|

Castillo San Cristóbal

San Juan, Puerto Rico

|

|

|

Constructed:1766-1783

Used by: Spain,

United States

Conflicts in which it participated:

Anglo-Spanish War of 1796-1808,

Spanish-American War

|

Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) arrived at what would become Puerto Rico in November of 1493: The nursery rhyme about Columbus' second voyage (In fourteen hundred and ninety three, Columbus really had to pee) never caught on the way the rhyme about his first voyage did. |

|

|

|

Columbus came armed with a letter from Spain's King Ferdinand II (1452-1516), in which His Majesty decreed that a papal bull authorized the bearer of this letter to expand the Spanish Empire and Christian Faith, by any means he felt necessary. The island's natives, the Taíno, were duly impressed: "The King's signature and a papal bull!? Good God sir, please destroy us and our entire culture immediately!" And so it was.

Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de Léon (1474-1521) showed up in August of 1508 and made a settlement at a lovely natural harbor on the north side of the island, which he named Caparra. The name Puerto Rico, "Rich Port," was soon used to describe Ponce de Léon's settlement. By the mid-18th century the whole island was also known as Puerto Rico, so the city was Puerto Rico of Puerto Rico. Eventually, someone smacked himself in the forehead and renamed the city San Juan.

|

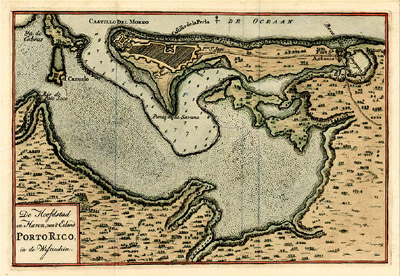

A Dutch map from 1766 reveals San Juan to be well-starforted! The Castillo of our current interest is listed here as the Castillo de la Perla, and a Fort St. Antonio guards El Boquéron, the waterway that swoops around the east of San Juan. And then of course there's the good ole Castillo del Morro. Were these fort names all correct at the time, or were the Dutch just misinformed about 2/3 of them? A Dutch map from 1766 reveals San Juan to be well-starforted! The Castillo of our current interest is listed here as the Castillo de la Perla, and a Fort St. Antonio guards El Boquéron, the waterway that swoops around the east of San Juan. And then of course there's the good ole Castillo del Morro. Were these fort names all correct at the time, or were the Dutch just misinformed about 2/3 of them? |

|

Spain was not, however, the only European power interested in harvesting the New World's riches. England and the Netherlands, in particular, took issue with Spain's position at San Juan, and conducted raids on a regular basis. Spain's King Charles V (1500-1598) ordered the construction of a fortification to defend his rico puerto in 1539, and by 1587 the really quite spectacular Castillo San Felipe del Morro was on duty, repelling the vast majority of Dutch and English thrusts. Some of the attacks on San Juan, while ultimately unsuccessful, wreaked havoc and caused damage to Spain's valuable colony. Further fortification is always the solution! While the Castillo del Morro was a formidable edifice, it was positioned to deter ships from approaching the main channel into the Bajo Trablazo, not to defend the city itself. |

|

|

In 1634 the Spanish built a small artillery redoubt, Fortín del Espigón, atop a hill called San Cristóbal (named for Saint Christopher, the patron saint of travelers...fitting for a hill at a far-flung outpost of the Spanish Empire), at the city's eastern extent: This was deemed necessary after the Dutch attacked from the city's landward side in 1625, a situation the vast Castillo del Morro was powerless to influence. Further fortification commenced in 1766, which lengthy process produced the Castillo San Cristóbal. Our Castillo is described as the largest colonial fortification built in the Americas, and while we often point out that the promoters of lots of forts claim such definitive titles, the Castillo San Cristóbal may well be the definite article! The Castillo we see at the top of this page is but the tip o' the proverbial iceberg: It's what was the citadel of the Castillo de San Cristóbal. The whole fort completely surrounded the city of Old San Juan!

Olde Towne San Juan, which is still surrounded by what's left of the Castillo de San Cristóbal. That's our present Castillo at top right, and the Castillo del Morro at top left. Cristóbal's enormous parade ground is just behind del Morro. Click the image, it's really quite large.

Built under the watchful eyes of Spanish Royal Engineers Tomás O'Daly (an Irish immigrant to Spain) and Juan Francisco Mestre, most of what we see of the Castillo was completed in 1783, though work on improvements would continue for another century. In all, the Castillo covered 27 acres, and included a vast parade ground, several casemates, and an intricate tunnel system, which included underground living quarters, powder magazines and sapper tunnels, which were positioned to be packed with explosives and blow up beneath any enemy that was so unwise as to besiege the city. Five cisterns, capable of holding over 700,000 gallons of water, would have been able to keep the Castillo (and presumably the city) supplied for a year.

|

One remnant of the 1634 fortification on San Cristóbal is la Garita del Diablo, the Devil's Guerite. Those who wish to learn more about guerites are encouraged to visit this site's Guerite page, but suffice it to say that a garita is a one-man sentry box, a holdover of the medieval bartizan, which occurred frequently on Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, and to a lesser extent English and French starforts. La Garita del Diablo is the most extended position of the Castillo, whence a sentry was expected to keep a sharp lookout for incoming danger from the sea...and naturally, a legend surrounds this garita.

|

|

La Garita del Diablo. Would the devil need a guerite? |

|

Local lore has it that sentries assigned (banished?) to this position tended to disappear without a trace. Further scrutiny of this story reveals that one sentry disappeared from la Garita del Diablo, a soldier by the name of Sánchez, who absconded from this post in order to escape with his girlfriend, Dina...but that is no kind of spooky legend. Today much of the Castillo is open to visitors, but la Garita is not...because everybody who gets within 30 feet of la garita disappears in a puff of yellow smoke!!! There, now that's a legend!

|

Arguably the real hero of the foiled British attack of 1797: The Fortín de San Gerónimo. Arguably the real hero of the foiled British attack of 1797: The Fortín de San Gerónimo. |

|

The thing that Spain was afraid would happen, happened in April of 1797: A ±10,000-man British force, led by Sir Ralph Abercromby (1734-1801), attacked San Juan. Flushed with victory after capturing the Spanish-owned island of Trinidad, the red-coated attackers outnumbered San Juan's defenders by around three to one...but the city's painstakingly crafted defenses saved the day for the Spanish.

The British were held at the southeastern extent of San Juan's fortifications, which were pounded for two weeks by the Royal Navy's guns: Little Fortín de San Gerónimo was at that corner about a mile from the Castillo San Cristóbal, and was constantly shored up with sandbags as it continued to fire on the invaders. |

|

|

Spanish domination was getting pretty long in the tooth by the middle of the 19th century, and there had been a series of rebellions, particularly following the post-Napoleonic Wars colonial shakeups of the 1820's. 1855 saw the rebellion of the Castillo San Cristóbal's native-born artillery brigade. The rebels held the Castillo for all of 24 hours, threateningly turning its guns to point at the city. Whether by bloody recapture or the rebels' peaceful surrender after a single day of being in charge, control of the Castillo was swiftly returned to its creators.

|

Since its creation, entrance into the Castillo San Cristóbal was gained through the gates at San Juan's docks, which were protected by the Ravelin de Santiago and Bastion de Santiago. By the end of the 19th century, the free flow of the growing city's traffic was determined to be more important than the continued 18th century-style defense of the fort's back door, and the ravelin and bastion were dynamited. Is it mere coincidence that, just a year following this severe fortificational adjustment, Spain's domination of Puerto Rico came to an end?

|

|

The Castillo San Cristóbal is a big ole lump of mean. Spain somehow managed to build their starforts ugly and beautiful at the same time! The Castillo San Cristóbal is a big ole lump of mean. Spain somehow managed to build their starforts ugly and beautiful at the same time! |

|

Why, yes. The Spanish-American War came in 1898, and no amount of Vaubannian enterprise would have kept the modern US Navy out. Captain Ángel Rivero Méndez (1856-1930) commanded the Castillo San Cristóbal on May 10, 1898, when the US Navy Auxilliary Cruiser USS Yale poked into San Juan Harbor. Méndez ordered one of his batteries, armed with modern but ineffectual Ordóñez Guns, to open fire on the Yale: Both shots fell short, but they were the first shots fired at US forces in Puerto Rico.

|

Today three flags fly o'er the Castillo San Cristóbal: That of Bourbon Spain, Puerto Rico and the United States. I would like to believe that the bulbous structure in the foreground is the entrance to the steps that lead to la Garita del Diablo, but as it appears to be on the city side of the fort, this seems unlikely. Today three flags fly o'er the Castillo San Cristóbal: That of Bourbon Spain, Puerto Rico and the United States. I would like to believe that the bulbous structure in the foreground is the entrance to the steps that lead to la Garita del Diablo, but as it appears to be on the city side of the fort, this seems unlikely. |

|

Many of San Juan's residents blamed Méndez for the destruction that rained down on them as a result of opening fire on the US Navy: The day-long artillery exchange betwixt the Navy and the Castillo didn't do the town any good...but he was issued the coveted (and characteristically windily titled) Cruz de la Orden del Mérito Militar 1ra Clase con Distintivo Rojo by the Spanish government, so somebody thought Méndez had done the right thing.

Six months later, the war lost, Méndez was ordered to turn over the keys to all of San Juan's defenses to the US Army. He was offered a commission in the US Army, which he declined, and retired from the Spanish Army the following year.

|

|

|

Puerto Rico was now a "United States Unincorporated Organized Territory." The Castillo remained an active-duty military installation of the United States up through the Second World War (1939-1945), when concrete pillboxes ("coastal observation posts") and an underground bunker control station (presently used as the fort's Visitor's Center) were built. It cisterns were prepared to be used as fallout shelters, but the Imperial Japanese Navy never got around to attacking San Juan.

The San Juan National Historic Site, including all of Old San Juan, was established in 1949. The US military finally left San Juan's ancient defenses in 1961, and they became the responsibility of the US National Park Service.

|

|

A somewhat silly reworking of the Castillo San Cristóbal: 'Twas a starfort, well-meaning preservationists, not a medieval castle. A somewhat silly reworking of the Castillo San Cristóbal: 'Twas a starfort, well-meaning preservationists, not a medieval castle. |

|

Presently, visitors of the Castillo San Cristóbal can peruse the fort's tunnels, witness "old weapons shooting demonstrations" on every third Sunday of the month, view the city from the fort's highest point at the Caballero de San Miguel, and disappear in a puff of yellow smoke upon entering la Garita del Diablo. Well. Visitors can do most of those things. Many thanks to starfort enthusiast Nils Jergensen, who recently alerted us to a number of lovely starforts in the Caribbean...such as this one!

Two pix I wish I had taken myself...well, I guess I wish I had taken all of these pix myself. One day. Two pix I wish I had taken myself...well, I guess I wish I had taken all of these pix myself. One day. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|