|

Fuerte de San Pedro

Cebu City, Cebu, Philippines

|

|

|

Constructed: Completed in 1738(?)

Used by: Spain, USA, Japan, Philippines

Conflicts in which it participated:

Second World War, sort of

|

As far as we, the starfort enthusiasts are concerned, the Philippines leapt into existence in 1521 when Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan (1480-1521) showed up and claimed this archipelago for Spain. Upon deeper reflection Magellan may have elected to not discover the Philippines, as he was killed later that year at the Battle of Mactan (April 27, 1521)...but most of the pieces of his mangled corpse were duly loaded back onto his ship, aboard which his pieces completed the first circumnavigation of the earth, to his eternal (if unenjoyed) fame.

Being overwhelmed at Magellan's side was a force from the Rajahnate of Cebu. This was an entity created by exploratorive Indians in the 9th century AD, who were forever defending themselves against incursions of the Muslim Moros from the southern island of Mindanao...and who were currently in the process of being converted to Christianity, thanks to Magellan. |

|

|

|

Which process was violently completed by Conquistador Miguel López de Legazpi (1502-1572), when he dissolved the Rajahnate of Cebu in 1565. No room for alternate forms of government in the Spanish Empire, thank you very much! The Philippines had been so named in 1542 after Spain's King Phillip II (1527-1598), who likely asked, "...where exactly is this place?"

|

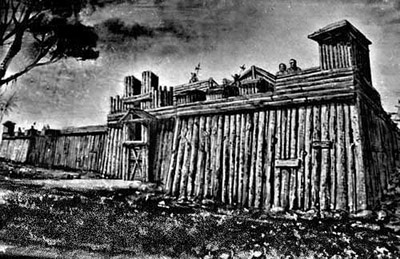

What the first Spanish fort at Cebu probably looked like. This is of course an artist's depiction, as all of the photography from the 16th century suffered from not existing yet. |

|

The Mighty Legazpi was also responsible for the first Spanish fortification in Cebu. Ground was broken for this endeavor in 1565, and the end result was likely a wooden monstrosity such as we see to the left.

Cebu City (the Spanish characteristically and ridiculously renamed it Villa del Santísimo Nombre de Jesús, "Town of the Most Holy Name of Jesus," but fortunately this name did not stick) would develop as Spain's first permanent colony in the Philippines. The actual date of the presently exiting Fuerte de San Pedro's construction is somewhat at issue.

|

|

|

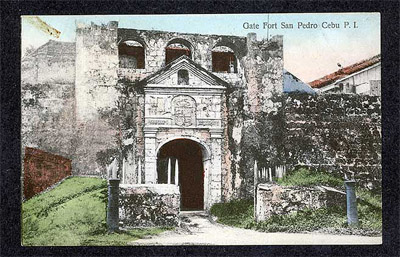

The stone fort may have been built as early as 1630, though date of 1738 is proudly emblazoned on the fuerte's gate, along with the standard-for-Spanish-starforts coat of arms of Spain's ruling house at the time, which in this case was Castille and Leon. The 1738 date may have had something to do with another King Philip, this one the V (1683-1746), inquiring about the state of defenses on the island of Cebu, which occurred in 1739.

The Philippine's Governor-General Tamón responded that the Fuerte de San Pedro was built of stone mortar, with a terreplein upon which guns were mounted. Its largest interior structure was the Cuerpo de Guardia, where the garrison lived. Outside the fort's walls was the Vivienda del Teniente, where its commanding officer was housed. There was a well in the fort, and its powder magazine was located in a structure attached to the northeast bastion, which was named San Miguel. Támon may have also added that the fuerte had just been completed in the previous year, whereupon his masons immediately started carving a "1738" over the gate, to make this statement true, lest the king somehow learn otherwise and lop off Támon's head.

|

England tended to name its starforts after potential royal sponsors in this period, hoping that royal person would be pleased that a fort in some far-flung place was named for him, and financially supporting the continued existence of said fort. The Spanish and Portuguese, meanwhile, named their forts for saints, assumedly in the hope that those saints would come back to life, gain lucrative employment, earn loads of money and then send it along for their namesake fort's upkeep. San Pedro was of course Apostle Peter, coolest of Jesus' apostles, and arguably the first Pope.

|

|

An 1899-ish postcard showing the Fuerte de San Pedro's gate. An 1899-ish postcard showing the Fuerte de San Pedro's gate. |

|

Being a Pope seems as though it would be relatively remunerative, but Peter was primarily a fisherman in his day, and it's unlikely that he could have financially supported the several forts that were named after him: The Castillo de San Pedro de la Roca in Santiago, Cuba, is another Pedroian example. It appears that life on Cebu wasn't any more arduous than anywhere else in the Philippines during Spain's 333-year administration. The Universidad de San Carlos was established there in 1595, and during the last half of the 19th century it seemed as though things were getting positively liberal: In 1860 Cebu opened its ports to foreign trade, its first independent printing house was established in 1873, and its first periodical, El Boletin de Cebú, was published in 1886. Could an independent Philippines be in the offing? Laughter, of course not.

|

A nice statue of Miguel López de Legazpi at the extent of Fuerte de San Pedro's northern bastion. At some sites this is identified as a statue of Ferdinand Magellan, but don't you believe it! Legazpi may have been a bit of a meanie, but he's the reason that this fuerte is where it is today. |

|

The reason that things were loosening up in the Philippines toward the end of the 19th century was that the Filipinos, along with much of the rest of Spain's colonies around the world, had been agitating to get rid of the Spanish for some time. Napoleon (1769-1821) had occupied Spain from 1808 to 1813, which left a lot of people in distant colonies blinking at one another in confusion. This was a major chink in Spain's armor, and many of the persons they had been subjugating for centuries recognized it as such. But when one empire dissolves a vacuum is formed, and in steps someone else with imperial ambitions. Enter the United States of America, stage right!

|

|

|

Filipino freedom fighters were overjoyed when the United States entered the fray against the wicked Spanish in 1898, and cheered when Commodore George Dewey (1837-1917)'s American fleet dispatched its Spanish counterpart with very little in the way of effort at the Battle of Manila Bay (May 1, 1898). Once the Spanish had been defeated on land as well, however, the Filipino expectation of independence was dealt a cruel blow. Spain surrendered Manila not to the Filipinos, but to US troops, who went to great lengths to keep Filipino forces out of that city.

|

After the initial rush of excitement and fulfillment, it turned out that the United States didn't much care for, and wasn't very good at, having a 19th century style empire. This didn't prevent the US from viciously fighting the Filipino independence movement that resumed resisting occupation once it was clear that the Americans didn't intend to leave. It also didn't prevent the US from officially occupying the Philippines from 1898 until 1946.

Like the rest of the Philippines, the island of Cebu became US territory in 1898, and was ruled by American governors until 1937. At that point it became a "charter territory," with local governance being handled by Filipinos.

|

|

Looking along what I will cautiously identify as the Fuerte de San Pedro's eastern wall towards its southeast bastion, on a lovely blue-sky Cebu City day. Looking along what I will cautiously identify as the Fuerte de San Pedro's eastern wall towards its southeast bastion, on a lovely blue-sky Cebu City day. |

|

Our fuerte became part of the US Army's Warwick Barracks, and from 1937 until 1941 was converted into a school, where many locals received their formal education. Things plodded along until the Second World War (1939-1945) brought Japanese soldiers to Cebu in August of 1942. The mighty United States had been vanquished, and Japan's slogan "Asia for the Asiatics" sounded just swell to many who had been fighting for Filipino independence...until it was made plain that a more accurate slogan would have been, "Asia for the Japanese, who are particularly cruel and murdery." The Philippines' American occupiers may have been clueless, inept and heavy-handed, but the Japanese were way worse. The Filipinos got back to resisting an occupier, in many cases led by American officers who had escaped the initial Japanese onslaught.

|

US troops from the Americal Division's 3rd Battalion, 132nd Infantry having a swell time on Talisay Beach, Cebu, on March 26, 1945. |

|

Cebu City wasn't always the placid safe haven for which the Japanese might have wished during their occupation. Japanese residents were occasionally forced to take refuge within the Fuerte de San Pedro.

US troops finally landed on Cebu in March of 1945 and, joined by 8,500 Cebuano guerillas, worked to cleanse the island of the Japanese, a goal which was achieved by the beginning of April. During the fracas many of the Japanese troops in Cebu City were forced into our fuerte for a period, during which the fort was used as an emergency hospital for the many wounded. All Japanese resistance on Cebu ended in July of 1945, and the war was over in August.

On July 4, 1946, the Philippines were finally recognized as an independent nation by the United States.

|

|

|

The Fuerte de San Pedro was utilized by the Philippine military as an "army camp" from 1946 until 1950, at which time somebody realized that starforts, as far as being active military installations, were so nineteenth (actually sixteenth) century. The Cebu Garden Club was put in charge of the fort, which they filled with lovely, colorful plant life. The Garden Club is also credited with repairing the fort's inner structures, which were used through the 1950's as offices for various Cebu City governmental entities.

|

In 1857, Cebu City's mayor, Sergio Osmeña Jr., announced that the Fuerte de San Pedro would be demolished, to be replaced with a new city hall. Mayor Osmeña was immediately hacked to death by enraged Cebuanos...or, if not actually hacked to death, was at least confronted by a great deal of public resistance to this plan. Bowing to public pressure, the mayor gave up his ludicrous idea and contented himself with building his dumb city hall on a space next to the fort.

That same year, a zoo was opened in the fort, weirdly operated by the Lamplighters, an obscure religious sect. By 1968 the lamplit animals had made a wreck of our fuerte, and plans to restore the fort got underway: Fortunately, relocating this strange religious zoo was job #1.

|

|

One of the Fuerte de San Pedro's remaining Spanish guns, mounted in what might not be the manner most efficacious for aiming. One of the Fuerte de San Pedro's remaining Spanish guns, mounted in what might not be the manner most efficacious for aiming. |

|

The fuerte's reconstruction was done right, with coral stones being brought in from the sea around Cebu, as the Spanish had originally done. Once the restoration of the fort's main building was completed, it opened as the Cebu Office of the Department of Tourism. Today the fort is operated by Cebu City, and houses a museum of artifacts from the Philippines' Spanish era.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|