|

Castillo San Felipe

Puerto Cabello, Venezuela

|

|

|

Constructed: 1732 - 1741

Used by: Spain, Venezuela

Also known as: Castillo Liberatador

Conflicts in which it participated:

Anti-Pirate Bashings

Anti-Colonial Bashings

Venezuelan Crisis of 1902-1903

|

Good ole Christopher Columbus (1450-1506) first spotted what is today Venezuela on his third voyage to the New World, in 1498. Chris sent such a glowing report of his discovery's beauty to Spanish monarchs Ferdinand (1452-1516) and Isabella (1451-1504) that Spain established its first permanent South American settlement at what is today the Venezuelan city of Cumaná, in 1522.

|

|

|

|

Venezuela was swiftly made a Spanish Province. In 1528, however, this province was officially turned over to a German banking family, the Welsers, as security for what must have been an enormous loan they had made to Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (1500-1558).

The Welsers developed the province as Klein-Venedig, or Little Venice, but were primarily interested in hunting for El Dorado, the fabled "Lost City of Gold." Virtually all of the Germans and African slaves who were shipped over to the New World for this pursuit died from tropical diseases or Indian attacks, and in 1546 Spain just decided "al diablo con este," executed the Welser representative in charge, defaulted on the loan and took the province back for themselves. This was not, however, the end of German financial interest in Venezuela.

Though Venezuela was a Spanish possession, it was difficult to keep the Dutch out of places they could reach by ship in the 17th century. As such, Puerto Cabello operated as a trading post for Dutch smugglers through much of the the 1600's.

|

|

|

Spain scoured Puerto Cabello of the Dutch in 1730, and began building a fort there to keep them out in 1732. The fort was named for Spain's King Phillip V (1683-1746)...as were a number of other Spanish forts built around this time, such as Fort San Felipe del Morro at San Juan, Puerto Rico, the Castillo de San Felipe in Ferrol, Spain, and Fort San Felipe on the Mississippi in Louisiana, near which Fort Jackson was built. |

|

The Castillo of our current interest was built to support the doings of the Guipuzcoana Company, a business endeavor created by the Spanish monarchy to dominate trade coming to and going from Venezuela. This concept proved violently unpopular not only with smugglers in the region but also the local populace, so much so that, the instant the Castillo San Felipe was completed in 1741, the Mutiny of San Felipe occurred. Whether this mutiny in any way invloved our Castillo is unclear, but about everybody who wasn't Spanish in Venezuela got rid of the Guipuzcoana Company for good.

A starfort was a useful thing to have handy, however, whether 'twas in direct support of a company or not, as the Caribbean was practically crawling with pirates, corsairs, privateers, filibusters, freebooters, and a dashing Errol Flynn (1909-1959). In 1742, British naval officer Sir Charles Knowles (1704-1777) was the first to attack the Castillo San Felipe, during the War of Jenkins' Ear (1739-1748, so named because it began with the dastardly amputation of a British sailor's ear (whose name was Jenkins) when the Spanish boarded his vessel). Knowles' activities on the coast of Venezuela were known ahead of time by the Spanish, who were able to gather a large force and be supplied with gunpowder by the Dutch (from whom the Spanish had violently taken Puerto Cabello a mere 12 years previously, but everybody hates the British), and the Castillo was able to deter Knowles' naval advances. Later in the year, the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) heated up, which drew everyone's attention to warrish activities in Europe, and nobody gave much of a hoot about the Castillo San Felipe any more.

|

The Castillo spent the next 70 years relatively unmolested, deterring pirates and their ilk from messing with Puerto Cabello. The Spanish Crown utilized the Castillo as a prison, jailing there such notables as Francisco de Miranda (1750-1816), a Venezuelan who had fought for America in the US Revolutionary War (1775-1783) and in the French Revolution (1789-1799), who had led a failed uprising in Venezuela against the Spanish.

Vicente Salias (1776-1814), author of the lyrics for Venezuela's national anthem, was executed at the Castillo San Felipe in 1814.

|

|

|

|

On June 30, 1812, an unlikely event took place in which the anti-Spanish prisoners in the Castillo San Felipe somehow sprung from their cells, armed themselves and, utilizing the fort's artillery, began firing upon the city of Puerto Cabello. Venezuela's First Republic had recently been declared, grandly stating independence from the Spanish Crown that was still very much in residence. This event proved to be one of the final acts of the First Republic, which was shortly defused by Royalists.

|

One of the Castillo's pointless yet vaguely attractive Guérites. The best thing to be said about these structures, over which Spanish, Portuguese and to a lesser extent Dutch starfort builders swooned in giddy adoration, is that they're invariably placed at a starfort's holiest spot: The bastion's leading edge. Click on it, it's huge. |

|

On June 24, 1821, the Spanish were finally beaten decisively at the Battle of Carabobo. On the road between Puerto Cabello and the town of Valencia, rebel troops led by the Godlike savior of South America, Simón Bolívar (1783-1830), routed the Royalists so definitively that only about 400 survivors out of the initial several thousand Royalist troops made it to the notional safety of the Castillo San Felipe. Those loyal to Spain huddled in the Castillo until November of 1821, when rebel troops finally took this last vestige of Spanish authority in Venezuela.

In most cases, this would be the end of the story of the Castillo San Felipe (which was by now also known as Castillo Liberatador, in homage to its role in the fall of the Spanish in Venezuela). By the last few decades of the 19th century, the starfort as a military defensive concept had been surpassed by the Artillery Fort and ever-progressing state of artillery itself. Just about every lovely starfort still standing around the world was being used as a prison, being expensively upgraded to mount modern guns (as was the case along the east coast of the US), or just left to rot.

Active investment in Venezuela by Germany, Italy and Great Britain through the 18th century, however, led to our Castillo being quite possibly the only target to ever be fired upon by both the British Royal Navy and Imperial German Navy simultaneously. I know, exciting, right?!

|

|

Venezuela dedicated the last decade of the 19th century to civil war, with lengthy periods of anarchy and no effective government. This sort of thing proved irksome to Germany, Great Britain and Italy, all of whom had substantial investments in Venezuela. Military strongman Cipriano Castro (1858-1924) siezed the Venezuelan presidency in October of 1899, and one of the first things he did once in power was default on all foreign debts.

The main reason Castro felt comfortable thumbing his nose at the powers of Europe was the Monroe Doctrine. Introduced as US policy in 1823 by President James Monroe (1758-1831), the Doctrine was intended to put a stop to further European colonization in the Western Hemisphere, though not to interfere with any colonies already in place. As such, when British and German warships were dispatched to Venezuela to blockade the offending ports, they did so having already assured US president Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) that there would be no invading, land grabbing or anything beyond attempts to force Castro into reconsidering his position. As Vice President in 1901, Roosevelt had said that "if any South American country misbehaves toward any European country, let the European country spank it." Way to uphold that Monroe Doctrine there, Teddy.

To be fair to the Tedster, allowing European powers to do just about anything in the Western Hemisphere, other than invade stuff, was perfectly in line with the original intent of the Monroe Doctrine. Plus, following the Venezuelan Crisis of 1902-1903, the Roosevelt Corollary of 1904 was added to the Monroe Doctrine, stating that the US had the right to intervene in Latin America in cases of "flagrant and chronic wrongdoing by a Latin American Nation." This vague wording led to a fun century of the US acting as the Western Hemispheric Police Force in such places as Nicaragua, Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Mexico.

|

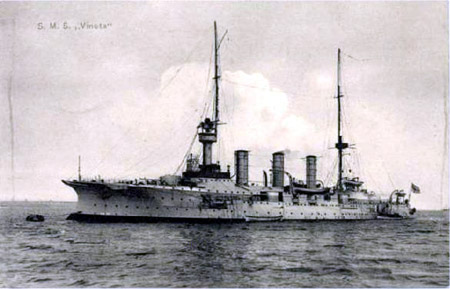

At the beginning of December 1902, Germany, Great Britain and soon Italy sent warships to blockade Venezuelan ports, and the majority of the Venezuelan navy was captured and/or sunk within a couple of days. Castro ordered the arrest of several hundred German and British civilians in Venezuela, and when he ignored the German and British governments' demands that these prisoners be released, the SMS Vineta of the Imperial German Navy and HMS Charybdis, a protected cruiser of the British Royal Navy launched in 1893, were dispatched to Puerto Cabello.

|

|

The SMS Vineta, a protected cruiser of the Imperial German Navy, built in 1895. The protected cruiser was one of the first classes of warships to sport an armored deck, intended to protect the ship's innards from plunging fire. |

|

The Castillo San Felipe and Puerto Cabello were bombarded by the Vineta and Charybdis, possibly the only occasion that Germany and Great Britain worked together to destroy something! There was a weird international effort to quell the Boxer Rebellion in China in 1900 that included both German and British troops, but somehow the German and British navies operating together seems particularly...wrong.

As the European blockade of Venezuelan ports ground on, public opinion in both the US and Great Britain became increasingly hostile regarding this effort. US President Roosevelt suggested that the conflicting parties enter into arbitration to settle their differences, and casually mentioned that the US Fleet, commanded by George Dewey (1837-1917), was conveniently placed at Puerto Rico, close enough to Venezuelan waters to affect the outcome of this conflict to the detriment of the European powers if he so chose.

Dewey's US Fleet was the one that had recently made the Spanish navy look absolutely ridiculous in the Spanish-American War (1898), and while the German and British navies would have doubtless proven a much more worthy adversary, the elements that were currently in the Caribbean would have been hopelessly outnumbered had Roosevelt turned Dewey loose on them. Though a tantalizingly delightful alternate history to consider, the US did not go to war with Germany and Britain over Venezuela.

By February of 1903, the European warships had steamed away, and Castro had pledged 30% of Venezuela's customs income to repaying the debts. Five years later Castro managed to piss off the Dutch in much the same way he had angered the rest of Europe five years earlier, and Venezuela's tiny navy was swiftly destroyed once again.

The Castillo San Felipe spent the next several decades as a prison, housing a veritable Who's Who of Venezuelan men I've never heard of. Today it is inaccessible to visitors, as it is part of the Augustín Armario Naval Base. Augustín Armario (1783-1833) was an Admiral of the Venezuelan Navy and hero of the independence movement, who was born in Puerto Cabello.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|