places. Many went to France, where they were dumped unceremoniously ashore, surely impressing all of Europe with America's ability to produce, and then discard, large expensive objects. Few if any of these guns ever made it to where they could be used for their intended purpose, unless the purpose for all of this had been to declaw virtually all of America's seacoast defenses. |

|

|

...but had Baltimore been declawed? Not really, because at the same time that Fort Carroll was receiving its Endicottian upgrade, three new entities were being constructed along the lower banks of the Patapsco: Fort Howard, Fort Smallwood and Fort Armistead, all of which bristled with the most modern armaments that end-of-the-19th-century America could devise. |

Of the three, Fort Howard is the closest thing to an actual "fort"...although it's more of a base than a fortification, which expanded from its initial 1897 mission of supporting six individual batteries with armament ranging from 3" rapid-fire guns to 12" mortars, to a sweeping, 62-acre base that was mostly utilized by the US Veterans' Administration during the Second World War (1939-1945). Fort Howard's VA Hospital is a particularly majestic (and slightly sinister-looking) structure, and there's plenty of officers' housing, a movie theater and loads of support structures still standing, if in a slightly dilapidated fashion, on the fort's mostly-inactive grounds. |

|

Battery Winchester, which mounted a single 12" disappearing gun, representing Fort Armistead, just to the southwest of Fort Carroll. Battery Winchester, which mounted a single 12" disappearing gun, representing Fort Armistead, just to the southwest of Fort Carroll. |

|

Fort Armistead was named for George Armistead (1780-1818), who as a Major commanded Baltimore's famed Fort McHenry when the British came a-callin' in September of 1814. Armistead's other starfort credentials? He served as an artillery officer at Fort Niagara at the mouth of the Niagara River in 1813, where he participated in the capture of Fort George... and he served a brief period as the commander of Fort Adams in Newport, Rhode Island after the War of 1812 (1812-1815). Ole George certainly deserved to have some important stuff named after him, and the Fort Armistead that was built from 1898 to 1900 on Hawkins Point, to Fort Carroll's immediate southwest, had four batteries with armament ranging from the ubiquitous 3" quick-firing guns to a 12" disappearing gun at Battery Winchester, which is the only of Fort Armistead's batteries to have survived into the 21st century.

|

The lovely vista available at what would become Fort Smallwood made it the perfect place to watch the rockets glaring redly o'er Fort McHenry in September of 1814, when the Royal Navy was shooting at it. The sign in the foreground tells the tale. The lovely vista available at what would become Fort Smallwood made it the perfect place to watch the rockets glaring redly o'er Fort McHenry in September of 1814, when the Royal Navy was shooting at it. The sign in the foreground tells the tale. |

|

Fort Smallwood was built from 1899 to 1900 on Rock Point, directly across the Patapsco from Fort Howard. Named for William Smallwood (1732-1792), a Revolutionary War General and later the fourth Governor of Maryland, this fort lives up to its name by being the smallest of Baltimore's modern defenses, with only two batteries: Battery Hartshorne, which mounted a pair of 6" disappearing rifles; and the no-longer-extant Battery Sykes, which mounted two 3" guns. The Endicott Period had provided well for the defense of Baltimore Harbor, but as we return to the First World War, we find that these later installations also lost virtually all of their guns to the same weird Federal compulsion that took them away from Fort Carroll. |

|

The Roundfort of Our Current Interest did manage to hang onto its pair of 3" guns mounted on Battery Augustin through the war, but in 1919 US Secretary of War Newton D. Baker (1871-1937) initiated what would become known as the 1920 Disarmament Program, whereby many of the guns that had been mounted for coastal defense at the end of the 19th century were declared obsolete. Around 120 batteries along America's coasts were affected by this program, including Battery Augustin...and thus Fort Carroll lost its last guns on May 26, 1920. The army abandoned Fort Carroll in 1921, taking whatever was left of value to Fort Howard. Any other abandoned US coastal fortification would have languished for several decades and then perhaps be made into a park, but Fort Carroll is unique in that it sits in the middle of an extremely busy waterway, with a major US city staring at it. Baltimore lawyer Benjamin N. Eisenberg was entranced by the location's commercial possibilities, and bought it for $10,000 in 1958. Eisenberg's dream was to build a casino within the walls of Fort Carroll, despite the fact that gambling was presently illegal in the state of Maryland. Sadly, convincing the state government otherwise proved to be impossible. Not to be deterred, Eisenberg then spruced the fort up and mounted some fake guns made of cement, hoping to make it a tourist destination: Nope. He next envisioned a 20-story hotel on the island, but one of the major stumbling blocks to all of Eisenberg's increasingly weird schemes (other schemes arrived at by persons other than the good Mr. Eisenberg: Prison ( Alcatraz, anyone?); Base of a Statue-of-Libertylike statue of founder of Maryland Cecil Calvert (1605-1675) ( Fort Wood vibes); Giant neon WELCOME TO BALTIMORE sign) was how difficult it would have been to transport interested parties to Fort Carroll.

|

Transportation to American island forts is by no means unusual: Fort Jefferson and Fort Massachusetts in the Gulf of Mexico both support a healthy industry of comfy boats delivering hundreds of visitors on a daily basis, as does the Chesapeake Bay's Fort Wool...but those forts are further from shore, and involve a leisurely (and pricey) cruise to their destination, while Fort Carroll is right there smack in the middle of the river, just a few hundred yards from where a visiting boat might embark...which would make getting there seem like an easier task, but while the docks at which one might arrive at Fort Carroll may have been substantial affairs when Robert E. Lee was utilizing them, decades of neglect have rendered them virtually unusable. And then there's the birds. Maryland's Chesapeake Critical Areas environmental laws are so very protective of waterfowl, and those protected waterfowl are so very fond of Fort Carroll, that it would be virtually impossible for any sort of meaningful development to take place there. Negotiations with the birds are ongoing, but it seems unlikely that they'll be willing to budge from their position that Fort Carroll belongs to them. By all indications, the heroically hapless Fort Carroll is fated to crumble to nothingness in full view of every single person in Baltimore. |

|

A couple of white-breasted cormorants at Fort Wool: Selfish bastards. A couple of white-breasted cormorants at Fort Wool: Selfish bastards. |

|

As of at least 2004, Fort Carroll was inaccessible to the casual visitor, even if that visitor, casual or painstakingly formal, arrived in his/her own waterborne conveyance. There is no bridge from the landing, and there is a sign: Private. Keep Off. Guard Dog. We are assured that there is no dog (such a dog would require someone to feed it, if absolutely nothing else), but good luck getting past all the birds! *Key had actually been moved to Fort Warren in Boston Harbor by 1864 (where nobody speaks with a southern accent), so he was unlikely to have been aware of Fort Carroll's rain-inspired woes.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|