|

Fort Livingston

Grand Terre Island, Louisiana, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1841-1861

Used by: USA, CSA

Also known as: Fort Barataria,

Fort on Grand Terre Island

Conflict in which it participated:

US Civil War

|

At the beginning of the 19th century, New Orleans was important. A case could certainly be made that it's still important today, but not in the same way that it was when it first became an American city. La Nouvelle Orléans was founded in 1718, and was French, Spanish and then French again before Napoleon (1769-1821) sold New France to the infant United States in 1803. By 1840, New Orleans was America's third-largest city, thanks to its location at the southern extent of the Mississippi River and the shipping opportunities that arose from this. |

|

|

|

Europeans with ships naturally desired New Orleans for themselves, and in the early 19th century much of the United States' outlying territories at least appeared to still be up for grabs. The US' determination to hold on to New Orleans was illustrated by the constellation of starforts it built to protect the city: Fort Macomb, Fort Pike and Fort Jackson were all constructed between 1820 and 1840 to protect New Orleans from foreign incursion. Some European cities had wads of starforts protecting them ( Paris had sixteen, for all the good they did Paris), but three (+1, as we will soon discover) substantial starforts to defend an American city, all built within a relatively brief span of time, made it clear to all that, even though New Orleans was full of French-speaking persons, America considered it to be as American as New York. Or at least hugely financially beneficial, which amounts to the same thing. |

Grand Terre Island, looking like a delicious strip of bacon floating in space, with Fort Livingston at its southwest tip. I always cut the Fort Livingston off of my space bacon before frying, but to each his own. |

|

In the early years of the 19th century, Jean Lafitte (c.1780-c.1823) and his brother Pierre ran a lucrative piracy and smuggling business in New Orleans. Congress passed the Embargo Act of 1807, which outlawed any foreign trade for American citizens, and when the government finally got around to enforcing this in 1808, it put a major crimp in American businesses up and down the coast.

Being unconstrained by the need to do things legally, the Lafittes moved their operation to Grand Terre Island shortly thereafter. The islands of Grand and Grand Terre guard the opening to Barataria Bay directly to New Orleans' south. This location was perfect for the Lafittes because it was remote and offered a simple, covert means of getting to New Orleans, where they continued to ply their trade. |

|

|

For those exact same reasons, however, Grand Terre Island was a clear nominee for a starfort. When the War of 1812 (1812-1815) lumbered into being, Britain's Royal Navy reasonably stepped up patrols in the Gulf of Mexico, and in September of 1814 reached out to Jean Lafitte, requesting his assistance and offering him British citizenship and some property in British colonial settlements. Lafitte refused, believing that the US would eventually prevail in this conflict...and also reasoning that, in the future, he would have better luck evading the puny US Navy than the Royal Navy, so it was in the best interest of his business that New Orleans remain American.

Interestingly, Lafitte was aware of a pending US Navy attack on his stronghold when he refused to side with the British. Despite Lafitte's efforts to convince US authorities that they had nothing to fear from him, Commodore Daniel Patterson (1786-1839) aboard the schooner USS Carolina, along with six gunboats, captured Lafitte's stronghold on September 13, 1814. Lafitte escaped, but 80 of his underlings and a big ole pile of ill-gotten goods were nabbed by the US government.

|

Weirdly, Lafitte soon thereafter agreed to help future US President Andrew Jackson (1767-1845) in the defense of New Orleans from the attacking British army: A promise of immunity from prosecution and the early release of his brother from prison may have played a part in his sudden enthusiastic patriotism. On January 8, 1815, Lafitte and some of his crew joined Jackson's little cobbled-together army five miles outside of New Orleans at Chalmette, where the outnumbered Americans, protected by hastily-erected earthwork defenses, defeated the dreaded lobsterbacks in a lopsided victory that ended the war. Technically the War of 1812 had been over since the Treaty of Ghent had been signed on December 24, 1814...but news traveled slow.

The end of the war came too soon for any fortifications to be built on Grand Terre Island, but the necessity was still evident. Preparation of the site of Fort Livingston got underway in 1834, but was almost immediately suspended until 1840. Construction of the fort finally began in 1841, under the auspices of Major Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard (1818-1893).

|

|

Fort Livingston before it was the flooded, dilapidated (though politely charming) wreck that it is today. Sadly, it doesn't appear that anyone had the wit to photograph our fort before it was a wreck. |

|

After distinguishing himself in the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), Beauregard, who trained as an engineer at West Point, was put in charge of the Department of the Mississippi and Lake Defenses of Louisiana. Over 12 years he maintained and built forts from Florida to Mobile, Alabama: He did some work on Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip on the Mississippi south of New Orleans. On April 12, 1861, a newly-Condederatized Beauregard ordered the bombardment of Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, which marked the beginning of the American Civil War (1861-1865).

|

Fort Livingston in 2002. Fort Livingston in 2002. |

|

Fort Livingston's namesake was Edward Livingston (1764-1836), New York City's Mayor in the first years of the 19th century who relocated to New Orleans in 1804 following a financial scandal that doesn't seem to have been his fault. Livingston was well-regarded in Louisiana, where he developed an exciting provisional code for judicial procedure that modernized the hodgepodge of Roman, Spanish, French and Martian systems that were presently in use there.

Edward's brother Robert R. Livingston (1746-1813) had negotiated the Louisiana Purchase (1803), which would make him the more logical brother after whom to name a semistarfort in my opinion...

|

|

|

...but, Edward played an important role in rallying support for defending New Orleans from the British in 1815 amongst that city's ridiculously diverse population, and negotiated immunity for Jean Lafitte as payment for his participation in the battle. Plus, Edward went on to serve in the US Senate representing Louisiana, and was Secretary of State in Andrew Jackson's administration from 1831 to 1833. In this land where major fortifications are named for Presidents and military figures, either Livingston brother seems an odd choice for starfort-naming, but being on Andrew Jackson's good side carried a lot of political weight in the 1830's & 40's. Fort Livingston's appearance would be familiar to anyone acquainted with Fort Barrancas in Pensacola, Florida, as their designs are nearly identical...although Livingston is much larger than Barrancas. Both were designed by Distinguished Uncle of the American Starfort Joseph Totten (1788-1864): Simon Bernard (1779-1839, unrelated to Fort Livingston except in that he schooled Totten in the ways of the starfort, but I wanted to drop his name anyway) was probably Father of the American Starfort.  Fort Livingston from the south. In its present state, not a sight to make America's seaborne enemies quake in their schooners. Fort Livingston from the south. In its present state, not a sight to make America's seaborne enemies quake in their schooners.

Many thanks to John Weaver for the generous contribution of this and other pix on this page!

All of Fort Livingston's long guns were mounted en barbette, which is the fancy way of saying atop its walls. The counterscarp galleries, which extend outside the fort along the angle emanating from its "top," was intended to have dudes with rifles crammed inside, who would loudly and smokily disembowel any opposing force that was so unwise as to approach the fort's inner walls. |

A lighthouse was added to Grand Terre Island next to the fort in 1856. When the American Civil War began in 1861, Fort Livingston was incomplete, a state in which it remains to this day. There was a natural enthusiasm amongst Confederates for manning whatever fortifications existed in the south at the beginning of the war, and the vast majority of those forts were helpfully ungarrisoned by Federal troops. The four exceptions to this rule were Fort Monroe, Fort Zachary Taylor, Fort Pickens and Fort Jefferson.

|

|

A snake-filled moat inside a fort? Ingenious! A snake-filled moat inside a fort? Ingenious! |

|

As the alert amongst us will have noted, Fort Livingston was not one of these exceptions. A 300-or-so-man Louisiana Militia force under a General Lovell grabbed it at the outset of the war, and garrisoned what was probably already an unpleasantly damp and buggy Fort Livingston. At the time of its Confederate occupation, our fort mounted a 32-pounder, an 8-inch Columbiad, seven 24-pounders and four 12-pounders. Two howitzers were mounted in the fort's counterscarp galleries. The Confederate force was placed at Fort Livingston to protect blockade runners. These ships darted in and out of ports blockaded by the Union Navy as part of General Winfield Scott (1786-1866)'s Anaconda Plan (Scott's starfort bona fides include his capture of Fort George on the Niagara River from the British during the War of 1812). Fort Livingston may or may not have done any active protecting of such ships, but surely the presence of Confederate guns at the mouth of Barataria Bay gave the US Navy something to think about whilst chasing privateers in the area.

|

"Ruins" is such an uncharitable term. "Ruins" is such an uncharitable term. |

|

New Orleans was captured by the Union in 1862, following a spectacular naval battle around Fort Jackson on the Mississippi. The Louisiana Militia abandoned Fort Livingston, as without a New Orleans in need of supplies provided by blockade runners, there was no point to them being there. Following the war, the US Army garrisoned Fort Livingston with an irresistible force of...a single Ordnance Sergeant. |

|

|

This was in no way unusual: Plenty of US forts were manned in such a fashion for decades, with a single guy to keep an eye on things. This was in fact the reason it had been so easy for the Confederacy to grab so many forts at the beginning of the Civil War. Clearly the assumption was that threat of further such shenanigans was impossible, which was, in this case, correct.

Time marched on: A hurricane destroyed much of the fort in 1872, and most of its guns and all its ammunition were finally removed in February of 1889, when the last Ordnance Sergeant left. Fort Livingston languished, unloved, until 1923 when the US government gave Grand Terre Island and its fort to the state of Louisiana, whereupon Fort Livingston continued to languish, unloved. 1955 saw the island designated a Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Reservation, 'twas added to the National Register of Historical Places in 1974, and in 1979 it was rebranded as the Fort Livingston State Commemorative Area.

|

Hurricanes, hurricanes and more hurricanes have had their way with Fort Livingston, but Louisiana has been working to protect it from the ravages of the Gulf of Mexico. While pictures of the fort today make it plain that it's not in any shape to defend New Orleans from a fleet of Brazilian ironclads, it at least appears to be a little safer from the pounding surf than it had been in the recent past.

Following Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Fort Livingston was stabilized, and a sea wall was built around it to minimize the effect of the tides on the fort's remaining walls. About 2/3 of the structure still stands today, most of which is frequently really quite damp, and all of which is protected by various kinds of snakes and endless battalions of mosquitoes.

|

|

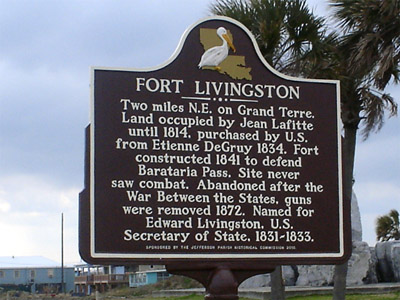

Just in case you thought I was making all of this up. Just in case you thought I was making all of this up. |

|

Fort Livingston is only accessible by boat, but is somewhat of a minor tourist attraction. The US Coast Guard, based at Grand Isle across the mouth of Baratatia Bay, keeps a close eye on things, but it seems as though folks are more or less welcome to try to not injure themselves at the fort.

Many, many, MANY thanks to American starfort scholar John Weaver, whose recent visit to Fort Livingston provided this page with pix and insight.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|