|

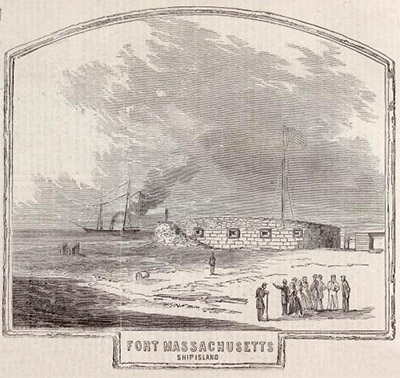

Fort Massachusetts

Ship Island, Gulfport, Mississippi, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1859-1866

Used by: USA, CSA

Conflict in which it participated:

US Civil War

Also known as: Fort Twiggs

|

A rare emojifort (think :D), Fort Massachusetts was weirdly named for the US Navy ship with which it had an inconclusive artillery duel on July 9, 1861. If this naming convention were more widespread, following the Battle of Jutland (May 31-June 1, 1916) the Royal Navy would be calling itself "the Imperial German Navy," and vice-versa.

French, British and Spanish flags all flew over Ship Island (although not simultaneously) before there even was a United States. |

|

|

|

French soldier and explorer Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville (1661-1706) was the first to chart Ship Island, on February 10, 1699. Pierre was starfort royalty in a sense, in that he was born in a starfort: Fort Ville-Marie, in what would become Montreal, Canada. D'Iberville used this island as a base from whence he "discovered" the mouth of the mighty Mississippi River shortly thereafter. In 1702 the island was named Ile aux Vaisseaux, "Island of Ship" (or maybe "Ship Island"). As a protected deepwater anchorage located betwixt Mobile Bay and the Mississippi River, Ship Island served as the main port of entry into the French Louisiana colony from Europe. When colonists arrived on the island in a deceased manner (which can't have been terribly unusual), they were pitched into a handy furnace for disposal. |

Fort Massachusetts: A stumpy, multi-toned wonder. Fort Massachusetts: A stumpy, multi-toned wonder. |

|

The city of New Orleans was founded in 1718, and rapidly became the main draw for French colonists in the region. Ship Island remained a useful stop at which to weed out the diseased and/or dead folks who showed up to colonize, and remained so until 1724.

The island became British property with the end of the Seven Years' War (1756-1763): The Treaty of Paris (1763) gave the Louisiana colony to Spain, but Great Britain gained the rest of French America. Yet another Treaty of Paris (1783), this one concluding the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), forced Britain to cede all the land from the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River to the new United States.

|

|

|

Though Ship Island technically lies betwixt the Appalachians and the Mississippi, it was somehow gained by Spain in this transaction. All told, there have been 31 Treaties of Paris, the first in 1229, the most recent in 1952. I have no further observations to make on this subject at this time.

At the behest of Napoleon (1769-1821), the French semi-secretly regained the Louisiana territory from Spain in 1800. Napoleon hoped to stretch his empire across the sea, but became convinced that this would be an impractical endeavor and sold the territory to the United States on December 20, 1803, for the cost of 38¢ (not really). It took the United States another seven years to find Ship Island, whereupon it was officially "claimed" by its new owner-nation in 1810.

|

The strategic nature of Ship Island was made painfully clear to the United States during the War of 1812 (1812-1815). In December of 1814, Admiral Alexander Cochrane (1758-1832) of the Royal Navy anchored his fleet of 50 warships with 8000 men betwixt Ship and Cat Islands (Cat Island being just a smidge to the west of Ship Island). The British used Ship Island as an embarkation point for their attack on New Orleans.

While the British were single-handedly prevented from capturing New Orleans by a sword-wielding future US President Andrew Jackson (1767-1845), Cochrane's ease of anchorage and other events of the War of 1812 illustrated a desperate need for loads of starforts to protect American shores. Ill-considered though it may have been, the War of 1812 was a definite boon for the art of American starfortery.

|

|

Well odds my bodkins, but Fort Massachusetts has its very own hot shot furnace! It is very unlikely that you are excited as I was upon making this discovery, but if you find such things interesting, perhaps I could gently direct you to Hotshotfurnace.com. |

|

Following the war, a Board of Engineers for Fortifications was appointed by President James Madison (1751-1836). This group toured the coastlines of the United States and by 1821 had recommended 50 sites that were in immediate need of fortification. A second round of recommendations increased the number of sites to over 200. One of these was Ship Island, which was declared a US Military Reservation in 1847.

American scallawags, in what would become a nearly annual activity, made plans to invade Cuba in 1849. Why did they want to invade Cuba? I'm sure they had important reasons, but mostly because it was there. The US Navy, catching wind of this tomfoolery, anchored off of Ship Island to prevent these potential invadists from using the island as a staging area for their attack. Cuba would remain a Spanish possession until the United States magnanimously (no self-interest whatsoever!) granted the island its freedom following the Spanish-American War (1898).

|

Congress finally authorized the construction of a fort on Ship Island in 1856, and work got underway in June of 1859. Construction proceeded under the auspices of the US Army Corps of Engineers, but most of the work was done by local civilian carpenters, stonemasons and blacksmiths. On New Years' Day of 1861, the unfinished, as-yet unnamed fort's walls towered a breathtaking six to eight feet above the sand of Ship Island.

On January 9 of 1861, Mississippi became the second state to secede from the Union. Mississippi militia bloodlessly took possession of Ship Island and the budding fort of our current interest shortly thereafter: The Corps of Engineers had wisely left the premises.

|

|

Lieutenant Samuel K. Thompson of Company C, 54th US Colored Troops with unidentified soldiers, posing with a 10" Rodman gun at Fort Massachusetts, sometime after the US Army had reclaimed the island. Thank you, Library of Congress! |

|

The militia who so heroically swooped down upon Ship Island were apparently unimpressed, because they soon swooped back to the mainland. Their initial goal seems to have been to render the fort inoperable for the boys in blue, as some small effort was made to burn the fort. The Confederacy then decided that it might be kind of nice to man a fort on Ship Island after all, and thus sent men dragging some form of artillery behind them back to the fort in June of 1861. They named their new fort, Fort Twiggs.

David E. Twiggs (1790-1862) held the distinction of being the oldest officer of the Confederate States Army. A native of Georgia, Twiggs served in the US Army during the War of 1812 and Mexican-American War (1846-1847). He was made the federal Commander of the Department of Texas and, when states began to secede from the Union in the runup to the US Civil War (1861-1865), turned all of Texas over to the Confederacy. "Hero!" bellowed the South, "Traitor!" bellowed the North. "What a terrible name for a starfort!" bellowed me. Fortunately, a new name was on its way, in the form of an iron-screw steamer built in Boston in 1860: The mighty USS Massachusetts.

|

The USS Massachusetts. Not the actual USS Massachusetts that played a part in the naming of this fort, as there seem to be no images available of that USS Massachusetts, but this is definitely a USS Massachusetts. This one was launched in 1896, designated BB-2, and saw action in the Spanish-American War (1898). Thanks again, Library of Congress! You are an awfully cool resource. The USS Massachusetts. Not the actual USS Massachusetts that played a part in the naming of this fort, as there seem to be no images available of that USS Massachusetts, but this is definitely a USS Massachusetts. This one was launched in 1896, designated BB-2, and saw action in the Spanish-American War (1898). Thanks again, Library of Congress! You are an awfully cool resource. |

|

The Massachusetts steamed within range of Fort Twiggs' guns on July 9, 1861. The resulting 20-minute artillery exchange betwixt ship and fort produced no notable injuries or damage to either side, and the ship departed once it had expended all of its ammunition.

Certain that they were about to be assaulted by the entire might of the US Navy, the Confederates of Fort Twiggs spent the next couple of months furiously strengthening the fort's walls with sandbags and timber...but then apparently decided something akin to "aaaah the hell with it," and abandoned the island in mid-September of 1861. Obviously still lurking nearby, the USS Massachusetts returned and took possession of Ship Island on September 17.

|

|

|

The US Army Corps of Engineers returned to Ship Island and got back to work on the fort. In 1862 troops stationed thereto started calling it Fort Massachusetts. Our fort was never officially named, and was only ever referred to as "the Fort on Ship Island" in official correspondence. Which is still better than "Fort Twiggs."

|

Ship Island was once again used as a springboard for an invasion of New Orleans, this time by the Union Army. Up to 18,000 northern soldiers were stationed on Ship Island during the attack's preparatory stages, in the Spring of 1862. On April 24, the US Navy laid waste to the formerly lovely Fort Jackson at Plaquemines Bend on the Mississippi River, leaving the road (by which I mean river) to New Orleans wide open. The city surrendered without a fight on May 1, 1862. The federal government continued to work on Fort Massachusetts until 1866 when, still incomplete, the fort was turned over to a "civilian fort keeper" by the name of C.H. "Pop" Stone. CFK C.H's job was to stay at the fort and "maintain its readiness." A series of army ordnance sergeants followed in Stone's footsteps as fortkeepers until 1903, when the fort's upkeep was turned over to Ship Island's lighthouse keeper...as though that guy didn't already have enough to do.

|

|

The January 4, 1862 issue of Harper's Weekly featured a lengthy article about Fort Massachusetts and Ship Island, illustrated illustratively by this illustration. Click on it to see the whole page! |

|

Ship Island was developed as a Quarantine Station in 1880, a function it served on and off until 1916. During the Second World War (1939-1945) the US Coast Guard used the island for an "anti-submarine beach patrol," watching for any German submarines so foolish as to surface within range of Fort Massachusetts' ridiculous 19th-century guns. The Army Air Corps also used the island's Quarantine Station as a recreation facility for its airmen during the war: Ooo, said the airmen, we get to relax at a Quarantine station!!

|

When work was started on Fort Massachusetts prior to the Civil War, bricks from Louisiana were used. Once Louisiana seceded from the Union on January 26, 1861, however, it was understandably apprehensive about supplying bricks to the federal government. After the Union had reclaimed the fort, work continued with redder bricks from Maine, which made a lengthy journey indeed. After the war, those Louisiana bricks were used once again. Thanks for the pic, Fortwiki.com! |

|

Fort Massachusetts' 20th century battle has been against the elements. In the best of times, all a fort built on a sand spit in the Gulf of Mexico has to contend with is corrosive salt air and the endless lapping of waves, but there are these things called "hurricanes" that regularly do major damage to everything in the region. A local "Save the Fort" campaign began in the 1960's, just in time for Hurricane Camille, whose tidal surge permanently split Ship Island in two in 1969.

One of the US Army Corps of Engineers' primary duties in the modern age is to keep the waterways of the United States clear of obstruction, which it accomplishes with an eternal dredging campaign. As the Corps dredges nearby shipping lanes, it blows the dredged sand towards Ship Island, helping to maintain the beach it needs to protect Fort Massachusetts from those wicked, toxic waves. This process is called "beach nourishment." Delicious!

|

|

|

Hurricane Katrina wiped out most of Fort Massachusetts' support structures (Ranger station, convenience store, snack bar etc.) in 2005, but many have been rebuilt...until the next hurricane. Today, Fort Massachusetts is reportedly in relatively great condition, and can be reached by private boat or National Park Service concession ferry.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|