|

Fort Gaines

Mobile, Alabama, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1853 - 1862

Used by: USA, CSA

Conflict in which it participated:

US Civil War

|

Fort Gaines is one of several impressive forts seemingly built by the US government in the south prior to the US Civil War for the express purpose of leaving them unmanned and ready to be effortlessly captured by the Confederacy.

Mobile (known initially as Fort Louis de Louisiane (because they had built a fort there)) was the first capital city of the French colony of Louisiana, founded in 1702. The name Mobile comes from the Indian tribe that the French encountered living in this area, whose name likely sounded something like "Mobile."

It was reasoned that the Indians didn't deserve possession of this lovely natural harbor, as they had no oceangoing ships to park in it, and the French, who did have a bunch of really big ships, logically made it their own.

|

|

|

|

The original town was located a few miles up what is today the Mobile River, but by 1711 it had been moved to its present location, where the river meets the bay, due to constant outbreaks of disease and flooding at the town's old spot. The French built a new, earthen Fort Louis to solidify the new location.

The capital of the Louisiana colony was moved to Biloxi in 1720, and Mobile was left as a military and trading center. A proper French military town can't have a mere earthen fort, so an actual masonry starfort was begun in 1723: Fort Condé. This would be a starfort absolutely deserving of its own writeup at this site, only it's not really there any more, other than a partial reconstruction...so let us not trouble ourselves further with starforts with funny letters in their names at this time.

|

|

|

The conclusion of the Seven Years' War (1756-1763) forced France to cede all of its lands in America east of the Mississippi River to Great Britain. Mobile suddenly found itself to be part of the British province of Western Florida, and was a haven for royalist Americans during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783).

Spain piled onto Great Britain while the latter was occupied with wrangling its wayward colonies, capturing Mobile in 1780. |

|

The United States finally got its hands on Mobile in 1813, as part of the War of 1812 (1812-1815). Elsewhere during this conflict, Brigadier General Edmund P. Gaines (1777-1849) was in command of the US force at the captured Canadian starfort Fort Erie when, on August 15, 1814, the Americans bloodily repulsed a British attempt to retake the fort. While this successful action may have had as much to do with the overpoweringly defensive nature of a starfort as with Gaines' superior leadership, Gaines was awarded the Thanks of Congress, an "Act of Congress Gold Medal." While I had never heard of this award before, it was given to a series of American military men and units of distinction from the Revolutionary War up to the First World War (1914-1918). Fellow starfort namesake Alexander Macomb (after whom Fort Macomb would be named) was also awarded this medal for his role in the Battle of Plattsburgh during the War of 1812.

|

In 1821 work began on Fort Morgan, as stellar a starfort as ever was. Placed on the tip of a spit of land that slides into the mouth of Mobile Bay from the east, Fort Morgan was intended to protect the rapidly-growing city of Mobile, which had developed into an important waypoint for both the cotton and slave trades. A similar fort was planned for Dauphin Island, which formed the western side of the entrance to Mobile Bay. Work on that fort had begun in 1819, but a series of budgetary and construction problems killed the project before much more than foundations could be built. By the time the government was ready to get back to work on the fort that would become the starfort of our current interest, a revolution in fortification design had changed everything. Or, mostly everything. The state-of-the-scientific-art-of-fortification entering the 1850's was the polygonal fort. |

|

A bit of a criminally small copy of a plan of Fort Gaines from the 1850's. This plan is held by the Library of Congress, yet I can't seem to access it at their website. Meanwhile, this teeny smidgen is all we have to look at. I am ashamed. |

|

The polygonal fort was pioneered at the end of the 1700's, and became popular in the middle of the 19th century. The starfort had been designed to counter an attacker with smoothbore cannon firing round shot, but by the middle of the 19th century, rifled cannon firing explosive shells was recognized to be the coming thing in warfare. A polygonal fort is also known as a flankless fort, for its seeming lack of vulnerable points. Built lower to the ground with more interior protective structures (deep fortified tunnels leading to its stoutly-built, blockhouselike bastions), the polygonal fort was the starfort concept taken to the next level. To me, this means a polygonal fort is still a starfort. But then I've always been very good at convincing myself of unlikely things.

|

Inside one of Fort Gaines' bastions. Inside one of Fort Gaines' bastions. |

|

One of the most exciting things about starforts is that there are really no two that are exactly alike. Built during a time when there were no systems in place to centralize the control of fort design and construction, each was its own local affair, built for its own specific purpose. By the 1850's, however, there most certainly was a regulatory body in charge of such things in the United States, and as a result of this, Fort Gaines is a carbon copy of a few other polygonal forts of this period, such as Fort Clinch on Amelia Island, Florida. I visited Fort Clinch in 2014, and the interior shots I'm finding of Fort Gaines look extremely familiar to me. |

|

Fort Gaines was designed to mount ten guns on each of its five curtain walls, and four flank howitzers in each of its five bastions. It was surrounded with a 35-foot-wide dry moat, and its walls were 22 feet high. On January 11, 1861, Alabama seceded from the Union. Shortly thereafter, Alabama State Militia seized both Fort Gaines, which was nearing completion, and Fort Morgan, which had been finished in 1834. This was by no means an uncommon occurrence at the beginning of 1861. In fact only two major forts in the American south had been garrisoned by the US Army to the point where they could offer any sort of resistance to seizure: Fort Monroe at Hampton Roads on the Chesapeake bay, and Fort Jefferson off the Florida Keys. While the rest of these hugely expensive fortifications in the south hadn't been exactly abandoned by the US government in the days before the US Civil War, they might as well have been, as they were manned with one or two Ordnance Sergeants, tasked with "keeping an eye on things." A starfort is an eminently defensible edifice, but does need more than one or two guys to man the guns. |

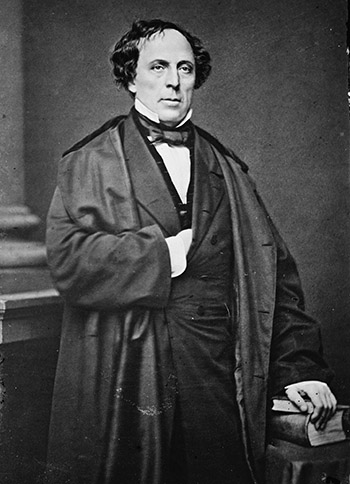

One of the main reasons for this situation seems to have been President James Buchanan (1791-1868)'s Secretary of War from 1857 to 1860, John B. Floyd (1806-1863). A former Governor of Virginia, Floyd may or may not has used the office of Secretary of War to unduly financially benefit himself (his 1861 indictment for "Malversion of Office" was overturned on technical grounds), but what Floyd most definitely did do was send large amounts of ordnance and supplies to those southern forts, while simultaneously moving Federal troops out of those forts.

In the words of Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885), Commanding General of the US Army from 1864 to 1869 and 18th President of the United States: "Floyd, the Secretary of War, scattered the army so that much of it could be captured when hostilities should commence, and distributed the cannon and small arms from Northern arsenals throughout the South so as to be on hand when treason wanted them."

Had the powerful forts in such cities as Charleston (Fort Moultrie), St. Augustine ( Castillo de San Marcos), Savannah ( Fort Pulaski and Fort James Jackson) and Mobile been properly garrisoned by US troops in January of 1861, many southern states may have had a much more difficult time gaining military traction upon their secession. |

|

John B. Floyd, President James Buchanan's Secretary of War leading up to the US Civil War. No friend to the starfort. Please note that there is no "Fort Floyd." John B. Floyd, President James Buchanan's Secretary of War leading up to the US Civil War. No friend to the starfort. Please note that there is no "Fort Floyd." |

|

Floyd went on to become a general in the Confederate Army, a position in which he did not do well. Following the Confederate defeat at the Battle of Fort Donelson in February of 1862, he was far more worried about the possibility of being captured and immediately hung than he was about the welfare of his men, and appropriated lots of transportation and supply assets to ensure his own getaway...for which he was relieved of command. Excellent choice for Secretary of War there, President Buchanan.

But we were talking about Fort Gaines, weren't we. Fort Gaines' new owners finished building the fort in 1862. The combination of Forts Gaines and Morgan (plus a string of 67 naval mines, known colloquially as "torpedoes," strung across the mouth of the bay betwixt the two forts) kept the US Navy out of Mobile Bay until 1864. In August of that year, Rear Admiral David Farragut (1801-1870) showed up with a fleet of eighteen US Navy ships, four of which were turreted ironclads of the Monitor design.

|

The Battle of Mobile Bay by J.O. Davidson, 1886. Ironclad USS Tecumseh strikes a "torpedo" before Fort Morgan. The Battle of Mobile Bay by J.O. Davidson, 1886. Ironclad USS Tecumseh strikes a "torpedo" before Fort Morgan. |

|

Fort Gaines was garrisoned by 818 men, and mounted 26 guns at this time. On August 3, 3,000 Federal troops landed on Dauphin Island some 15 miles west of Fort Gaines, and managed to construct siege entrenchments to within a half mile of the fort.

On August 5th, Rear Admiral Farragut's fleet attacked. The string of "torpedoes" was well-marked by buoys, intended less to surprise attackers than to keep them within range of the defending forts' guns. Twas during this battle that Farragut bellowed the heroic phrase that is generally paraphrased today as, "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!"

|

|

The Union fleet blasted through the mines, in the process losing the ironclad USS Tecumseh. Once inside Mobile Bay, Farragut found that the guns of Fort Gaines, Fort Morgan and Fort Powell (a small fort of seven guns and five field howitzers, in the bay just a smidge north of Fort Gaines) were unable to bear on the Union fleet, and were completely vulnerable to fire from their rear.

And fired upon the rear these forts most certainly were. Fort Powell's garrison scampered away immediately, but Fort Gaines' commander, Colonel Charles DeWitt Anderson (1828-1901), held out for three more days. The garrison of Fort Gaines consisted of a large number of conscripts and reservists, many of whom were "mere boys," and none of whom could properly shelter from the US Naval bombardment. Noting that his officers and men were demoralized and likely to mutiny, Anderson surrendered Fort Gaines on August 8.

|

Though the forts protecting Mobile Bay had been vanquished (Fort Morgan finally surrendered on August 23rd) and garrisoned by Federal troops, the city of Mobile remained defiant until three days after Robert E. Lee (1807-1870)'s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse: Mobile surrendered to the Union on April 12, 1865. Fort Gaines was reactivated in 1898, as the explosion of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor on February 15 of that year had pretty much convinced the entire United States that an overwhelming invasion by the Spanish Armada was imminent. Three Endicott Period batteries were built in and around Fort Gaines from 1898 to 1901. |

|

Sitting in the center of Fort Gaines' parade ground is one of the anchors from the USS Hartford, Rear Admiral Farragut's flagship during the Battle of Mobile Bay. To the left is Battery Stanton, one of Fort Gaines' Endicott Pyriod batteries. Sitting in the center of Fort Gaines' parade ground is one of the anchors from the USS Hartford, Rear Admiral Farragut's flagship during the Battle of Mobile Bay. To the left is Battery Stanton, one of Fort Gaines' Endicott Pyriod batteries. |

|

The first battery was begun in 1898 and intended to mount two 8" Rodman Guns. Someone must have realized that Rodman Guns were, like, soo 1863, because that battery was not finished: Instead, Battery Stanton (named for Captain Henry B. Stanton of the 1st US Dragoons, who died fighting Apache Indians in New Mexico in 1855), mounting three 6" Disappearing Guns, was built o'ertop this original, unnamed battery, beginning in 1899. These are the mounts that are visible within Fort Gaines' interior.

|

Guard that bay, 32-pounder seacoast cannon. Guard that bay, 32-pounder seacoast cannon. |

|

Outside the fort, Battery Terrett, named for First Lieutenant John C. Terrett, who died in the Battle of Monterrey (September 21-24, 1846) during the Mexican-American War (1846-1847). This battery mounted two 3" quick-firing guns.

But the wicked Spaniard did not come out to play. Fort Gaines was again reactivated during the First World War (1914-1918), for a period serving as an anti-aircraft gunnery school. |

|

Again, no Spaniards. Though the government sold Fort Gaines to the state of Alabama in 1926, the Second World War (1939-1945) brought the Alabama National Guard and the US Coast Guard back to Fort Gaines once again.

Today, Fort Gaines is open to the public year 'round, but is listed as one of the Eleven Most Endangered Historic Sites in America due to ongoing shoreline erosion. Get there and visit Fort Gaines before it washes away!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|