|

Southsea Castle

Portsmouth, Hampshire, United Kingdom

|

|

|

Constructed: 1544, 1680's, 1814,

1850's, 1860's

Used by: England

Conflict in which it participated:

Battle of the Solent, English Civil War

|

Most heavily starforted nations have a distinct event in their history that prompted them to undertake the vastly expensive and time-consuming effort to fortify in an organized manner. The starfort was invented in Italy at the end of the 15th century, in response to a cannon-armed threat from France. In the United States, the bitter lessons learned in the War of 1812, specifically after the British marched into Washington, DC and burned down most of the governmental buildings, sparked a starfort-building bonanza.

|

|

|

|

England, however, can trace the beginning of its effort to join the ranks of starforted nations thanks to the wienergames of King Henry VIII (1491-1547). Henry had some physiological condition that prevented him from siring male children, which was important for the Tudor dynasty, because a male heir would be more likely to ascend to the throne of England without contest than would a female.

Henry went through six wives, all of whom seemed recalcitrantly determined to only provide him with females, and it was of course out of the question that Henry could have been the source of this tragic malelessness. Henry's determination to seek an annulment of his first marriage, to Catherine of Aragon (1485-1536), pissed off the Spanish, from whence Catherine had come; Pope Clement VII (1478-1534), who would not grant an annulment; and the rest of Catholicism, because Henry made himself the head of the Anglican Church so as to circumvent the Pope's decision. The expectation of bloodthirsty Catholic armies invading England and forcing Henry to stay married to these dumb women who refused to make boy babies for him, made this an excellent time to not only invest heavily in a Navy to keep those with ill intent off of the British isles, but to drag England into the era of modern fortification.

It is believed that Henry, perhaps familiar with the revolutionary writings of forward-thinking Italians such as Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472), played some role in the design of Southsea Castle, and that the starfort of our current interest may well be the first example of something reasonably resembling the trace Italienne in England.

|

Southsea Castle in its original form, in 1544. Painting by Alan Sorrell. Southsea Castle in its original form, in 1544. Painting by Alan Sorrell. |

|

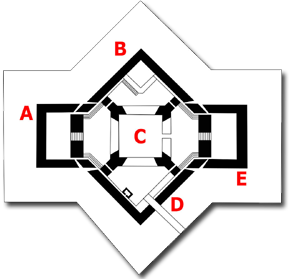

Southsea Castle, from a 1577 plan. A: East Gun Platform - B: South Bastion - C: Keep - D: North Bastion and Bridge - E: West Gun Platform Southsea Castle, from a 1577 plan. A: East Gun Platform - B: South Bastion - C: Keep - D: North Bastion and Bridge - E: West Gun Platform |

|

...not a terrible fort design for a monarch to produce, is it? The art of the starfort was still very much in development in the early 16th century, particularly in places other than Italy. Other schools of thought on how to best protect against, and support the use of artillery were being investigated: The rounded bastion was thought by many to be the best defense against cannon fire, and some of the fort designs in King Henry VIII's Device Programme utilized the rounded bastion concept: Deal Castle in Kent is a fine example of this phenomenon. Vague fears of Catholic invasion became a specific threat of a French attack in 1544, and Southsea Castle was built "in haste" in 1544, overlooking a deepwater channel in the Solent, which is the body of water that leads into Portsmouth Harbor. Portsmouth was a logical place to expect a French attack, as it was a) reasonably close to the French coast and b) home to Henry's burgeoning English Navy. When completed in October of 1544, Southsea Castle was manned by a whopping eight soldiers, twelve gunners and a porter...all commanded by John Chatterton, captain of the Portsmouth garrison. Our diminutive starfort was armed with seven brass artillery pieces and eight iron guns. |

The much-dreaded French invasion materialized on July 18, 1545, in the form of 30,000 men in 200 ships, which was a larger force than the Spanish Armada's attempted invasion of England 43 years later. Ultimately the French were only slightly more successful than the Spanish would later be, in that the French at least managed to get some troops ashore on the Isle of Wight, but much more photogenic (engravogenic?) was the Battle of the Solent.

Depicted in Cowdray's Engraving, the battle betwixt the French and English navies was inconclusive, but the French did eventually give up and go home, invasion incomplete. Most of the damage inflicted seems to have had more to do with both navies being unclear on how ships work, than actual enemy action.

|

|

The center of the Cowdray Engraving, depicting the Battle of the Solent, 1545. There's Southsea Castle playing its stellar role: Click on it to see the whole engraving, which is quite an impressive work! The center of the Cowdray Engraving, depicting the Battle of the Solent, 1545. There's Southsea Castle playing its stellar role: Click on it to see the whole engraving, which is quite an impressive work! |

|

The only real tragedy suffered by the English Navy in this debacle was the loss of Henry's beloved flagship, the Mary Rose: The reason for her loss with most of her crew is unknown, but there are suspicions that the crew neglected to close her lower gunports after firing, and she took on water when heeling over in a breeze. Ships are complicated. But most importantly for our story, King Henry VIII spent most of the battle watching the turn of events atop Southsea Castle!

Though nobody who was French approached Southsea Castle during this engagement, Henry nonetheless ordered additions to our little starfort the following summer: Stone "flankers," which were likely ravelinish entities built at a slight remove from the fort's walls, and a caponniere, which is always a wise attachment, were added.

|

|

Southsea Castle did not look like this during the English Civil War! Because this depicts our fort in 1760, over a century after that conflict...but everybody was so busy during the English Civil War, they didn't have time to sit around, drawing starforts. Southsea Castle did not look like this during the English Civil War! Because this depicts our fort in 1760, over a century after that conflict...but everybody was so busy during the English Civil War, they didn't have time to sit around, drawing starforts. |

|

Southsea Castle's only chance to directly defy an adversary came during the English Civil War (1642-1651). Both forces representing Parliament and those fighting for King Charles I (1600-1649) wanted Portsmouth (although one supposes that both sides wanted everything, which was kind of the whole point), and he who commanded Southsea Castle commanded the Solent...or, in this case, he who commanded Southsea Castle on behalf of the Royalists drank too darned much.

Not that drinking any less probably would have made much difference. Southsea Castle was armed with fourteen guns in September of 1642, but there were only twelve men garrisoning it, when 400 Parliamentarian troops surrounded our starfortlet.

|

|

Those outside Southsea Castle demanded the surrender of those inside, but the garrison's commanding officer, a Captain Chaloner, had been drinking and didn't feel up to making any decisions at the moment...might you come back in the morning, he wondered? No, we might not, decided the Parliamentarians, and 80 of them scaled Southsea Castle's walls. Once confronted with 80 guys huffing and puffing after having climbed into a starfort whilst wearing those silly iron helmets, the garrison peacefully surrendered.

When Portsmouth's Royalist Governor, George Goring (1608-1657), heard that Southsea Castle had been taken, he ordered the guns on the town's walls to fire at it, and our fortlet traded shots with the town's garrison...but cannon in those days were more ornamental noisemakers than anything else, and nothing much was damaged. Three days later, apparently having decided that Southsea Castle was impervious to cannon shot, the town of Portsmouth surrendered to Parliament.

|

Southsea Castle's firing platforms were enhanced in the mid-1660's, to strengthen them for bigger guns: A glacis, an earthen slope designed to deflect gunfire from a fort's walls on its landward side, was added around the same time.

Southsea Castle remained manned through lengthy periods of peace, when things got understandably lax. In 1759, when our fort was manned by the 72nd Regiment of Foot, soldiers' families lived in the fort with the men of the garrison, and for some reason they were permitted to cook food in the room above the powder magazine...with a floor made of wooden slats the only thing separating them. Embers from the cooking fire did what could be expected of them, falling through the floorboards into the fort's powder supply. The resulting explosion killed 17 men, women and children...and made quite a mess of the fort's east side.

|

|

Southsea Castle around 1850, prior to a major overhaul in the 1860's. A lighthouse spontaneously appeared in our fort in 1828! You need to keep your starforts weeded, lest lighthouses go springing up in them unbidden. Southsea Castle around 1850, prior to a major overhaul in the 1860's. A lighthouse spontaneously appeared in our fort in 1828! You need to keep your starforts weeded, lest lighthouses go springing up in them unbidden. |

|

Following this unfortunate event, Southsea Castle was permitted to slide into a sad state of decline. By 1785 it was manned by a single sergeant, with "three or four men selling casks of ale and cakes." Southsea Castle was in such bad shape that the authorities considered scrapping it altogether...but an unlikely savior made our singed little fort necessary again: Revolutionary France! Had France not gone collectively nuts in 1789, who knows what Europe and much of the rest of the world would have done with itself for the next 30 years! Certainly nothing as fun and productive as the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815). But even before Napoleon (1769-1821) burst onto the world stage, England had cause to fear yet another French invasion, so Southsea Castle was granted a new lease on life.

|

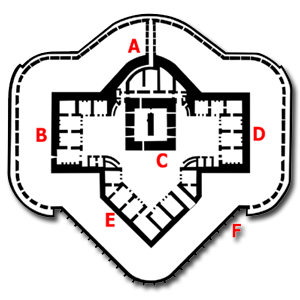

Our castle in 1834: A: South Bastion - B: East Platform - C: Keep - D: West Platform - E: North Bastion - F: Counterscarp Gallery Our castle in 1834: A: South Bastion - B: East Platform - C: Keep - D: West Platform - E: North Bastion - F: Counterscarp Gallery |

|

But seemingly nobody was in a tearing hurry, because the major improvements that Southsea Castle received didn't come about until 1813-1814, when the war with Napoleon was almost over. Our fort's north wall was knocked down and moved further out, making room for a larger garrison and a spacier gun deck atop: Guns just kept getting bigger and heavier!

A counterscarp gallery was also added during this period: A tunnel from inside the fort led to a firing gallery in the surrounding ditch, giving defenders the ability to slaughter whomsoever (probably Frenchmen) might foolishly wander into that ditch. A lighthouse was wisely built on Southsea Castle's western gun deck in 1828, and it was raised to reach its current height of 34 feet above the fort in 1854: This lighthouse remained in use until 2017.

Overcrowding in Portsmouth's civilian jails became a problem in the 1840's, and Southsea Castle was granted the enviable opportunity to imprison people. From 1844 to 1850 around 150 prisoners were held at our fort, under the supervision of an artillery sergeant, who also oversaw those dumb guns that were still lying around, taking up space that could be used to house more prisoners.

|

|

The 1860's brought with it renewed fears of French invasion because, while history today remembers Napoleon III (1808-1873) as an ineffectual twerp, his "Second French Empire" seemed pretty convincingly foreboding prior to his rash decision to take on Prussia in 1870. Britain's Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston (1784-1865), saw fit to launch a fortification program that made England's southern and western ports bristle with modern weaponry.

The technology of artillery, which had been improving steadily since its inception, advanced by leaps and bounds in the last half of the 19th century. If old forts such as Southsea Castle wished to remain relevant, huge batteries would need to be added outside the fort's walls...which is precisely what happened in the case of our wee starfort.

|

Batteries, along with underground magazines, were built on either side of Southsea Castle from 1863 to 1869, and were given the whimsical names of East- and West Auxilliary Batteries. The fort itself was used for spotting and rangefinding, and did not mount any guns at this time. By 1886, 25 rifled, muzzle-loading guns protected the Solent from Greater Southsea Castle...Which seemed great for a few years, until breechloading guns became all the rage in the 1890's, and Portsmouth Harbor didn't wish to be left out of the party with silly old muzzleloaders.

|

|

Southsea Castle and its West Auxilliary Battery, which was added in the 1860's. There was also an East Auxilliary Battery built at the same time, but it's not nearly as impressive to look at. Southsea Castle and its West Auxilliary Battery, which was added in the 1860's. There was also an East Auxilliary Battery built at the same time, but it's not nearly as impressive to look at. |

|

Southsea Castle's batteries were brought up to snuff with newer guns by 1899, and five, 6-pounder quick-firing guns with attendant searchlights were mounted as well, in response to the new threat of speedy little torpedo boats. Over the past couple hundred years, Southsea Castle had been joined in the defense of Portsmouth by such stellar starforts as Fort Monckton, across the Solent in Gosport, and Fort Cumberland, a bit to the east covering the entrance to nearby Langstone Harbor...all of which formed Fortress Portsmouth. A dizzying array of guns in various inches, centimeters and poundages poked aggressively from our fort's defenses, and after 100 years of relative peace (brushfire wars in distant colonies hardly counted as war, after all), Great Britain was hankerin' for another big military throwdown. Thankfully, European politics hadn't advanced as comprehensively as had the armaments industry by the start of the 20th century, so trouble was, as ever, brewin'. The shores of the British Isles mostly escaped direct contact with the enemy during the First World War (1914-1918), but healthy fears of invasion necessitated coastal readiness, and Southsea Castle was manned and ready for any German foolishness on the Solent. An anti-aircraft gun was mounted at the castle in case of Zeppelin raids, which seemed a distinct, if unrealized in the case of Portsmouth Harbor, possibility.

|

|

|

Southsea Castle had historically been separated from the town of Portsmouth by a wide marshy area, which had been filled in with prison labor in the 1840's: Much of that reclaimed land had been reserved for use in conjuction with the fort, but in 1922 the military sold much of it to the town of Portsmouth, which turned it into a public park. Our fortling became a tourist attraction, at which visitors gathered to cover their ears while the huge guns were exercised. In 1927 the West Auxilliary Battery's guns were removed.

|

|

As the focus had shifted from Southsea Castle itself to its extended batteries, the fort had been neglected. It was manned during the Second World War (1939-1945), armed with two pretty goshdarned big BL 9.2-inch Mark X guns, and served as the headquarters for Portsmouth's "Fixed Defences." Conditions in the fort were abysmal, described by one soldier stationed therein as "cold, wet and horrible." Welcome to seacoast defenses, sonny! Barrage balloons were strung up from the castle to defend it from air action, but it was hit with two incendiary bombs anyway, courtesy of the Luftwaffe: Little damage resulted.

|

When France fell to the Nazis in 1940, much of its Navy was at sea, and had no place to go, unless it wished to return to home ports and be commandeered by the Germans. On several unfortunate occasions, French Navy ships were fired upon and destroyed with great loss of life by Britain's Royal Navy, lest they fall into the clutches of the Kriegsmarine.

A few French Naval vessels puttered into Portsmouth Harbor in June of 1940, stayed for a while and then made as if to depart...which Great Britain could not permit.

|

|

|

|

One of Southsea Castle's guns was laid on the French Destroyer Léopard, which ship responded by aiming her guns at the fort...but there was no shooting, and on July 3, "Operation Catapult" was launched (get it?), in which British forces boarded and captured all French vessels in Portsmouth Harbor. The Léopard was turned over to the Free French Navy in August of 1940, and she spent the next few years escorting Allied convoys, until she ran aground off Benghazi in 1943, and came apart when the weather turned rough.

|

One of the guns on display today at Southsea Castle is this 68-pounder, muzzle-loader, dating to the 1840's. Photo by Rob Pennycook: Thanks, Rob! One of the guns on display today at Southsea Castle is this 68-pounder, muzzle-loader, dating to the 1840's. Photo by Rob Pennycook: Thanks, Rob! |

|

In 1960, the British military finally gave up on Southsea Castle, and sold it to Portsmouth City Council for £35,000. Over the next few years much of the additions made to the fort after 1816 or so were removed, returning it to a shiny state of Napoleonic War readiness. It opened as a museum in 1967, which role it still plays today.

A festive variety of historic cannon are on display in and around the fort, primarily from the exciting days of the 19th century. Southsea Castle is frequently rented for weddings, and there is reportedly a microbrewery operating in the fort, which is likely run by the ancestors of those guys who sold casks of ale and cakes from the fort in 1785!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|