|

Fort Frederick

Kingston, Ontario, Canada

|

|

|

Constructed: 1812, 1846-1848

Used by: Great Britain, Canada

Conflict in which it participated:

War of 1812

|

In the last half of the 18th century, Great Britain had hopes of retaining its empire in the New World. This despite having been ejected from the United States, because there was still plenty of Canada to go around. A relatively small portion of Canada was actually of direct interest to Britain, namely the settlements along the St. Lawrence River and Great Lakes...one of which was called Cataraqui, a name that may have been a derivation of the Iroqouis word for "where one hides." The French had hidden there beginning in 1673, when they built Fort Cataraqui, later to be named Fort Frontenac. |

|

|

|

A settlement grew around the fort, but the French manned their post at Cataraqui only fitfully. The British finally did away with Fort Frontenac in 1758, during the Seven Years' War (1756-1763)...and then finally took possession of whatever was left of it in 1783, at which time they "partially" rebuilt it.

What made Cataraqui, soon to be renamed Kingston, such a desirable place for white guys of varying nationalities was its location on Lake Ontario, which the mighty St. Lawrence River drains into the Atlantic....and the Cataraqui River, which also meets Lake Ontario at this spot. The St. Lawrence connects the Great Lakes with the ocean in a navigable fashion, which was not a resource at which to scoff at this time and place.

Loyalists who had supported the British crown in the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) naturally had to leave the new United States when the British unexpectedly lost that conflict, and many settled in Cataraqui. It was being called "King's Town" by 1787, which was shortened to Kingston shortly threafter.

|

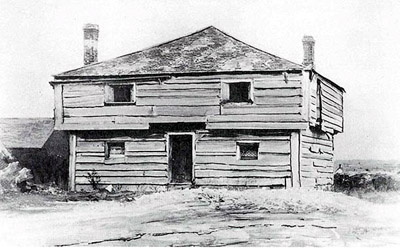

Frederick Point's first fortification, the blockhouse depicted in the drawing atop, lives on today in the diminutive little corner of masonry at the foot of Fort Frederick's majestic Martello Tower. Frederick Point's first fortification, the blockhouse depicted in the drawing atop, lives on today in the diminutive little corner of masonry at the foot of Fort Frederick's majestic Martello Tower. |

|

Point Frederick (named either for Frederick, Prince of Wales (father of King George III) or Sir Frederick Haldimand, Royal Governor of Canada in 1764) is a peninsula that sticks out where the Cataraqui meets the St. Lawrence, where they both meet Lake Ontario. A British naval dockyard was established there in 1789, which was used first as a depot and then as a base for the Provincial Marine, the fledgling naval force that was initially intended to ferry men and supplies about Lake Ontario and Erie, but which developed into a fighting force...albeit one of dubious efficacy. The American Revolution Rematch (also known as the War of 1812 (1812-1815)) kindled understandable British unease over the potential of American incursion into Canada. A 40-foot square blockhouse was built at Point Frederick over the winter of 1812-1813 to protect the dockyard. Earlier efforts at nearby Point Henry had resulted in a starfortish entity known as Fort Hamilton, which had been built on the strategically elevated spot which is today the home of the really quite fantastic Fort Henry. These fortifications proved their worth in November of 1812, when they helped to deter a small US Navy fleet. |

|

This minifleet of seven vessels was commanded by Commodore Isaac Chauncey (1772-1840), whose desire was to capture, sink or otherwise discombobulate the Provincial Marine's flagship on Lake Ontario, the Royal George. Armed with 22 32-pounder carronades, the Royal George didn't compare favorably with the vast ships o' war asail in the Atlantic, but given the size of other craft afloat in Lake Ontario, it was theoretically big enough to dominate the lake.

Chauncey's raid on Kingston was unsuccessful in that it failed to capture or destroy the Royal George, but the American fleet did manage to do away with several of the Provincial Marine's smaller ships...and the attack had certainly wreaked havoc upon Kingston. The guns on Points Frederick and Henry were ultimately too small to do major damage to the Americans, but the flurry of artillery fire from various points ashore did make things difficult for Chauncey's fleet. The Provincial Marine's poor showing in the fracas (its officers and men had little in the way of military training or experience) and shore batteries' relative ineffectiveness served as a wakeup call for the British: The Royal Navy was needed to secure Lake Ontario.

|

After the war, Canada's British overlords determined that a logical American invasion route would drive up the St. Lawrence, cutting off Kingston from Montreal. To add more flexibility for strategic transit betwixt these two cities, the British constructed the Rideau Canal from 1826 to 1832. This canal integrated various existing waterways to connect Kingston and Montreal...and it is thanks to this canal, and the need to protect it, that we have the Fort Frederick that we admire today (technically I suppose we can thank the United States for Fort Frederick: Without the omnipresent threat of American aggression through much of the 19th century, Canada would be a much less interesting place to those of us who enjoy fortifications!). Fort Frederick's three-bastioned trace came into existence in 1832, but its signature entity, the graceful Martello Tower, didn't appear until 1846. The 1813 blockhouse stood sentinel behind the new earth-and-timber walls of Fort Frederick until it was demolished in the early 1840's to make room for the much-maligned (by me) Martello Tower. |

|

Points Frederick and Henry, along with their attendant fortifications around the time of the War of 1812, from a sign at Fort Frederick...so you know it's accurate! Points Frederick and Henry, along with their attendant fortifications around the time of the War of 1812, from a sign at Fort Frederick...so you know it's accurate! |

|

And, parenthetically, I do have to admit that I've come around on the subject of the Martello Tower. As with other fortificational concepts that I initially found threatening to the purity of the starfort (such as the Guérite), after having spent a little time with and in a Martello Tower recently in Kingston, I can now understand why the British military thought they were so darned swell. Lesson learned: Get to know the things that you think you hate, and you might not hate them any more. Conditions apply.

|

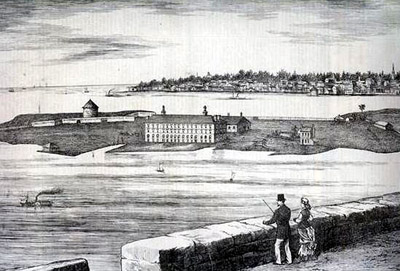

"I say, Lucretia! Isn't the view of Frederick Point simply smashing from this, the vantage point of Fort Henry's Advanced Battery, in the year of our Lord 1874 or so?" Also visible to the right of Fort Frederick is the HMCS Stone Frigate, a naval storehouse built in the 1820's which was later incorporated into the Royal Military College as a dormitory...which Hortense could have told Lucretia had he just looked it up on Wikipedia like a normal person. "I say, Lucretia! Isn't the view of Frederick Point simply smashing from this, the vantage point of Fort Henry's Advanced Battery, in the year of our Lord 1874 or so?" Also visible to the right of Fort Frederick is the HMCS Stone Frigate, a naval storehouse built in the 1820's which was later incorporated into the Royal Military College as a dormitory...which Hortense could have told Lucretia had he just looked it up on Wikipedia like a normal person. |

|

Kingston's defenses were enhanced by the addition of four Martello Towers by 1848, in response to the Oregon Question, which brought the United States and Great Britain close to war (again). The conflict over the Pacific Northwestern border betwixt the US and Canada was resolved peacefully, but not before Kingston got its shiny new Martello Towers: Cathcart Tower, Murney Tower and Shoal Tower were built during this period, as well as the one within Fort Frederick. These four, added to the two towers that had been built as satellites of Fort Henry earlier in the 1840's, made Kingston one of the most heavily Martello-Towered cities in the known universe. The masonry wall protecting Fort Frederick's landward side was built during this period, a fact which I can state with assurance because of this picture. |

|

The 1840's also provided another reason for Great Britain to conclude that Canadian fortification was in order: Rebellion. Canadians, whatever their faults, were not idiots. The American and French revolutions, as well as a series of uprisings in Spain and Portugal's South American colonies, illustrated that people need not be ruled by irresponsible, faraway monarchies. In 1837 and 1838 the otherwise placid Canadians rebelled against a surprised Great Britain, with the poetic rallying cry of Responsible Government! These rebellions were put down swiftly, but the experience got Britain thinking about further Canadian fortification.

|

Fortunately, the experience also helped show Britain the wisdom of moving Canada towards independence. Further animosity occurred during the American Civil War (1861-1865), when Britain's support of the Confederacy caused the Union to focus a gimlet eye on its neighbor to the north...but once that nonsense was resolved, the days of Canada and the United States being at serious odds with one another were over. Canada was declared independent from Great Britain on July 1, 1867.

Absent a belligerent enemy waiting on the other side of Lake Ontario to do Canada harm, Kingston's many fortifications were suddenly purposeless. Fort Frederick was abandoned in 1870.

|

|

Inside the bombproof/powder magazine under Fort Frederick's southernmost bastion. *I* certainly felt safe from bombs! Inside the bombproof/powder magazine under Fort Frederick's southernmost bastion. *I* certainly felt safe from bombs! |

|

The Military College of Canada was established in 1874, and in 1876 it made its home on Point Frederick, right behind the starfort/Martello Tower of our current interest. As part of the college campus, Fort Frederick became a space in which cadets could relax, without regard to rank. For a period the gun deck on the top level of Fort Frederick's Martello Tower was designated as a hangout spot for upperclassmen, until repeated occurrences of high-spirited young gentlemen rolling cannonballs down the tower's stairwells made the gun deck off-limits to all except the newest recruits, who presumably would be too timid to roll cannonballs down stairs.

|

The gun deck of Murnay Tower, another of Kingston's Martello Towers that was built at the same time as that at Fort Frederick...and therefore presumably very similar. Note the mobile Hot Shot Furnace to the right, which would have been scuttled out of the way as the big 32-pounder Blomfield Gun was swung around to address targets. Which it never did of course, but you get the picture. The gun deck of Murnay Tower, another of Kingston's Martello Towers that was built at the same time as that at Fort Frederick...and therefore presumably very similar. Note the mobile Hot Shot Furnace to the right, which would have been scuttled out of the way as the big 32-pounder Blomfield Gun was swung around to address targets. Which it never did of course, but you get the picture. |

|

Alexander Mackenzie (1822-1892) served as Canada's second Prime Minister, from 1873 to 1878. He had been the foreman on the construction of the four Martello Towers built in Kingston in the 1840's, and as Prime Minister he paid a visit to Frederick Point prior to the establishment of the Royal Military College there.

Mackenzie asked the college's commandant if he knew the thickness of Fort Frederick's outside wall. The commandant naturally did not, and the Prime Minister said, "It's five feet six inches, I know for I built it myself!" Which sounds like a pretty dicky thing to say, but much would have depended on the tone of voice and context, both of which we are unable to determine. Hopefully, everyone had a good chuckle over this light japery and moved on. |

|

The Great Depression of the 1930's sure was depressing in a lot of ways, but the public works programs that were spawned by governments that were frantically trying to occupy the many unemployed folks who might otherwise get up to mischief, and/or be unable to feed their families, were a boon to such entities as long-neglected starforts! Fort Frederick's outer masonry wall was reconstructed during this period.

|

In more recent years, Fort Frederick has been open to the public, with its Martello Tower operating as a museum. When I visited in August of 2019, however, the fort was closed, with plenty of evidence inside of improvements being made to the tower: One of its four caponnieres had some sort of orange diaper affixed to it, and numerous blocks of fresh white granite were dumped in the eastern bastion, out of the way but ready for use. Should you be so inclined, please visit the Fort Frederick page in the Starforts I've Visited section for pix and observations from my visit thereto. |

|

Fort Frederick's interior, from atop its southernmost bastion's gun carriage. Fort Frederick's interior, from atop its southernmost bastion's gun carriage. |

|

|

|

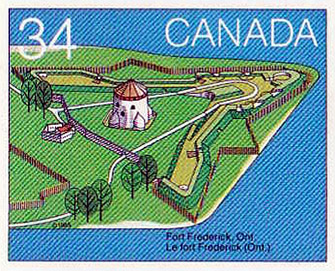

Left: In 1985, Fort Frederick was featured in the second batch of Canada Post's Forts Across Canada series of commemorative stamps. Left: In 1985, Fort Frederick was featured in the second batch of Canada Post's Forts Across Canada series of commemorative stamps. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|