|

Fort Henry

Kingston, Ontario, Canada

|

|

|

Constructed: 1832 - 1836

Used by: Great Britain, Canada

Conflicts in which it participated:

None

|

Consider, should you be so inclined, Canada in the 17th century. 'Twas a land crammed full of valuable fur, pesky native inhabitants and way more thousands of miles of trackless wilderness than most anyone in Europe had henceforth imagined. The Vikings may have been Canada's first caucasian interlopers, but France was the first to take it seriously.

|

|

|

|

And the British weren't far behind. It was for this reason that the French built Fort Cataraqui (later known as Fort Frontenac) at the Cataraqui trading post in 1673. At this trading post, located where the Cataraqui and Saint Lawrence Rivers meet and drain into Lake Ontario, Frenchmen traded in fur with the Iroquois. Fort Frontenac was captured and destroyed by the British in 1758, during the French and Indian War (1754-1763). The British, justifiably chuffed with themselves, returned across the lake to the lovely Fort Ontario.

|

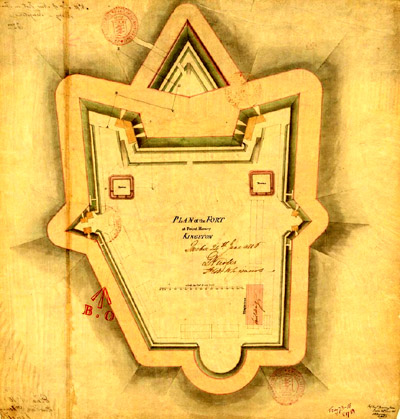

A 1783 plan of Fort Hamilton, intended to be built where Fort Henry is today. |

|

Following the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), the settlement that had started under the doomed walls of Fort Frontenac blossomed, with large numbers of ejected Loyalist Americans being resettled there. The town was officially renamed Kingston in 1788, and spent the next several decades as an important post of the British Empire, halfway betwixt Toronto and Montreal, a spot where Great Britain could keep a flinty eye on the doings of the dastardly Americans.

The British did a little work on rebuilding Fort Frontenac, but determined that the location sucked and would be difficult to defend no matter how awesome of a starfort sat there, so they turned their gaze to Henry Point.

One of two spits of land that jut their way into the start of the Saint Lawrence River at Kingston (the other being Point Frederick, home to yet another fort, creatively named Fort Frederick), Henry Point was a perfect location for fortification.

|

|

The Saint Lawrence River connects the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean, swinging through Montreal and Quebec City, so one can imagine how important this waterway was to everybody in the northeast at the time. And the Rideau Canal, which connects Ottowa with Lake Ontario, also meets that lake at Kingston. 'Twas so important indeed that, at the start of the War of 1812 (1812-1815) the British had their Lake Ontario naval squadron based on Frederick Point at Kingston, while America had theirs just slightly to the southwest at Sackets Harbor.

|

Though the Royal Navy base at Kingston played an important role, the War of 1812 (1812-1815) somehow didn't include an attack on the town. This was fortuitous in that the first iteration of Fort Henry, named for previous Royal Governor of Quebec, Henry Hamilton (1734-1796), started in 1813, wasn't completed until 1816. This fort had walls made of earth and stone, as well as magazines, barracks, signal towers and a few supporting gun batteries.

But it must have sucked to some degree, because the British tore the first Fort Henry down in 1832 and began construction of the real Fort Henry. This was a rather undignified hexagon, vaguely similar to Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. What makes Fort Henry interesting, at least to me, is its Advanced Battery, which is the part jutting aggressively downward, daggerlike.

|

|

A touristy map of the fort today. "Pubic Washrooms." Oh, Canada. |

|

The Advanced Battery was added in 1842, as Fort Henry's first line of defense: Perhaps someone finally noticed that their new fort had no bastions for heavens' sake, so how precisely would it be defended against attacking infantry?!

Further development was planned, but cost overruns with the Rideau Canal sucked up available funds, and so all that was added to Fort Henry were four of those ridiculous Martello Towers, cheap 'n' dumb. The fort's Advanced Battery was also connected to the main fort during this period, however, with a stout series of casemated rooms. This created a new kind of fort, which shall heretofore be known as the stabbyfort.

|

| One of Fort Henry's attendant Martello Towers: Cheap 'n' dumb. |

|

Imperial (British) troops garrisoned Fort Henry from 1813. Improving relations with the United States made a fort at Kingston somewhat superfluous, but a fort is always an excellent place to imprison people if you're not using it for anything else, so prisoners from Canada's 1837-38 Rebellions were kept there.

The Federal Dominion of Canada was declared on July 1, 1867, making Canada a somewhat, kind of, partially independent-from-Great Britain nation, if you don't mind us being so bold as to thus state. Fort Henry continued to be garrisoned by British troops until 1870, whereupon Canadian troops took over the arduous duty of garrisoning a fort that was in absolutely no danger of being attacked by anyone, until 1891.

Fort Henry was left to the elements for a couple of decades, but then proved its worth again during the First World War (1914-1918), as a secure facility at which to imprison any German, Austrian and Turkish (and even some Ukranian) civilians who were unfortunate enough to find themselves in Canada. |

|

The fort was opened to then public as an historic site and museum in 1938, but was drafted back into service at the start of the Second World War (1939-1945) as Camp 31, a POW camp for captured German Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine personnel. Once that unpleasantness was out of the way, Fort Henry reopened as a museum in 1948.

|

Today Fort Henry exists as a living museum, entertainingly manned by the Fort Henry Guard. Founded in 1938, the Guard is a reenactment organization which recreates the British military dress and drill of 1867.

Fort Henry was included in Canada's first Forts Across Canada series of postage stamps, released in 1983. Don't bother sending them to me for Canada Day, because I already have them. But thank you for thinking of me. |

|

The Fort Henry Guard, resplendent in their Victorian British uniforms, utilize a most magnificent light source. |

|

Not a whole lot of Fort Frontenac is left for satellites to see! Not a whole lot of Fort Frontenac is left for satellites to see! |

|

...was built by the French in 1673 to protect their fur trading post at the mouth of the Cataraqui River. Originally known as Fort Cataraqui, it was later named after Louis de Buade de Frontenac (1622-1698), Governor of New France from 1672 to 1682, and then from 1689 until his death in 1698: Frontenac was responsible for the construction of the fort, so it does seem reasonable that it should be named after him, n'est pas?

The initial version of the Fort Frontanac was built of wood and earth, but in 1675 most of the fort was rebuilt out of stone, its walls three feet thick and twelve feet high, with a fifteen-foot ditch all the way around.

In 1687, the Marquis de Denonville (1637-1710) set the wheels in motion that all but destroyed Fort Frontenac before the British could even get involved. |

|

Fort Frontenac in happier times. When it existed. Fort Frontenac in happier times. When it existed. |

|

Denonville, New France's Governor General from 1685 to 1689, lured 50 Iroquois bigwigs to Fort Frontenac under a flag of truce, clapped them in irons and shipped them off to Marseilles, France, to serve as "galley slaves." At the very least, one hopes that the Iroquois got to spend some quality starfort time imprisoned at the vaguely starfortish Chateau d'If during their time in Marseilles. Denonville and his army then scampered off and attacked the Seneca Indians. |

|

Frontenac in his current form, in Ottowa. |

|

Perhaps predictably displeased by Denonville's duplicity, the Iroquois attacked a number of French settlements in retaliation, including Fort Frontenac, which they besieged for two months in 1688. Though the Iroquois were unable to destroy the fort itself, the settlement was devastated, and many of the fort's defenders died of scurvy. Fort Frontenac was knocked down abandoned by the French, who felt that its remote location was too difficult to defend.

|

And then they changed their minds! The French moved back in and rebuilt Fort Frontenac in 1695, using it as a base from whence to hack at the Iroquois.

Much effort was poured into Fort Frontenac in the 1740's, with the British proving to be an ever-increasing threat. The fort was expanded in size, guns and garrison, but over the next few years the focus of conflict swung away from Fort Frontenac. By the 1750's the fort was little more than a supply depot for the French Navy.

Happily, the Seven Years' War (1754-1763) boosted Fort Frontenac's ego and made it feel important again.

|

|

What's left of Fort Frontenac today: Little. |

|

In August of 1756, French troops under the Marquis de Montcalm (1712-1759) used Fort Frontenac as a staging area for an attack on the British at Fort Ontario in Oswego, New York. This attack was a resounding success, indeed one of France's few big victories of the war...it also led to Fort Frontenac's destruction. Again, but this time at the hands of the British, who arrived at the fort in August of 1758 with 3000 men under the command of Lieutenant Colonel John Bradstreet (1714-1774). Fort Frontenac's 110 defenders surrendered and were allowed to leave unmolested. But leave they did, and this time the French were never to return. At this point you may return to the third paragraph on this page, where the history of Kingston continues. If so inclined, you could continue reading the whole page over and over until the Zombie Apocalypse, Global EMP Strike or whatever turns off all the world's electricity. Because one of those things is coming, and y'know where you would be the safest in such a situation? Inside a starfort.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|