|

Fort Meigs

Perrysburg, Ohio, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1813

Used by: United States

Conflict in which it participated:

War of 1812

|

In 1812, the United States declared war on Great Britain. The reasons for this were many, but one factor that made this a particularly desirable time for a new, wobbly nation such as the US to declare war on the most powerful country in the world was that the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) were presently occupying a great deal of Britain's time, treasure and troops...and the Brits would be forced to fight the US with at least one hand tied behind their back.

|

|

|

|

One of the reasons the United States wanted war was that it really wanted Canada. The American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) had more or less purged Britain from its original North American colonies, but north of the 49th parallel, the dudes in red coats still ruled the roost. Not for the first time, Americans eyed that border and erroneously imagined that all they would have to do was march northward for a bit and Canada would drop effortlessly into the star-spangled lap.

|

A sight that couldn't have been unusual for the men stationed at Fort Meigs during the War of 1812: Snow! The first siege took place at the end of April 1813, and my visit was on April 1 (not in 1813)...so there could have been snow in the vicinity at the time in question. A sight that couldn't have been unusual for the men stationed at Fort Meigs during the War of 1812: Snow! The first siege took place at the end of April 1813, and my visit was on April 1 (not in 1813)...so there could have been snow in the vicinity at the time in question. |

|

Another reason for the declaration of war was Indians. Though defeated in the previous war and expunged from the land, the British hadn't been expunged far enough, and from Canada they continued to supply Native Americans with arms and plenty of encouragement to kill Americans. By no means were all Indians hostile to Americans: There were hundreds of distinct tribes, each with their own identities and motives. Those that did choose to fight for the interests of Great Britain, however, represented an existential threat to the young United States.

At particular issue, thus, was the US/Canadian border...and, in the eyes of US General William Henry Harrison (1773-1841), that border's need of fortification. |

|

Harrison was made commanding general of the US Army in September of 1812, and swiftly identified a defensible spot on a bluff overlooking the Maumee River, about a mile and a half downstream from the remains of a British fort, Fort Miamis (of which little remains today). Here, Harrison decreed that a fort would be built, so that he and his troops could hunker down until enough reinforcements arrived to take on the British and Injuns across the river. Work began in February of 1813, and the fort was named for Ohio's Governor, Return J. Meigs, Jr. (1764-1825), in thanks for the Governor's support of Harrison's efforts, which came in the form of militia and supplies. The British and their Indian allies were polite enough to wait until Harrison & co. completed Fort Meigs in April before they approached with ill intent. |

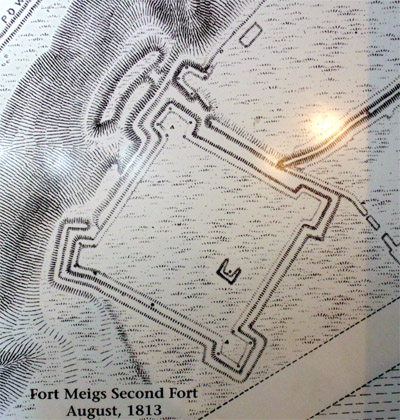

A really cool graphic in one of Fort Meigs' blockhouses, which shows all of the forts, star- and otherwise, that graced the area: Fort Miamis, Fort Defiance, Fort Harmar, Fort Malden and Fort Meigs. If you squint really hard at the Fort Meigs drawing, you'll note an actual starfort shape at the fort's lower left: This was the second version of Fort Meigs, of which we'll learn later on this page. |

|

Those more observant amongst us will have noticed that Fort Meigs is in absolutely no way a starfort, but a stockade fort. I would argue that a stockade fort utilizes two of the major attributes that make a starfort a starfort, which are strongpoints (blockhouses in this case, bastions in a true starfort) with curtain walls betwixt them (log palisades here, as opposed to masonry walls). But I wouldn't argue too strenuously, because I'm not trying to convince anybody that this is a starfort.

Fort Meigs consisted of seven blockhouses which, had this been a Spanish fort, would have been named things like like Her Most Holiest Mother of Jesus, Mary the Magnificent Blockhouse, but in terse Yankee style, they were just referred to as numbers one through seven. Five batteries were strategically placed along the walls, named Grand Battery, Little Battery, Croghan's Battery, Woods' Battery and Huckel's Battery. Eight gates provided plenty of places to enter or from which to sally forth, and two powder magazines, a well and a series of 14-foot-high traverses, essentially earthen berms for separation betwixt the batteries, filled the fort's interior which, at just over 62 acres, was the largest stockade fort in North America. At the time of the forthcoming events, 1,200 Army regulars and militiamen manned Fort Meigs.

|

|

|

At the end of April, 1813, a British force of 1,000 under Major General Henry Proctor (or perhaps Procter)(1763-1822), having descended from Fort Malden at Amherstburg, close to Detroit, set up camp at the ruins of Fort Miamis.

With the British was a 1250-man Indian force led by Shawnee warrior chief Tecumseh (1768-1813), who had convinced Indians from several different tribes to fight for his dream of an independent Indian nation east of the Mississippi River, which would be under the protection of the British. Whether or not the British ever intended to actively support such an endeavor is anybody's guess, but it certainly would have kept the dastardly Americans off-balance were it to have ever transpired. Regardless, the Tecumseh Confederacy, as it was known, served as effective, if frequently difficult to control, allies for the British in the War of 1812. |

|

|

While the Americans were outnumbered two to one by their besiegers, that's the whole point of a fort now isn't it, and they withstood four days of bombardment. On May 4 reinforcements arrived, to the tune of an additional 1,600 Kentucky militiamen. The following morning, 866 Kentuckians paddled their way across the river, attacked the British gun batteries and chased the gunners and Indians into the woods.

Now, anyone who's ever watched a movie in which Indians are the bad guys knows that one does not pursue Indians into the woods, no matter how excited and certain of victory one is. Sadly, Fort Meigs' movie projector was apparently an early casualty of the British bombardment, and off into that Indian-infested forest scampered the Kentuckians, with predictable results.

|

|

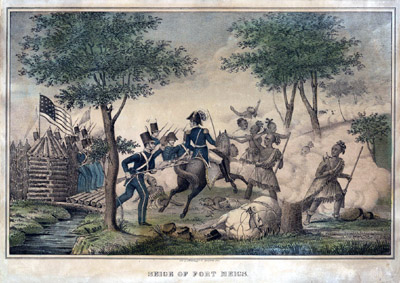

Seige [sic] of Fort Meigs by DW Kellogg & Co., 1845, in which future US President William Henry Harrison leads his magnificently shakoed and very tidy troops on a sally to smite the wickedly beskirted Indians. Seige [sic] of Fort Meigs by DW Kellogg & Co., 1845, in which future US President William Henry Harrison leads his magnificently shakoed and very tidy troops on a sally to smite the wickedly beskirted Indians. |

|

Of the 866 Kentuckians that went after Tecumseh's warriors, only about 150 made it back to Fort Meigs. While the British and Indians withdrew on May 9, leaving Fort Meigs untaken, this was a truly dreadful defeat for the American militia.

The British would have been happy to leave Fort Meigs alone at this point, but their Indian allies were insistant: The (American) white man fort must fall. When they returned for a second try in July of 1813, the attackers did not announce their arrival with an artillery barrage, but with subterfuge! The Indians yipped and howled most convincingly off in the distance, as though a battle were taking place near the fort. The expectation was that the idiot Americans would mindlessly charge back into the woods in search of this enticing battle, whereupon they would be ambushed and slaughtered. And though Americans were very good at being ambushed and slaughtered whenever Indians were their adversaries, for some reason they stayed safe in their fort on this occasion.

|

|

Out of ideas, the British and Indians gave up and headed southeast to attack Fort Stevenson at what is today Fremont, Ohio. This did not go well for the men in red coats and/or loincloths: The British lost so many men that they were forced to retreat to Canada, and Tecumseh was killed at the Battle of the Thames in October of 1813 (the man who was credited with killing the notorious Indian chief, Colonel Richard Johnson (1780-1850), rode his fame all the way to the Vice Presidency in the Martin Van Buren (1782-1862) administration: Johnson's supporters in the 1840 election chanted the memorable and confoundingly ridiculous slogan, Rumpsey Dumpsey, Rumpsey Dumpsey, Colonel Johnson killed Tecumseh, and one imagines that "Tecumseh" rhymed with "dumpsey," otherwise this slogan would make even less sense than it already does).

Once Tecumseh was gone, so was the pan-tribal confederacy of Indians that had been their only hope of regaining territories lost to white person expansion.

|

|

The second iteration of Fort Meigs, which was truncated due to less expectation of a need to defend it from anybody. Ironically, once they didn't need to defend it any more, they made a starfort! The second iteration of Fort Meigs, which was truncated due to less expectation of a need to defend it from anybody. Ironically, once they didn't need to defend it any more, they made a starfort! |

|

Once it was clear that the British and Indians were no longer a threat in this region, Fort Meigs was downgraded to a supply depot, which required a smaller footprint and much smaller garrison. With 100 militiamen left behind to guard their new starfort-shaped supply depot, the rest of Fort Meigs' garrison marched north to Canada, which they proceeded to not capture.

|

After the war, the new & improved & smallerfied Fort Meigs was abandoned by the army, and some years later what was left of it burned to the ground "under mysterious circumstances" (the pyrotechnic ghost of Tecumseh?). A stately obelisk was erected by the state of Ohio at the fort's location in 1908, in recognition of the services of the gallant men who defended their country on this spot.

The United States' Bicentennial in 1976 sparked a lot of interest in American history, and was the prompting influence of a good amount of historic fort reconstruction. Fort Meigs was duly reconstructed in the 1970's and opened to the public: It was refurbished in the early 2000's, and today stands as a most impressive artifact of the War of 1812, which event is generally overshadowed by its more famous cousins, the Revolutionary and Civil Wars.

Croghan's Battery, which faces the Maumee River and which, I think we'd all have to agree, is a pretty dinky battery.

|

|

Before Fort Meigs was reconstructed in the 1970's, this monument, which was erected in 1908, was the only indication that there had been a cool fort there. Click here to see the plaque on one side that honors William Henry Harrison. Note the exquisitely threatening sky behind the monument: A murderous snowstorm was stalking me during my visit there! Before Fort Meigs was reconstructed in the 1970's, this monument, which was erected in 1908, was the only indication that there had been a cool fort there. Click here to see the plaque on one side that honors William Henry Harrison. Note the exquisitely threatening sky behind the monument: A murderous snowstorm was stalking me during my visit there! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|