|

Fort Barrancas

Pensacola, Florida, USA

|

|

|

Constructed:

Fort Barrancas: 1839-1844

Bateria de San Antonio: 1793-1797

Used by: Spain, Great Britain, USA, CSA

Conflicts in which it participated:

War of 1812, First Seminole War,

US Civil War

|

Spanish explorer Pánfilo de Narvárez (147?-1528) and his explorative companions were the first Europeans to lay eyes on Pensacola Bay, in 1528. Hernando de Soto (1495-1542) followed in 1539, and their consensus was, and I'm paraphrasing here, gosh this is a pleasant location. That it also had a bay and lovely anchorage only made it pleasanter.

Spanish attempts at colonization in the 1550's and 60's failed due to weather, bellicose natives and a generally inhospitable climate, initial impressions notwithstanding. The Spanish authorities in Mexico, from whence these missions emanated, determined that the Pensacola region was too dangerous to colonize. |

|

|

|

Hernando de Soto also discovered the Mississippi River in May of 1541, and word had gotten around. The French began exploring up the river in the late 17th century, and in 1682 the entire Missippi River Valley was claimed for France. This may not have impressed the local Indians overmuch, but it did startle the fatally inbred Spanish King Charles II (1661-1700) into action.

|

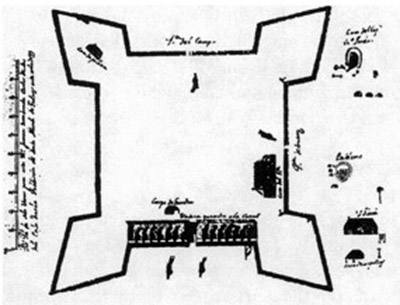

Fort San Carlos de Austria, 1699. Yep, that's a starfort all right! |

|

The Spaniards overcame their torpor and established a settlement at Pensacola, close to Fort Barrancas' current location, in 1698. The Presidio Santa Maria de Galve existed from 1698 to 1719, which featured Fort San Carlos de Austria, named for His Majesty of the Strangely-Shaped Head King Charles II, and as pleasingly standard a colonial starfort design as could be constructed at the end of the 17th century.

The English had also been busy in the area, and the Presidio's Spaniards fought off almost constant attacks from British-allied Indians. The French showed up in 1719 and kicked the Spaniards out of their Presidio, burning the timber-and-earth starfort for good measure.

|

|

|

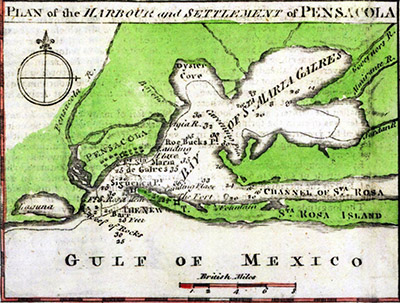

Never a people to give up easily, the Spanish established another Presidio on nearby Santa Rosa Island, today home to the spectacular Fort Pickens, in 1722. The Presidio Isla de Santa Rosa lasted until 1752, when a particularly nasty hurricane rendered it uninhabitable. The Spaniards doggedly returned to the mainland and built the Presidio San Miguel de Panzacola in 1754, about five miles east of their first Presidio. This became the kernel from whence the modern city of Pensacola was popped. The Seven Years' War (1755-1763) forced the Spanish to pull up their roots once again in 1762, as Britain's victory over France meant that western Florida was now British. Pensacola was named the British capital of Western Florida. Accordingly, the men in red built the Royal Navy Redoubt on the bluffs overlooking Pensacola Bay in 1763, where Fort Barrancas sits today.

|

The American Revolutionary War kicked off in 1775, and in 1779 the Spanish entered the fray on the side of truth and justice, which in this case happened to be with the rebels. Ever hopeful of regaining Florida, the governor of Spanish Louisiana, Bernardo de Gálvez (1746-1786), swung immediately into action. He captured Mobile in March of 1780, which city he used as a staging point for an attack on the British at Pensacola.

The British, meanwhile, had not been idle on the bluffs overlooking Pensacola Bay. They built a few other earthworks (Prince of Wales Redoubt, Queen's Redubt) and at least one real-ish earthen fort, which they named with their default moniker of Fort George.

|

|

A British map of Pensacola and its environs, from 1763. Note The Fort on Santa Rosa Island...the remains of the hurricane-ravaged Spanish Presidio? The fortlet in the center of the town of Pensacola surely depicts the Royal Navy Redoubt. A British map of Pensacola and its environs, from 1763. Note The Fort on Santa Rosa Island...the remains of the hurricane-ravaged Spanish Presidio? The fortlet in the center of the town of Pensacola surely depicts the Royal Navy Redoubt. |

|

The British had a battery on Santa Rosa Island as well, but when the Spaniards landed there on March 9 of 1781, they found it abandoned. As it turned out, the Royal Navy Redoubt certainly looked impressive, but was sited too far from the mouth of the bay to effectively prevent interlopers from storming in...which is precisely what the Spanish did (after some understandable initial hesitation) on March 19.

|

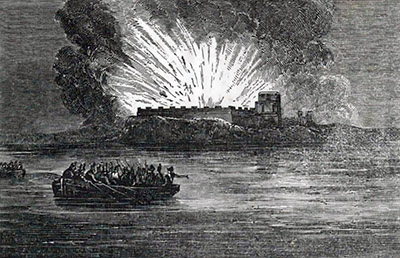

Prise de Pensacola, a 1783 etching showing a suspiciously substantial Fort George's magazine exploding. |

|

The Siege of Pensacola was one of the longest, and largest, actions of the Revolutionary War. Spanish, French, Cuban, Irish, British and American soldiers, and Choctaw and Creek warriors, all participated in the siege, which concluded on May 10, 1781 with the surrender of British commander General John Campbell (1727-1806). At the conclusion of the war, Britain ceded East Florida (separated from West Florida by the Apalachicola River) to Spain, and all Florida was once again Spanish.

Those Spaniards rebuilt the Royal Navy Redoubt in 1793 as a bastioned, wood-and-earth fort, and named it Fort San Carlos de Barrancas. |

|

|

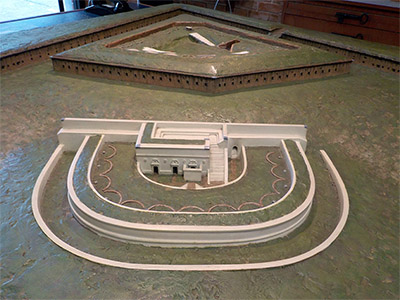

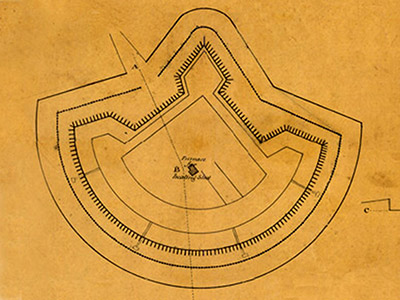

Having recently learned first-hand what happens when one's fort is too far from the thing one wishes to protect, they wisely augmented this defensive position. Just a few hundred yards down the bluffs from their new fort, the Spanish built the Bateria de Santa Antonio, which was completed in 1797. Named (maybe) for Anthony of Antioch, who had his eyes heroically pulled out with hooks in 302AD during Roman Emperor Diocletian (244-312)'s persecutions of Christians, the Bateria was closer to the level of Penascola Bay, allowing its shot to skip merrily along the water and smash, theoretically, into the hulls of attacking ships.

|

The Bateria's rounded leading edge, while perhaps slightly offensive to those of us who recognize the bastioned starfort as the most effective fortification concept (at least until the mid-19th century), was intended to give the battery's gunners the flexibility to more effectively follow ships moving along the bay before them. The cannon that the Spanish were using in this situation weren't mounted on pintles, but were essentially field pieces that could be conveniently dragged about.

During the War of 1812 (1812-1815), the young United States learned that an alliance with a European power is a fickle thing. Though neutral in this conflict, the Spanish nonetheless handed Fort San Carlos de Barrancas, the Bateria de San Antonio and other defenses in Pensacola over to the British.

|

|

A model of the Bateria de San Antonio (in its later guise of the Fort Barrancas Water Battery) advancing pugnaciously in front of Fort Barrancas, in the fort's tiny but well-appointed Visitor's Center. A model of the Bateria de San Antonio (in its later guise of the Fort Barrancas Water Battery) advancing pugnaciously in front of Fort Barrancas, in the fort's tiny but well-appointed Visitor's Center. |

|

The city of Mobile was part of the Spanish territory of West Florida, and was seized in April of 1813 by American forces under General James Wilkinson (1757-1825), and the Americans duly built Fort Bowyer at Mobile Point to defend their new acquisition. The British tried and failed to capture Fort Bowyer via naval action with a supporting diversionary land attack in September of 1814, and thus were granted permission to build up their forces at Pensacola to make a proper go at the fort, and with it control of Mobile Bay.

|

Fort Bowyer at Mobile Point: 1813-1821, RIP. Does this fort design look unusual to you? Check out Fort Pike and Fort Macomb! |

|

Having had time to prepare at Pensacola (sort of), the Brits managed to capture Fort Bowyer after a five-day siege in February of 1815. This turned out to be the last land battle betwixt the British and Americans in the War of 1812, which had technically ended on December 24, 1814, with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, and the perplexed British were forced to withdraw from Fort Bowyer when they learned of the Treaty, the day after capturing the fort. As a result of all this, Mobile was officially secured by the US from the Empire of Spain: This was the only permanent land acquisition made during the War of 1812. In 1819 work began on the supderduper-stellarlyspectacular Fort Morgan at Mobile Point, and Fort Bowyer faded into history. |

|

|

Okay now we need to back up a little. Please pardon my digression into Fort Bowyer. It's very difficult for me to pass by a starfort, particularly one that hasn't been dealt with at this site already!

Andrew Jackson (1767-1845), who had great hair, was not a man with whom one wisely trifled. Fresh from his victory over the wicked "Red Sticks" faction of Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend (March 27, 1814), Jackson was heading for New Orleans to defend it from the equally wicked British in November of 1814. On the way, he headed for Pensacola to drive out the British, who were, among other things, arming Indians hostile to the United States. Of which there were many, and perhaps rightfully so, but Andrew Jackson tended to see red when it came to the red man...and, as it turned out, men who wore red, like the British, and white, like the Spanish, and pretty much any other color, if you were something other than an American.

|

In the dawn of November 6, 1814, Jackson advanced on the town of Pensacola with 3,000 troops. They managed to skirt the British-manned forts without being fired upon, and met some resistance in the center of the town which they swiftly overcame. In all, there were only around 700 British, Spanish and Creek troops and/or braves defending Pensacola, which the Spanish Governor officially surrendered to the Americans later that day.

Jackson & co. planned on storming Fort San Carlos the following morning, but those dastardly Brits beat them to the punch by setting a charge in the fort and sneaking away in the night.

|

|

Boom goes Fort San Carlos, abandoned and mined by the British in the night of November 7, 1814. Boom goes Fort San Carlos, abandoned and mined by the British in the night of November 7, 1814. |

|

This left a destroyed Fort San Carlos, but a slightly less destroyed Bateria de San Antonio, though with all its remaining guns spiked. The British pulled out of Pensacola, never to return except as pasty-white 20th century tourists...the Spanish, however, had no intention of going anywhere. This was fine with Jackson for the moment, because he needed to rush off to become the Second-Greatest Guy in the History of the United States (George Washington (1732-1799) will always be The Greatest Guy) by defeating the British at the Battle of New Orleans (December 14, 1814 to January 18, 1815).

|

The Bateria de San Antonio's dry moat today. Not much of an obstacle for guys with ladders, but a big obstacle for guys without ladders. Do you bring ladders with you everywhere you go? Neither do I. |

|

Though the War of 1812 was over, there were still plenty of Indians who had been armed and semi-trained by the British scattered about the American landscape, intent on doing bloody mischief. Andrew Jackson headed back into Florida in March of 1818 to deal with the Seminoles, indiginous persons of Florida whose indiginosity made them, not unreasonably, indignant of European (or American, in this case) expansion into their territory.

Florida was of course still owned by Spain at this time, so Jackson's activities could technically be classified as an invasion, which enraged Spain, which was nonetheless powerless to do anything about it. |

|

|

Jackson and around 5,000 men marched around in the vicinity of the Appalachicola River, built Fort Gadsden, captured Fort St. Marks, raided villages and killed lots of people. In May of 1818 the American force headed back to Pensacola, where Indians were reportedly gathering and being supplied with guns. The Spanish Governor and his 175-man garrison abandoned the city and huddled in Fort Barrancas, from whence they traded artillery shots with the Americans for a few days until, honor upheld, the fort was surrendered to Jackson on May 28. Thanks to Andrew Jackson, Western Florida had been seized by the United States.

Action Jackson's actions caused a diplomatic kerfuffle. Spain and the United States had been negotiating over the latter's purchase of Florida from the former, which negotiations were suspended until Pensacola and St. Marks were handed back to Spain. Things in the New World were not going well for the Spanish Empire, however, and in 1819 the Adams-Onís Treaty arranged for the ceding of Florida to the United States, as well as setting a series of boundaries in the western regions of North America which were later, naturally, ignored by the United States. Because that, my friend, is how America rolls.

|

The United States officially took possession of Florida in 1821, and on July 17 of that year the Spanish flag was lowered over the Bateria de San Antonio for the last time. In 1839, the Bateria's new owners set to work on the construction of improvements: A rear wall (the back end of the battery had previously been open to the elements); a truly weird infantry gallery at the top of the battery (which resembles nothing more than a big bathtub); and mounted artillery on pintles, which was the way God intended for artillery to be mounted in a fort, thank you very much.

The other thing that happened in 1839 was that work on Fort Barrancas, as it majestically stands today, was finally begun. Finally!

|

|

A photograph of the Bateria de San Antonio in the 1820's. Oh wait, there are automobiles in this picture. Okay, you got me, it's actually from the early 1960's. Thanks, LOC.gov! A photograph of the Bateria de San Antonio in the 1820's. Oh wait, there are automobiles in this picture. Okay, you got me, it's actually from the early 1960's. Thanks, LOC.gov! |

|

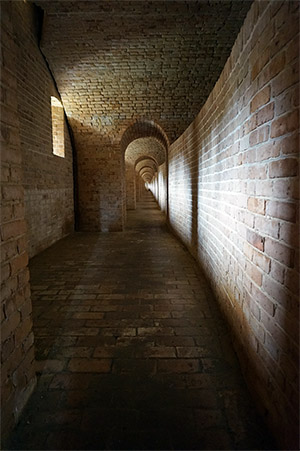

Though vaguely similar in appearance to Fort Macon in North Carolina, Fort Barrancas is unique among American forts of this size in that it was not designed to house a garrison: It is essentially a beefy raised gun platform with an infantry gallery looped around inside its base, surrounded on two sides by counterscarp galleries. The fort has no parade ground, instead being filled with earth so as to be a solid mass.

|

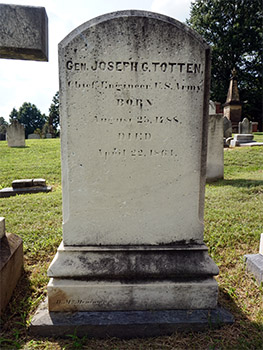

General Joseph G. Totten today, at the Congressional Cemetery in Washington DC. |

|

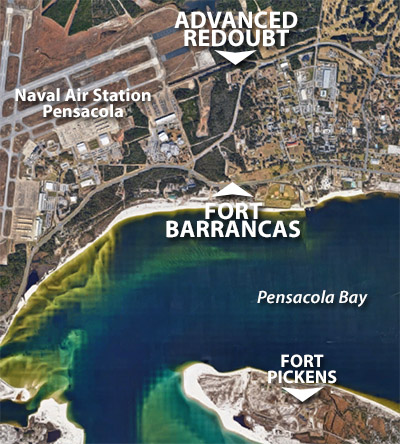

Fort Barrancas was designed by General Joseph G. Totten, America's first superstar of military engineers, and built primarily by slaves. Totten worked with, and learned from, French engineer Simon Bernard, whose American starfort accomplishments are so numerous as to preclude their listing on this page ( Fort Monroe, grandaddy of all American starforts, was one of Bernard's). Fort Barrancas and its new Water Battery, which was new only in that it was the new name for the Bateria de San Antonio, were only one cog in the new defensive system of Pensacola and its Naval Yard. Fort Pickens on Santa Rosa Island and Fort McRee on the eastern tip of Perdido Key were built to guard the inlet to Pensacola Bay, and the Advanced Redoubt protected the landward approach to Fort Barrancas. As there was no room in Fort Barrancas for guys to do anything other than man guns and point rifles out of loopholes, Barrancas Barracks was developed along the fort's left flank. Initially just a barracks building, it became a sweeping support area for the fort, eventually serving as the command center for all of Pensacola's defenses. |

|

|

Fort Barrancas and its Advanced Redoubt were completed by 1844 and, the United States being at peace with the world (unless you were an Indian), just enough men to garrison the fort in a pinch were left at Barrancas Barracks. This was the case at just about all American starforts: After the initial enthusiasm to defend American shores following the embarassing revelations of the War of 1812 (Washington DC was burnt by the British in August of 1814, after the only defensive work built along the Potomac River to defend the city from exactly such an invasion, Fort Warburton (in the location that would later be home to Fort Washington), had blown itself up in the (erroneous) expectation of being attacked from its undefendable landward side), the US government found itself disinclined to pay for their forts' garrisons and upkeep. In many cases, completed forts weren't even armed, certainly not up to the levels for which they had been designed.

|

And it is in this era of new, undermanned forts sprinkled along the coastline of the southern United States, that we come to the US Civil War (1861-1865). In January of 1861 Florida's Legislature voted for secession from the United States, news of which reached Lieutenant Adam J. Slemmer (1828-1868), commander of the 50-man Federal force currently in charge of Forts Barrancas, Pickens and McRee: These troops were stationed at Fort Barrancas, with only teeny caretaker units at Pickens and McRee.

Alerted to rumors of state militias that might have an interest in nabbing these forts for the forthcoming Confederate cause, Slemmer's troops were ready for trouble, which came on the night of January 8, 1861.

|

|

Barrancas Barracks in 1903. Barrancas Barracks in 1903. |

|

A company of Alabama Militia had been told that Fort Barrancas was deserted, and came to investigate and hopefully occupy the fort. They were met at the fort's drawbridge by a Sergeant's guard, which opened fire on the shadowy figures when they would not identify themselves. The militiamen skedaddled: There were no injuries. These were, arguably, the first shots fired in the Civil War, over three months ahead of the cannonade at Fort Sumter.

|

Fort Barrancas' infantry gallery, or scarp gallery. "Scarp" is a sound effect, not a word. |

|

Recognizing how much easier it would be to defend Fort Pickens with his small force, two days after chasing off the Alabama Militia Slemmer had Fort Barrancas' 30-ish guns spiked (nails driven into the cannons' touchholes, making them incapable of firing without a lengthy and painstaking process of drilling out those nails), loaded up a flatboat with ammo and supplies, and paddled out to Pickens. Thanks to Slemmer's quick action, Fort Pickens would be one of only four major forts in the southern United States ( Fort Monroe, Fort Zachary Taylor and Fort Jefferson were the other lucky ones) that were held by the Union throughout the Civil War. The Confederacy naturally took possession of all of Pensacola's defenses that were not Fort Pickens, and they certainly wanted Fort Pickens, and made at least one serious attempt to take Fort Pickens, but ultimately had to content themselves with a few fruitless artillery exchanges with Fort Pickens. Sadly, the Confederacy's occupation of Pensacola never really worked out the way they had hoped. The US Navy and Union-occupied Fort Pickens effectively closed Pensacola Bay to Confederate shipping, and once Federal troops had captured New Orleans in the Spring of 1862, the men in grey withdrew from Fort Barrancas and the rest of Pensacola. |

|

|

The Union swept back into Pensacola and its fortifications. Fort Barrancas was used as a staging ground for several raids into Confederate territory, but the days of the masonry fortification as an impregnable artillery platform were over. Fort Barrancas was used for various secondary purposes by the US Army until the end of the Second World War (1939-1945), but Endicott Period batteries for huge guns were added to Fort Pickens and Fort McRee in the late 1890's, which handled the defense of Pensacola Bay from potential marauding European navies.

|

Just a smidgen to the nor'west of Fort Barrancas, Naval Air Station Pensacola began its existence in 1914. The NAS exploded in both size and importance through two World Wars, and when Fort Barrancas was officially deactivated from military service on April 15, 1947, it was assimilated into (or "brought aboard," as the Navy uses such terminology on land bases) the Naval Air Station.

Fort Barrancas and Pensacola's other remaining defenses were integrated into the Gulf Islands National Seashore in 1971, a National Park run, fittingly, by the National Park Service. Fort Barrancas and especially its Water Battery were extensively restored, and they were opened to the public in 1980.

|

|

The entirety of what I would call Fort Barrancas' parade ground, only no parading ever occurred on this ground. And my intrepid starforting daughter. The entirety of what I would call Fort Barrancas' parade ground, only no parading ever occurred on this ground. And my intrepid starforting daughter. |

|

Fort Barrancas & Water Battery before (1962) and after (2017) its Federal restoration funding. Fort Barrancas looks outwardly pretty much the same, but the Water Battery looks much better!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|