|

Fort Thüngen

...and the story of the late, great Fortress Luxembourg

Luxembourg City, Luxembourg

|

|

|

Constructed: 1732-1733,

1836-1860, 1990's

Used by: Austria, France, Prussia

Conflicts in which it participated:

None

|

Through much of the Middle Ages and into the 19th century, teeny Luxembourg played a much more substantial role in Europe than those squinting at it on a map of the continent today might suspect. Count Henry of Luxembourg (1273-1313) became Holy Roman Emperor in 1312, and the House of Luxembourg would produce three more such Holy Emperors.

But it was the wee duchy's location, betwixt France, Germany and what in the 16th 'n' 17th centuries was the Spanish Netherlands, that made it so important in the age of the starfort. Luxembourg City was established in the 10th century, perched atop cliffs overlooking the confluence of the Alzette and Pétrusse rivers.

|

|

|

|

The Romans were (of course) the first to build walls around the town, and after the standard, centuries-long period of everybody staring blankly at the crumbling walls after the Romans left, Luxembourg City's walls were upgraded in the 14th century. A Burgundian army led by Philip the Good (1396-1467) took the fortified city "by surprise" in 1443. Two years prior, Philip had made an arrangement with Luxembourg's erstwhile owner, Elisabeth of Görlitz (1390-1451) for eventual possession of the Duchy, but it would appear that Philip the Good was also Philip the Impatient (studio audience laughs here).

|

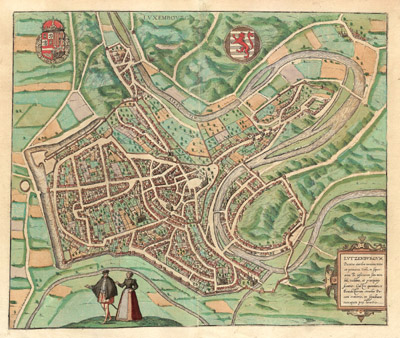

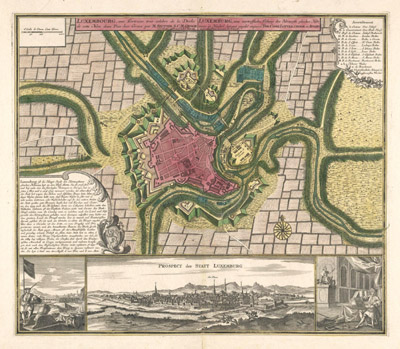

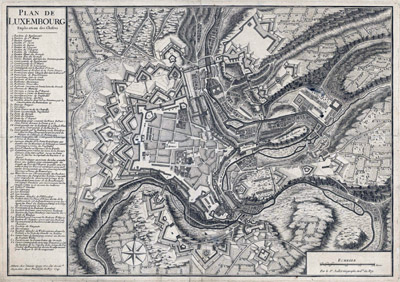

Three stages of Luxembourg City's starfort development:

Luxembourg City in 1600, already with some starfortish qualities. Luxembourg City in 1600, already with some starfortish qualities.

The city after Vauban got done with it, around 1700.

Austrian additions, built in the 1730's. What does not appear on this last map, inexplicably, is Fort Thüngen, which was in existence in 1741, the year that this map is dated...it was right there in the center of the three outerworks extending out to the city's east & northeast. There's a good chance that the Fort Thüngen that the Austrians built didn't look much like the Fort Thüngen we see today, which was modeled after the Prussians' version of the fort. Or maybe the cartographer just ignored Fort Thüngen because he was drinking, and had grown weary of representing each and every aspect of the city's fortifications. You had one job, cartographer. |

|

Luxembourg City received its first starfortilogical elements in the mid-1540's, when Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (1500-1558) hired some Dutch and Italian engineers and turned them loose on the city. They built Luxembourg's first pointy bastions linked with curtain walls, which is essentially what makes a starfort, now isn't it.

A hundred years later, Spain was running the show in Luxembourg, and added their own flair to the fortificational proceedings. A proven tactic of siege warfare in this period was mining, in which an attacking army would endeavor to dig tunnels beneath the defender's walls, place explosives accordingly and hope to force a gap in those walls...while the defenders would be furiously digging countermines, intended to disrupt the attackers' dastardly plans. This sort of enterprise was unlikely to have been much of a factor in Luxembourg City's case, built as it was atop a granite mountain, but any serious army of the 17th century had engineers-a-plenty whose expertise was in mining, and Spain put their engineers to work digging out 14 miles of tunnels under the works of Luxembourg City, as well as the construction of many casemates.

Tunnels weren't only useful for mining of course, and in this case would have been used for communication, storage, troop movement and as a place to hunker down during notional bombardment.

The Spanish Chief Engineer, Louvigny, also extended a second line of defense around the city, and reasoned that further fortification should be constructed on the far sides of the Pétrusse and Alzette River valleys, facing the city...but King Charles wasn't willing to completely empty Spain's treasury for Luxembourg City's fortifications, so the funds for such expensive works weren't made available.

I can't count the number of times I have thought, thank goodness for Vauban. Because in addition to being the Father of the Starfort, he was also the world's leading expert on siegecraft: To know how to build 'em, ya gotta know how to defeat 'em, and Vauban was a master of both ends of this spectrum. With the assistance of Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban (1633-1707), the French army staged a successful siege of Luxembourg City as part of the War of the Reunions (1683-1684), and into that city he marched immediately thereafter, rubbing his hands together in anticipatory glee...because France's King Louis XIV (1638-1715) had way more money to throw around than had that poverty-stricken loser Charles V. |

|

Louvigny's dream of fortifying the heights around Luxembourg City were belatedly realized thanks to Vauban, and a multitude of other outerworks were built during this period of French largesse. Sadly, all of the fortification in the world couldn't defend the city from being traded away in treaty negotiations. The Peace of Ryswick (1697) concluded the Nine Years' War (1688-1697...doing the math real quick...yep, that's nine years!), in which France fought against the Grand Alliance (which was constituted of pretty much the rest of Europe)...and one stipulation of this treaty was that Luxembourg City was to be given back to Spain.

|

But, Fortress Luxembourg being the most expensively-fortified ping-pong ball in history, administration of the city was handed back over to the French in 1701, at the outset of the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714)...The Treaty of Utrecht (1713), however, handed our city over to the Dutch, who were almost instantly displaced, peacefully, by the Austrians in 1715.

Over the next 80 years, Austria added several exterior forts, mostly to the city's east. They also effectively closed off the valley with a lock system, conrolling the flow of the Pétrusse and Alzette Rivers. Previously undisturbed rock was somehow found in the city (how could anything have been undisturbed in that relatively small city after all of this fortification?!), and more casemates were dug.

|

|

Some of Fortress Luxembourg's elements are still in place today, such as these two bastions along the southern side of the city, which I will cautiously identify as Bastion de Begue (the big one, further away) and an unnamed, detached bastion "whose fire decreases by the construction of Batardeau 19," whatever that means...although Batardeau 19 would make an awesome album title. Some of Fortress Luxembourg's elements are still in place today, such as these two bastions along the southern side of the city, which I will cautiously identify as Bastion de Begue (the big one, further away) and an unnamed, detached bastion "whose fire decreases by the construction of Batardeau 19," whatever that means...although Batardeau 19 would make an awesome album title. |

|

One very small part of the Austrians' additions to Fortress Luxembourg was the adorable little arrowfort at the top of this page: Fort Thüngen. Our fort was named for Oberstfeldwachtmeister Adam Sigismund von Thüngen (1687-1745), the latest in a long line of von Thüngens dating back to the 8th century: Thüngen means, of course, "thing," in this case referring to a governing body in early Germanic society (also known as a folkmoot). Thüngen was, and continues to be, a market town in Bavaria.

Fort Thüngen (or perhaps Fort Folkmoot) was built as an extension of Fort Grünewald, one of the many outerworks that the Austrians had added to Fortress Luxembourg. Located on one of the highest points of the city, the spot where Fort Thüngen would be built had previously been occupied by a observation post, placed there by Vauban.

Fort Thüngen was armed with ten guns in casemates and sprouted a dizzying array of underground galleries and "mine chambers," but its most noteworthy elements were the Dräi Eechelen, "three acorns." Three crenellated towers comprise the end of Fort Thüngen that faces back towards the city, each topped with a lovely, stylized acorn finial. Why acorns? Who knows, but we do know that it was the Prussians who planted those weird acorns, when they upgraded Fort Thüngen in the 1830's. As small and relatively insignificant a part of Fortress Luxembourg as was Fort Thüngen, it illustrates how much care and effort the Austrians and Prussians put into every single aspect of Fortress Luxembourg.

|

Prior to Fort Thüngen's 1990 restoration, the remains of a big redoubt, called Parc, was still visible in front of our fort. Today that spot is occupied by Luxembourg's Museum of Modern Art. Prior to Fort Thüngen's 1990 restoration, the remains of a big redoubt, called Parc, was still visible in front of our fort. Today that spot is occupied by Luxembourg's Museum of Modern Art. |

|

And then, along came the French Revolution. Good old France reobtained Fortress Luxembourg following an 11-month blockade in 1795...but, perhaps otherwise occupied with being at war with the entire world, France did not substantially enhance the city's defenses during their period of occupation. How could they? What further avenues of fortification were left, other than completely sealing the city under a hermetically sealed, bulletproof glass bowl?

When Napoleon (1769-1821) was finally locked away for good in 1815, Luxembourg the country was handed over to the German Confederation (which mostly meant Prussia), while simultaneously being in a "personal union" with the King of the Netherlands. |

|

Meanwhile, Fortress Luxembourg was made a "federal fortress," to be jointly manned by both of Luxembourg's new ruling parties, at a ratio of 25% Dutch, 75% Prussian. As oddly tortured as this logic seems today, these decisions were made at the Congress of Vienna (1814-1815), which international body had the thankless task of trying to reassemble everything in Europe that Napoleon had broken during his reign, which just about was everything, so perhaps we'll excuse them for a few questionable rulings.

Naturally, the Prussians elbowed the Dutch out of Fortress Luxembourg in short order, and garrisoned the living heck out of the place...by the 1860's, there were 4,000 Prussian troops, in a city of 10,000 residents. One might reasonably wonder how those residents felt about all of this international flip-floppery? Imagine just trying to live your life in a city which, thanks to the massive fortificational efforts of virtually all of Europe's great powers, has become such a strategic pawn (more like a rook, I guess) that no power could afford to allow any other power to possess it.

|

Which is to say that the city's residents were not crazy about the situation, particularly when the Prussians got super-militant about the city's defenses. The price of achieving the level of defensive fortification that the Prussians attained was that every square inch of space in and immediately around the city were taken up for martial purposes.

This meant that all of the nearby land that had been producing food for the city was no longer available for such pedestrian efforts. There's a story of three young women whose only source of income was an apple orchard outside the city's walls, which orchard the Prussians did away with in order to make way for the third line of defenses they were now erecting around the city: When the women attempted to collect the apples fallen from the downed trees by way of small recompense, the Prussians chased them away. Which may or may not have actually occurred, but it sure sounds like the Prussians, doesn't it?

But those Prussians weren't the only meanies who made the residents of Luxembourg City miserable: The Spanish, Austrians and French had all vastly overpopulated the city when they manned the Fortress, frequently billeting themselves amongst the already-crowded populace. When the Austrians feared a French attack on the city at the end of the 1720's, for example, they shoehorned 10,000 troops in amongst a civilian population of 8,000.

In 1866 the Holy Roman Empire wheezed its final, belabored breath in the form of the Austro-Prussian War. Prussia's victory paved the way for the unification of the northern German states, which didn't include Luxembourg. The Dutch still technically owned Luxembourg, but Prussian troops continued to garrison the Fortress of our present interest. And whom would choose this moment to further complicate things? Why, that would be Napoleon III (1808-1873).

|

|

There's your dräi Eechelen! There's your dräi Eechelen! |

|

Prior to his undignified defeat and incarceration at the hands of the Franco-Prussian War (1871)'s victors, France's Napoleon III did his best to unsettle Europe by way of throwing his weight around, significant harrumphing and quasi-threatening behavior. When he offered the Netherlands' King William III (1817-1890) five million guilder for Luxembourg in 1867, however, it precipitated the Luxembourg Crisis: The precious balance of power in Europe was threatened (or at least Prussia was threatened) enough that an international body stepped in. Austria, Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, Prussia, the United Kingdom and for some reason Russia, all signed the Treaty of London in 1867.

Fort Thüngen in relation to Fort Obergrünewald, a Vauban addition that the Austrians improved to enhance the city's eastern approaches.

This treaty declared that Luxembourg would remain a neutral state into perpetuity, and in order to make such a thing even possible, the mighty Fortress Luxembourg was to be dismantled...and just in time, because the Prussians had been planning a fourth line of defenses

, probably along the lines of those of Strasbourg: Numerous detached "artillery forts" surrounding the city some distance from the fortress itself. The universal reaction to the destroying-the-fortress part of the Treaty of London amongst Luxembourg City's residents was, hooraaaaay!, and, eager to avoid being the focal point of what appeared to be a looming war bewtixt France and Prussia, they enthusiastically participated in the dismantling process.

|

|

|

The orderly destruction of Fortress Luxembourg proceeded over the following fifteen years. Much of the cost of this demolition was borne by the city itself, with the proceeds from selling the land atop which the fortifications existed funding the project.

While the Treaty of London specifically demanded that the fortifications on the western side of the city be torn down, there was also plenty of impressive fortification on the eastern side, which was also expected to be rendered unusable for military purposes: This included the Grünewald Front, of which Fort Thüngen was a detached work. |

|

The demolition of Fort Thüngen got underway in 1870. The Dräi Eechelen, and the towers upon which they stand, were spared...but just about everything else was razed. A relaxing park was arranged on the grounds of the ex-fort which, this being the highest point in Luxembourg City, probably afforded breathtaking views of what was probably through the end of the 19th century a rather scarred city, what with all the recently-destroyed fortifications lying all over the place.

While Fortress Luxembourg's walls, bastions and towers were mostly done away with as per the Treaty of London, much of the network of underground tunnels, casemates and those mysterious "mine chambers" were left intact, because...well, nobody could see them, and they weren't hurting anybody, so why make the effort to fill them in? The passages that had been under Fort Thüngen were rediscovered in the 1980's, and by 1990 the site had been cleared of all that pesky vegetation, for study. Over the next few years Fort Thüngen was rebuilt to its most impressive Prussian-era state, and a museum dedicated to Fortress Luxembourg was opened therein, in the late 90's. Luxembourg's Museum of Modern Art, the Mudam, was built atop the trace of the detached bastion known as Parc that had once loomed so menacingly to Fort Thüngen's northeast at the same time.

Prior to 1867, in addition to the overwhelming arrangement of fortifications in and around Luxembourg City, fourteen detached works helped to secure the city from the ravages of whatever European power wasn't currently manning Fortress Luxembourg. Of those fourteen, today only Fort Thüngen remains.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|