|

Fort Moultrie

Charleston, SC, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1776 - 1809

Used by: USA, CSA

Conflict in which it participated:

US Revolutionary War,

US Civil War

|

Expecting British poundings at the port of Charles Towne, South Carolina, patriots began work on the first iteration of what would become Fort Moultrie in 1776. Sullivan's Island, which sits at the mouth of the entrance to Charles Towne Harbor, was the location of this structure made of palmetto logs.

The fort was unfinished and unnamed when nine Royal Navy ships, under Admiral Sir Peter Parker (1721-1811) showed up with malicious intent on June 28, 1776.

|

|

|

|

Along with the nine warships came General Sir Henry Clinton (1730-1795) and 1500 men, some of whom were landed on a nearby island with the plan of wading to Sullivan's Island at low tide: No such wading was possible, so a naval bombardment ensued.

Legend has it that, during the 16-hour bombardment, the British ships' shots were unable to damage the magical palmetto logs, which caused the balls to either bounce harmlessly away or become gently, lovingly absorbed by the soft wood. Or perhaps both, simultaneously! The British ships were however not made of magic palmetto, and retired, badly battered, unable to defeat the American fort. Charles Towne was saved from British capture...for four years, when the British returned with 14,000 troops in 1780 and finally took the city. The Brits relinquished Charles Towne in 1782, when the war was winding down. Once the city was back in American hands, the residents said, this is no longer your towne, Charles, and renamed the city Charleston.

The 1776 American victory, however, one of the first in the US Revolutionary War (1776-1783), led to such joyous euphoria in South Carolina that, not only was the fort named for William Moultrie (1730-1805), its commanding officer during the battle, but to this very day the state flag of South Carolina sports a palmetto tree, South Carolina is the Palmetto State, and every June 28 South Carolinians celebrate Carolina Day, commemorating the victory. Thank you, mooshy yet impenetrable-to-cannonballs palmetto logs! |

After the US' independence was assured by a satisfactory conclusion to the war, everybody figured this silly war business was over with forever, and Fort Moultrie, along with every other ramshackle fortification along the US coast, was left to the elements. In 1793 Great Britain and France began the warring process that would eventually lead to Napoleon (1769-1821) taking over the universe. America knew that such a conflict would wind up in the western hemisphere sooner or later, so began the First System of US Coastal Fortification. This program led to such awesome US starforts as Fort Adams, Fort Norfolk, Fort Trumbull and Fort McHenry, among others. |

|

One of the corners of Fort Moultrie's NE bastion. Note the Harbor Entrance Control Post, which looks strikingly similar to that at Fort Monroe at Hampton, Virginia, as they were both built at the same time for the exact same purpose.

|

|

The second Fort Moultrie was completed atop the ruins of the first in 1798, though it doesn't seem as though #2 was any more substantial than #1: A hurricane in 1804 completely destroyed it. The third and final version of Fort Moultrie was completed in 1809, the vision of brick loveliness that we see today. 'Twas designed by a young officer of the US Corps of Engineers, Alexander Macomb (1782-1841). Macomb would go on to not only command the US Army from 1828 until his death, but, more importantly, have a pseudo-starfort named after him: Fort Macomb semi-successfully defended New Orleans from various nasties through much of the 19th century. Charleston was unvisited by the British during the War of 1812 (1812-1814), but in the enthusiastic burst of postwar US fortbuilding, work on Fort Sumter began in 1829. An artificial sandbar was built in the entrance to Charleston's harbor, and Sumter was built atop, from whence it easily commanded the channel. This was perfectly swell for Charleston, but poor brave Fort Moultrie was suddenly a second-class citizen, as Charleston's defense complex increasingly concentrated on the newer, entirely unstarrish, Fort Sumter. |

Fort Moultrie in 1861. Note the beautiful hot shot furnace on the right! Fort Moultrie in 1861. Note the beautiful hot shot furnace on the right! |

|

In 1837 Seminole Indian chief Osceola (1804-1838) was invited to Fort Moultrie for "peace talks," a ruse that was frequently used by the US military to capture peskily warlike, yet foolishly trusting injuns. He and around 200 of his men were gently detained and sent to Fort Marion at St. Augustine, Florida, to cool their jets for a couple of months, and then returned to Fort Moultrie where Osceola died of quinsy (a complication of tonsillitis) on January 30, 1838. He was buried near the sallyport entrance to Fort Moultrie, where his grave remains today.

|

|

|

South Carolina seceded from the Union on December 20, 1860. Major Robert Anderson of the US Army was the commander at Fort Moultrie, and decided not to surrender his men and position to South Carolina forces, as the Federal garrisons of Charleston's other forts were cheerfully doing. Anderson moved his men to the easier-to-defend Fort Sumter on December 26, which resulted in the opening act of the US Civil War (1861-1865). Confederate forces shelled Fort Sumter into submission in April of 1861, which officially got that really quite scintillating war a-rollin'. Anderson's nerves were shot by the experience, but he was hailed as the first Union hero of the war. Promoted to Major General, Anderson was shuffled from command to command at various undemanding, peaceful posts: For a brief period he commanded Fort Adams in Newport, Rhode Island, far from those noisy rebels. Federal ironclads and shore batteries closed in on Fort Moultrie in April of 1863, pounding it over the next 20 months with rifled cannon, whose range far exceeded that of the guns at the fort. The Confederacy finally abandoned Fort Moultrie, and the city of Charleston, in February of 1865. Fort Sumter had been reduced to rubble, but much of Fort Moultrie was saved by an infantile yet brilliant Confederate strategy of aggressively piling sand on top of it! This protected the walls from much of the force of incoming rounds, plus made it more difficult for Federal gunners to aim: If all one sees is a pile of sand, at precisely what does one aim?

|

In a pattern familiar to many US coastal forts after the Civil War, Fort Moultrie was first upgraded in the 1870's, when larger, rifled guns, bombproofs and underground magazines were added. In the 1880's all of Sullivan's Island was turned into a military reservation, as there had to be room for all the dudes who were needed to man all the stuff that was being built!

Another round of improvements came at the end of the 1890's, thanks to the efforts of William Crowninshield Endicott (1826-1900), Secretary of War under President Grover Cleveland (1837-1908).

|

|

A 4.7" gun, dating from Fort Moultrie's Endicott Era upgrade A 4.7" gun, dating from Fort Moultrie's Endicott Era upgrade |

|

By 1904 there were nine modern gun batteries on Sullivan's Island, three of which were inside the walls of Fort Moultrie. The new guns varied in size from huge 12" mortars to 3" rapid-fire guns. During the First World War (1914-1918) all of Fort Moultrie's big guns were dragged to Europe, and few of them were ever replaced. Those that were replaced were considered completely obsolete by the start of the Second World War (1939-1945), and many fell victim to the first big US scrap drive in 1942. A Standard Issue US Government Harbor Entrance Control Post was built at the fort in 1944, from whence shipping in and out of Charleston Harbor was monitored and directed.

|

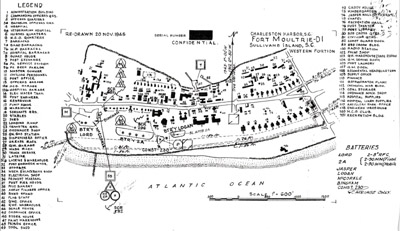

The Fort Moultrie Military Complex in 1945. Thanks, Fortwiki.com! The Fort Moultrie Military Complex in 1945. Thanks, Fortwiki.com! |

|

Fort Moultrie was finally closed on August 14, 1947, completing 171 years of active service. The Department of Defense turned the fort over to the National Park Service in 1960. Today Fort Moultrie is operated as a unit of Fort Sumter National Park, and is open year 'round. Representations of each of the fort's defensive eras, from the magic palmetto structure to World War Two's Harbor Entrance Control Post, allow visitors to stroll through history without being shot at. Usually.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|