|

Fuerte de Loreto

and

Fuerte de Guadalupe

Puebla, Mexico

|

|

|

Constructed:1815±

Used by: Spain, Mexico, United States

Conflicts in which it participated:

French Intervention in Mexico

|

It was at the city of Puebla that a Mexican force defeated a larger French force on May 5, 1862. This day is celebrated annually in Mexico with some school closures and such, but it's much more popular in the United States, as norteamericanos definitely need more excuses to drink beer. At the center of the famous battle (and the less-famous battle a year later, in which the scrappy, patriotic Mexicans did not defeat the wicked French) were the Fuertes of Loreto and Guadalupe. |

|

|

|

Puebla was established in 1531 by the Spanish, in the interest of having a waypoint settlement betwixt Mexico City, the capital of New Spain, and Veracruz, the port at which they arrived in Mexico. The Valley of Cuetlaxcoapan ("Where Serpents Change Their Skin"), in which Puebla was built, had been used by the Aztecs and other indigenous peoples for Flower Wars, a method by which young males could be sacrificed to their gods in an heroic fashion: Fighting it out in carefully organized battles. Had the Spanish been aware of this practice, one doubts it would have disuaded them from building where they built...although the more aggressive indigenous persons killing each other off probably would have worked well for Spanish colonial aims!

|

The fuertes as they lie. Fuerte de Loreto is to the left at the hill's northwestern extent, Guadalupe to the right, at the southeastern extent. While these two forts seem almost comically close to one another, they were intended to cover the town and the road from Veracruz to Mexico City, from either side of their hill. |

|

|

Sometime in the 17th century, a local individual claimed to have been saved from malicious lightning by the Virgin of Loreto, and a shrine was duly built on the hilltop spot where he insisted this magical event had occurred. It must have been a shrine of some substance, because over the next century and more it was used by the city of Puebla as a prison. A shrine was also built on a commanding spot at the other end of the hill in this period, likely due to some other, equally implausible event, and named for the Virgin of Guadalupe.

|

As tended to be the case when places were colonized by persons other than those whom originally existed there, the locals grew unhappy with Spanish domination, and the War of Mexican Independence (1808-1821) rolled slugglshly into being. Aware of Puebla's importance as a waypoint between Veracruz and Mexico City, the Spanish fortified the shrines of Loreto and Guadalupe around 1815.

As we will learn, the Fuerte de Guadalupe sustained heavy damage in a later conflict, so what's there now may not accurately represent its original form...but it's clearly the more starforty of the two fuertes of our present interest.

|

|

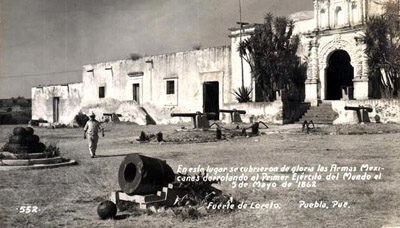

The Fuerte de Loreto at the moment of its conception in 1815: Photography was invented specifically for this picture to be taken at this time and place! Not really: It's sometime after 1815, but before now...but I totally had you going there for a second. The Fuerte de Loreto at the moment of its conception in 1815: Photography was invented specifically for this picture to be taken at this time and place! Not really: It's sometime after 1815, but before now...but I totally had you going there for a second. |

|

Is that because the shrine to Guadalupe was demolished when that fuerte was built, while Loreto's shrine remained intact in its fuerte? Does less demonstrative religious presence make a starfort fiercer? The 19th-century Spanish would beg to differ. The round bastions of the Fuerte de Loreto run counter to the accepted rules of starfortery even into the 19th century, but as a hilltop fort, its designers may not have expected troops and/or artillery to be unleashed upon it in such concentration as to make angled bastions necessary...or, maybe they just thought it just looked cooler with round bastions. Like a crusader fort! Romantic. Mexico finally won its independence from Spain in 1821, and all Spaniards were ejected from Puebla. Mexico was an independent nation, but it swiftly found trouble when Remontel, a French pastry chef with a business in Mexico City, had his shoppe ransacked by drunken Mexican soldiers. When news of this international outrage reached France in 1837, the French Navy was dispatched to Veracruz, where it pulverized the Fortaleza de San Juan de Ulúa. Veracruz was occupied by the French for over a year, until Great Britain finally intervened in a diplomatic fashion and the French returned home, confident that they'd made their point. This fracas is known today as the Pastry War. I'm serious. Though Mexico had a new respect for pastry, its troubles were far from over. The United States annexed Texas in 1845, which may have been the wish of the majority of the (white) folks living there, but Mexico still considered it to be Mexican territory. Armed clashes ensued, and the United States declared war on Mexico on May 13, 1846.

|

Siege of Puebla, an 1850 chromolithograph by James T. Shannon. Not terribly illustrative: Perhaps that's the Citadel of San José to the right, and the Fuerte de Loreto atop the far hill? Everybody certainly looks busy, in any case. Siege of Puebla, an 1850 chromolithograph by James T. Shannon. Not terribly illustrative: Perhaps that's the Citadel of San José to the right, and the Fuerte de Loreto atop the far hill? Everybody certainly looks busy, in any case. |

|

Veracruz was swiftly inundated with guys in blue uniforms, and General Winfield Scott (1786-1866) captured Puebla with no resistance: Scott, the future Old Fuss and Feathers, set up shop in the Fuerte de Loreto for the brief period he was in Puebla.

Mexico City fell soon thereafter, but while Scott's attention was thereupon directed, two Mexican forces, one of "irregulars" under the command of General Joaquín Rea (d. 1850) and the other under past-and-future Mexican President General Antonio López de Santa Anna (1794-1876), laid siege to the 400-man American force left to garrison the Fuerte de Loreto.

|

|

|

The Norteamericaños also occupied the nearby Citadel of San José, in which some 2,000 wounded and sick US soldiers were being cared for...under what were doubtless spectacularly clean, healthful conditions. The Mexicans numbered something over 4,000, but in a series of attacks they proved unable to dislodge the Americans. The standoff lasted for 28 days in September and October of 1847, until an American relief force defeated Santa Anna at the Battle of Huamantla, and made it to Puebla on October 12 where they lifted the siege. Saved! Winfield Scott was no stranger to starforts. During the War of 1812 (1812-1815) he led an heroic attack on Fort George, across from Fort Niagara on the Niagara River. This effort was a success for Scott, as the British fort was taken, though its garrison managed to escape capture.

|

|

|

...which may have made sense in the abstract, as those loans had been made to Mexico's conservative party, which had been violently ousted by Juárez and his minions over the previous several years, but just try explaining that to England, Spain and France. Add the facts that, a) the United States was occupied with fighting amongst itself in the form of the Civil War (1861-1865), and b) Napoleon III (1808-1873) was firmly convinced that he was the second coming of his uncle, Napoleon I (1769-1821), and wished to establish his own overseas empire...and what you've got is trouble a-brewin' down in old Mexico.

On December 8, 1861, the navies of France, the United Kingdom and Spain disgorged troops into Veracruz, intending to make everyone miserable until Mexico agreed to resume payments on its loans. Spain and the UK eventually realized that France's Mexican motives weren't as pure as their own, whereupon they made their own financial settlements with Mexico and departed. France, meanwhile, was there to stay.

|

The Ignacio Zaragoza Monument in Puebla, under which the man himself may or may not be entombed: There are a few monuments to Zaragoza in Puebla, and he's buried under at least one of them. The Ignacio Zaragoza Monument in Puebla, under which the man himself may or may not be entombed: There are a few monuments to Zaragoza in Puebla, and he's buried under at least one of them. |

|

France's impure intention (which was at least partially at the request of Mexico's conservatives, who had been trounced on the battlefield by the liberals) was to establish Maximilian von Habsburg (1832-1867), an Austrian archduke, as Emperor of Mexico. Thus ensconced, he would be expected to grant whatever wishes that Napoleon III might regally utter.

As had ever been the case, the way to Mexico City was through Puebla, and at the beginning of May, 1862, the 8,000-man French Expeditionary Force under Major General Charles de Lorencz headed west from Veracruz to dispatch this dumb little town with its two dumb little starforts...and then on they would effortlessly sweep to Mexico City. |

|

|

Unfortunately for the French, they were misinformed as to the level of displeasure Puebla's residents felt for the Mexican Republic: "My soldiers will be covered in flowers," reported de Lorencz to his superiors, having been assured that Puebla was an enemy of Mexico's government.

But if the Pueblans disliked the Mexican Republic, they apparently disliked the French even more. Mexican General Ignacio Zaragoza (1829-1862) placed troops at both of the town's fuertes and at various other strongpoints in and around the city...and they weren't armed with flowers. Unfamiliar with the terrain and too complacent to actually scout the location, de Lorencz launched three attacks straight up the hill towards the Fuerte de Guadalupe, supported by artillery.

|

While that artillery pretty much destroyed el fuerte, the French infantry, mostly consisting of nattily-uniformed Zouaves, were unable to get up the hill in any numbers. Zaragoza's scrappy, outnumbered and mostly untrained troops, firing from the fuerte's walls and trenches arrayed atop the hill, defeated what was, at the time, considered to be the finest of Europe's armies. Their artillery out of ammunition and harried by Mexican cavalry, the French limped back to Veracruz. Zaragoza's description of the battle was that the French troops behaved bravely in combat and their leader clumsily.

Jubilation! International amazement! Zaragoza, the hero of the hour, sadly succumbed to typhoid just a few months after the sacred battle date of April 5, 1862.

|

|

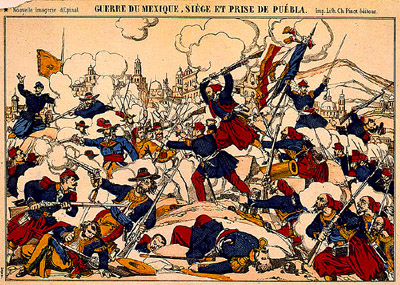

Guerre du Mexique, Siége et prise de Puébla, from a French magazine around 1870. This depicts the second battle for Puebla during the French Intervention, on which occasion the French did not lose. Guerre du Mexique, Siége et prise de Puébla, from a French magazine around 1870. This depicts the second battle for Puebla during the French Intervention, on which occasion the French did not lose. |

|

President Juárez changed the name of Puebla to Puebla y Zaragoza, and declared May 5 to be a national holiday into perpetuity, to honor the day that Mexico had been saved from foreign intervention!

...for about ten months anyway, because toward the end of 1862 Napoleon III dismissed de Lorencz, sent more troops to Veracruz, and impatiently pointed at Puebla. By the middle of March, 1863, the French were back at Puebla, this time surrounding the town and closing in. The battle brought with it fierce street-by-street, house-by-house fighting through the city, and both of our fuertes were heavily damaged in the melée: The Fuerte de Guadalupe, already a mess from the first battle in the previous year, was particularly pulverized.

For a brief, shining moment, it looked like the old Cinco de Mayo magic might strike again, when another General named Ignacio (which had been Zaragoza's first name) led a force of Mexicans that hoped to break the siege...on May 5, 1863. General Ignacio Comonfort (1812-1863)'s effort was foiled, however, as were subsequent Mexican efforts to support the beleaguered defenders of Puebla. The garrison finally threw in the towel on May 16, and marched away the following day. France occupied Puebla and what was left of its forts, and the road to Mexico City was open.

|

The Ignacio Zaragoza Monument in Puebla, under which the man himself may or may not be entombed: There are a few monuments to Zaragoza in Puebla, and he's buried under at least one of them. The Ignacio Zaragoza Monument in Puebla, under which the man himself may or may not be entombed: There are a few monuments to Zaragoza in Puebla, and he's buried under at least one of them. |

|

Maximilian ascended to the throne as Emperor of Mexico, but Juárez and his followers (known as "Mexicans") were never defeated. With the end of the US Civil War in 1865, America gave increasing aid and comfort to Mexico's Republican forces, and in 1866 French troops were withdrawn. Napoleon III delicately suggested that Maximilian might try to be an Emperor elsewhere, but the twelve Mexicans who still wished for him to remain in power convinced him to stay. The World's Least Successful Emperor was captured by Republican troops in 1867, and executed on June 19 of that year.

Both of Puebla's astrofuertes came out of this unfortunate period of Mexico's history as equally unfortunate ruins. |

|

|

In 1930, the hilltop above Puebla, with both of its heroic forts, was named "property in the service of the nation," recognizing its historic import: Today the whole area is known as the 5th of May Civic Center, and/or Zona Histórica de los Fuertes, for some reason. Restoration of the fuertes churned along for some decades, and in 1972 the Fuerte de Loreto opened as the Museum of Non-Intervention, highlighting the fact that Mexico, given the choice, would not choose to be intervened in any more, thank you very much.

Requiring further restoration was the Fuerte de Guadalupe, which was finally opened to the public in 2012, on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the famous battle in which the French were defeated. The Fuerte de Guadalupe is now a museum filled with artifacts from the heroic era in question, while the Fuerte de Loreto's displays are more devoted to telling the story of the battle itself.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|