|

Click on any of the markers for a starfort's name and link to its page or representative image.

|

|

|

|

|  |

|

Among those territories the British had agreed to vacate with all convenient speed were five forts in the Great Lakes region and two at the northern end of Lake Champlain, of varying size and relative starrishness, all of which were clearly in American territory...and the one thing that the British military did not do was vacate them, at any speed whatsoever. Additionally, Great Britain built another fort in American territory, eleven years after the Treaty of Paris was signed.

Why were the British so recalcitrant on this issue? They justified their actions by citing the instability in the region after the end of the war, and also claimed that the US government had failed to live up to their agreement to compensate loyalists for British losses...but one suspects that they never intended to give up those forts until absolutely forced to do so, and/or the best intentions of the British government in London didn't filter all the way down to soldiers manning forts nearly 4,000 miles away. Whatever, a decade after agreeing to vacate these forts, the British had not done so.

|

|

|

|

|

The first page of the Jay Treaty The first page of the Jay Treaty

|

While defeat in the American Revolution was no kind of positive development for Great Britain, they did find themselves in an advantageous commercial position after the war: As a major trading partner of the new nation, England was still reaping the benefits of American enterprise without having to physically (and expensively) maintain it with a military presence.

Eternally displeased with anything good happening for Great Britain was France, which nation began consuming itself in dreadful violence in 1789, in the process that began with the French Revolution and concluded with Napoleon trying to conquer all time, space and dimension. France had of course played a role in America's independence, and there was a very real possibility that the two "Revolutionary" nations would join to fight against poor defenseless little Britain. London, therefore, had plenty of reasons to make nice with its former colonists across the pond.

And there were issues that indisputably needed addressing. American seamen were being pressed (forced into naval servitude) by the Royal Navy at a steady clip; American commercial ships were being confiscated by that same rapacious Royal Navy, much of the US/Canadian border was legally indistinct, the British were providing arms and inspiration for Indians to fight against American interests in the Northwest, and we all know about the forts that were being held against their American will. |

|

|  |

|

Officially and long-windedly known as the Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation, Between His Britannic Majesty and The United States of America, the treaty was negotiated by John Jay (1745-1829), a genuine American Founding Father who had signed the Declaration of Independence and negotiated the Treaty of Paris with Great Britain in 1783, which had ended the Revolutionary War. The Jay Treaty was signed on November 19, 1794 and went into effect on February 29, 1796. Shortly after the Jay Treaty was wrapped up, its namesake became Governor of New York, and even had a starfort named after him: The lovely four-bastioned Fort Jay was initiated in 1794, and guarded New York Harbor from the notionally inevitable onslaught of the Royal Navy. Did the Jay treaty work? Yes! And absolutely not. Great Britain did immediately vacate the eight forts in question, but the Royal Navy continued to heap indignities upon seafaring Americans, and the impressment issue in particular would be one of the most loudly-bellowed reasons the United States would declare war on England in 1812. But this was no fault of the treaty that brought the following eight forts back into the American fold. |

|

|

|

Lake Champlain, which represents the borders of New York, Vermont and Quebec, received a lot of fortified attention during the French & Indian War and American Revolution. Fort Montgomery guards the lake's northern extent and Fort Ticonderoga sits 100 miles away at its southern end, and there are plenty of other examples of the art of fortification between. The British built White House, a solid two-story, white stone structure to safely house a garrison, at Point au Fer in 1774. This was about a mile south of Rouses' Point, where Fort Montgomery would later be built. American troops managed to wrest this sturdy endeavor from the British in May of 1775, and American General John Sullivan (1740-1795) wisely directed that White House be further fortified in June of 1776. An entrenchment was dug around the house in the inner starry pattern we see today, and a 12-foot-high wooden stockade, backed with cannon, was added. |

|

|

|

The Battle of Valcour Island took place in October of 1776: The first outing of the new US Navy, which it lost...but it did so in a most heroic fashion, delaying the British in their aim to invade the Hudson River Valley. Heroic or not, the Americans lost control of Point au Fer, and the newly-starrified White House was reoccupied by the British.

|

|

|

|

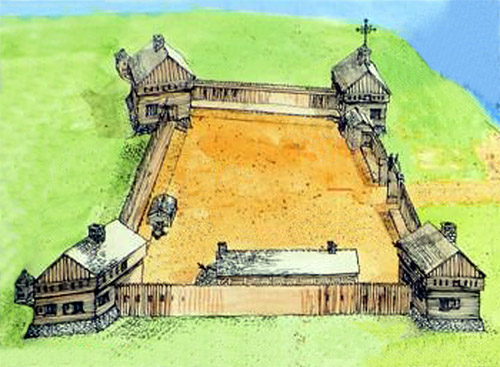

Following their defeat in the war, the British remained at what was by now referred to as Fort au Fer, and over the next 20 years enhanced it into the pugnacious state represented in the above image. From this fort they patrolled Lake Champlain in the gunboat Maria, which behavior is even more aggressive than just sitting in a fort you agreed to leave for two decades with your arms folded in defiance.

Once the Jay Treaty finally evicted the obstinate British garrison from Fort au Fer in 1796, American troops may or may not have had time to occupy it before a person described as a "French refugee" maliciously lit the fort aflame, which completely destroyed it. American troops did come and camp amongst the fort's remains during the War of 1812, where they kept an eye peeled for British naval activities. |

|

Beginning in 1809 parcels of the land on which Fort au Fer stood were sold to private individuals. In 1870 a Richard Scales built a home, whose basement was made of stonework from the ex-fort. That house reportedly still stands, but I don't know for certain which house it is, so I choose not to attempt to show it to you! Other than those stones in that dude's basement, no trace of Fort au Fer remains today, though it is well-signed with historic markers.

|

|

|

|

|

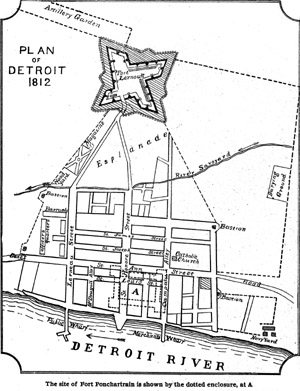

First, there was Fort Ponchartrain du Détroit. This was a stockade fort that was established in 1701 by the French on the northern bank of the Detroit (Détroit?) River, and soon a thriving community was sprouting up outside its walls.

The British took the fort in 1760 during the French and Indian War (1756-1763), removed the é as was their wont, and semi-renamed it Fort Detroit. |

|

Detroit was too far to the west to serve much of an active role in the American Revolutionary War, but it was still an important stop along the riverine superhighway of the day, serving as a supply depot for those Indians who wished to nobly assist the British war effort by attacking American interests, and/or American settlers.

|

|

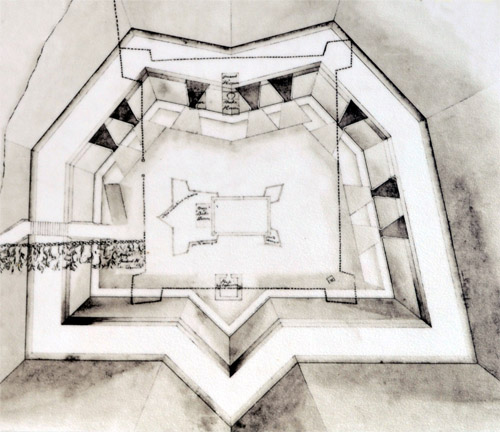

Dissatisfied with the size and shape of the original French fort at Detroit, British Captain Richard B. Lernoult initiated construction of a new starfort, just a few hundred yards to the north of the old, at the end of 1788.

The new Fort Lernoult was a much more impressive edifice than had been that French fort with the é in it, and it soon supplanted the original fort's importance and influence...so much that Fort Lernoult was frequently referred to as Fort Detroit.

As those of us who have been reading this page know, the British did not decamp and vamoose from Fort Lernoult upon the conclusion of the Revolutionary War, but they did once that pistol-packin', all-American, rootin'-tootin' badass John Jay told 'em to, in 1796. Of course all the British did was move about 2500 feet across the Detroit River to Fort Malden at Amherstburg, but at least they were out of American territory.

In 1805 a fire razed all of Detroit, leaving only two structures intact: Fort Lernoult was one of 'em. One would suspect that the responsible party for this conflagration would have to have been the "French refugee" who torched Fort au Fer, which fire also occurred in 1805, but since a starfort was just about the only thing not burned down in the Detroit fire, perhaps it was an Italian refugee. |

|

|

|

The British returned to Detroit early in the War of 1812 (1812-1815), whereupon the city, and Fort Lernault, were willingly handed over without a fight. The Americans regained fort and city later in 1813, and in order to discourage any future capture, the fort was renamed Fort Shelby, after Isaac Shelby (1750-1826), who as governor of Kentucky provided many of the troops that made Detroit's recapture possible. Renaming the fort did the trick: Nothing else happened there. Fort Shelby/Lernoult/Detroit was garrisoned until 1826, at which time it was handed over to the city of Detroit, who couldn't come up with a single reason why it needed to be there, and thus had it razed. Detroit was still maddeningly close to British-owned Canada, however, and by 1840 it became apparent that perhaps the destruction of Fort Shelby had been a smidge premature. Construction of a proper masonry starfort, Fort Wayne, began in 1843. Today Fort Wayne is still where they put it, but the only hints that there was once a Fort Lernoult in what is now downtown Detroit are a couple of plaques bolted to a couple of buildings, one of which (markers) can be viewed here. |

|

|

The term "fort" has always been somewhat nebulous. We at Starforts.com generally think of "forts" as nice big masonry starforts of course, but in reality forts came in all shapes, sizes and building materials. Case in point: The blockhouse! While a wooden blockhouse would have been no kind of obstacle for an artillery-armed force (or anyone who possessed the secret of fire), at the right time and place the diminutive blockhouse served its purpose, in many times and places.

So, was a blockhouse, standing bereft of any outer fortifications, a fort? In this case at least, the blockhouse that the British built on an island in the north of Lake Champlain in 1781 was known as the Fort at Dutchman's Point, or sometimes Loyal Block House, and occasionally Fort Loyal. |

|

|

|

A British spy ring, responsible for snooping about in Vermont, was based at Fort Loyal and run by a man named Justus Sherwood (1742-1826). A native of New York, Sherwood fought in the French and Indian War and decided he was a Loyalist for the Revolution. Loyalists were by no means rare in Vermont during the Revolutionary War: The Vermont Republic was established in 1777 as an independent entity, at least partially due to widespread Vermontian indecision as to which side to throw in with during the war, making Vermont a pretty good place to run a British spy ring!

Vermont finally gave in and became the 14th United State in 1791, but there was Fort Loyal, still occupied by the British, ten years after the end of the Revolutionary War. Nothing speaks to the tenuousness of the regional situation at the time more eloquently than the fact that the United States didn't have the means (or more likely the will) to do anything about this relatively puny British outpost on American soil.

Being by nature made of wood, Fort Loyal faded into nothingness after the British finally left in 1796, but a replica was built around 1953 by historian and author Oscar E. Bredenberg, which is the image we see above: I'm fairly certain that the screen door isn't historically accurate, but I bet it kept the skeeters out. Today there's nothing visible of this replica, at least from Google Maps, and there don't seem to be any more recent images of it either, which leads me to suspect that it's gone. Dutchman's Point, known today as Blockhouse Point, is now private property.

|

|

|

|

|

If you can stretch your imagination enough to consider Fort Mackinac a starfort, it is the second-furthest northern starfort in the United States! It was built in 1780 by the British to replace the more-difficult-to defend Fort Michilimackinac, which had been overrun by crafty, lacrosse-playing Indians and then occupied by French Canadians in 1763, during the French and Indian War.

The British finally departed Fort Mackinac in 1796, but returned and took it back in 1812, surprising the American troops who had no idea the War of 1812 had started without them. The fort was returned to American control at the conclusion of the war in 1815, and it remained more or less actively garrisoned until 1870. |

|

If it seems like I'm giving Fort Mackinac short shrift in the information department, that's because there's a whole page about it at this very site, where you can read all about Fort Mackinac in excruciating detail! And you may do so by clicking here! |

|

|

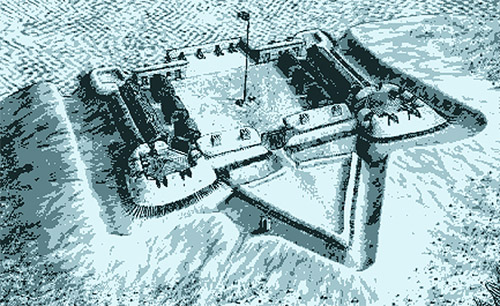

Fort Miamis is unique amongst the forts on this page in that it's the only one that the British built on American soil after the conclusion of the Revolutionary War. Eleven years after. A mere four months before the signing of the Jay Treaty, 200 British troops were settling into this brand-new earthwork fort on the Maumee River in Ohio...whose image to the right is an "artist's conception based loosely on descriptions of the fort." It's also unique in that, it's the only non-masonry fort on this list of which there are still visible remains.

Fort Miamis was built where and when it was due to the madcap adventures of the crazed and effective American General Mad Anthony Wayne (1745-1796). |

|

|

|

The Northwest Indian War (1785-1795) was raging, with the new United States determined to secure the Northwestern US from those Indian tribes who were being obstinate about surrendering and going away, which tribes were being armed and encouraged by the British. The Brits were convinced that Mad Anthony intended to storm up the Maumee River and nab Detroit, which at the time was still in British hands. As it happened, Mad Tony wasn't interested in Detroit yet, but Great Britain's newest fort in the New World served as a fortified Indian arms cache.

|

|

What's left of Fort Miamis today. What's left of Fort Miamis today. |

|

The British had absolutely no intertest in direct conflict with American troops, however. In August of 1794, following the Battle of Fallen Timbers, a gaggle of British-allied Indians who were being chased by Mad Anthony's troops asked to please be granted refuge within Fort Miamis. The British refused this request, and soon thereafter noted with dismay that American troops led by Mad Anthony himself had followed the Indians to Fort Miamis.

With his troops camped a mile away, Crazy Tony approached the fort alone and walked around it at pistol shot range, taunting its inhabitants. The British chose not to rise to his insults, deciding that discretion was the better part of blablabla. Their Indian allies, who had been watching this drama from the nearby woods, determined that it was pointless to stand against a man with such powerful hoodoo and departed. Ladies and gentlemen, I give you Mad. Anthony. Wayne. |

|

As we know the British left Fort Miamis in that magical fort-leavin' year of 1796, and it was soon abandoned by the Americans as well. Being earthen in nature and on a riverbank, it deteriorated swiftly.

|

|

The British returned to the banks of the Maumee during the War of 1812 with an interest in besieging Fort Meigs, a vast stockade fort that the Americans had built just a few miles down the river from the dilapidated Fort Miamis' location in 1813. While there wasn't much of Fort Miamis left, the British nonetheless used whatever was there as their base of operations for the campaign, which included running some 700 captured Kentuckians through a gauntlet in and around the fort's remains, which predictably resulted in several of them being killed. Shawnee leader Tecumseh (1768-1813) reportedly showed up and humanely put an end to this activity. The British move against Fort Meigs was unsuccessful, and by 1814 Fort Miamis had been abandoned for the last time. Local civic organizations bought some of the property upon which Fort Miamis sits in 1942, and in 1957 an historical marker was placed thereupon. |

|

Tecumseh nobly spares the lives of some wayward Kentuckians at Fort Miamis in 1813, in an 1860ish etching by John Emmins. Tecumseh nobly spares the lives of some wayward Kentuckians at Fort Miamis in 1813, in an 1860ish etching by John Emmins. |

|

Today, Fort Miamis Historic Site is nestled amongst peoples' homes in a residential area. There is an elementary school named for the fort, just five short blocks away. I wonder where they go for field trips?

|

|

|

|

|

Fort Niagara is arguably the most significant of the forts affected by the Jay Treaty. The French were the first to fortify here at the mouth of the Niagara River where it meets Lake Ontario, building the Maison a Machicoulis, "House of Peace," in 1726. The Indians had agreed to let them build at this spot, as long as it wasn't a masonry fort...which is precisely what it was, only in the shape of a big house. This location was of vast strategic import, and saw no end of squabble betwixt the French, British and Americans over the following century. When the British were finally squeezed out of Fort Niagara in 1796, they went right across the river and immediately built one of the many forts called Fort George, and when that fort was captured by the Americans in 1813, the Brits meandered a little further up the river and established Fort Mississauga. Say what you will about the British, but they were physically incapable of giving up. Anything. Anywhere. Ever. As you may have guessed, a starfort as desperately important as Fort Niagara does indeed have its own dedicated page at this site, which you can access by clicking here. |

|

|

Fort Ontario is certainly among the more significant starforts listed on this page, and is quite possibly the most beautiful and perfectly-formed starfort in North America (with apologies to the other most beautiful and perfectly-formed starfort in North America, which is Fort Morgan at Mobile Bay). The British first started building forts at the southeastern corner of Lake Ontario in 1755, which began a series of violent events that would result in no fewer than five iterations of Fort Ontario being built, destroyed and rebuilt up until 1870, when everybody just kind of gave up on fortifying things in the United States, until the Endicott Period got the American fortification ball happily rolling once again. 'Twas the third version of Fort Ontario that the British were forced to leave in 1796 by the Jay Treaty. There is of course a page dedicated to Fort Ontario at this site, which, should you have interest, is available by clicking here. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Fort that would become Oswegatchie was first established in the Spring of 1749, when the redoubtable Missionary Father François Picquet (1708-1781) led an expedition to the confluence of the Oswegatchie and St. Lawrence Rivers. The good Father named his mission fort Fort de la Présentation, after the Feast of the Presentation, which honors the Virgin Mary (18BC-sometime after 33AD). The French were permitted to build their fort by the Iroquois, who were looking to offset Britain's intent to build what would become Fort Ontario.

Picquet was a fightin' priest: He drew Indians from the region and encouraged them to go and attack the British. When the French and Indian War got cookin', Fort de la Présentation became more important to new France, and an actual military commander was put in charge of the fort, much to the Fightin' Father's chagrin. |

|

Father Piquet and troops based at la Présentation ranged far and wide during the war, coming up against the British and/or Americans at such stellar starforts as Fort William Henry and Fort Carillon, which of course was the earlier, incorrect name for the spectacular Fort Ticonderoga. The conclusion of the war brought with it near-complete British control of what had been New France...which included our presently-interesting fort with the completely non-British é in it. Only because the British were getting confused by all the forts they had already named after King George III (1738-1820) did they rename their new fort after one of its significant rivers, Fort Oswegatchie. |

|

Throughout the American Revolutionary War, the British utilized Fort Oswegatchie much as the French had in the previous war: By housing troops who were sent out to wreak havoc amongst the enemy. In June of 1779 our fort was attacked by a detachment from sort-of-nearby Fort Stanwix, prompting a retaliatory attack, which netted 29 prisoners and three scalps. Whose scalps? Unimportant. Just scalps. British troops left Fort Oswegatchie on June 1, 1796, as per the terms of the Jay Treaty. Americans didn't arrive there until August 11, in the form of settlers, not troops. The fort had been the basis of a fairly large city, with a population of over 3,000, mostly Iroquois Indians, in 1755 when Montréal boasted a population of 4,000. Americans renamed the town Ogdensburg, after Samuel Ogden (1746-1810), a prominent local landowner. The Indians were, perhaps unsurprisingly, expected to find lodgings elsewhere. American troops finally made it to what they called Fort Presentation at Ogdesnburg at the beginning of the War of 1812. Directly across the St. Lawrence River from Ogdensburg is the Canadian town of Prescott, where the British began building Fort Wellington in 1812. While a major river might seem like a major obstacle on a map, that particular river is frozen more or less solid, several months of the year. |

|

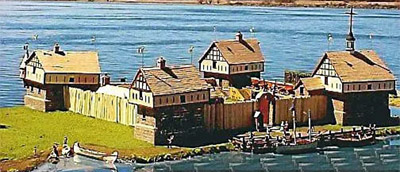

A model of Fort de la Presentation, and a painting of how it appeared in 1760. One assumed the battling ships would be a British one and a French one. A model of Fort de la Presentation, and a painting of how it appeared in 1760. One assumed the battling ships would be a British one and a French one. |

|

Various malicious frozen crossings occurred o'er the St. Lawrence betwixt these two forts over the course of the war, and in February of 1813 an American raid on the town of Brockville prompted the British to slide their way across to capture Ogdensburg once and for all. Fort Presentation didn't fare well in this action, and was abandoned shortly thereafter. Ogdensburg residents used the fort's crumbled bits to rebuild their town. Today there is a nice marker where the fort once stood, and the Fort de la Présentation Association hopes to build us a replica of the original. |

|

|

|

|

|

|