|

Fort Ninety Six

Ninety Six, South Carolina, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1780

Used by: Great Britain

Also known as: Star Fort

Conflict in which it participated:

American Revolutionary War

|

Places named for numbers, such as Ninety Six, are generally named thus due to their distance from something important...which may have been the case with Fort Ninety Six, but the simple fact is that the little colonial town of Ninety Six wasn't ninety six units of established measurement from anything.

One theory is that traveling English traders estimated this tiny settlement was 96 miles from the Indian village of Keowee, to Ninety Six's northwest next to the modern city of Clemson...which is actually 81 miles distant. |

|

|

|

But, the landbound mariners of the 18th century had no Google with which to check their distances, so we forgive them, because Ninety Six is a great name for a starfort: Much better than Eighty One. Before it was a starfort, however, it was a tiny settlement, first established in the early 1700's. White traders, hunters and trappers from Charleston oozed into South Carolina's backwoods in the 1730's. The resident Indians, predominantly Cherokee, did not care for the settlement that followed, but settle the English folks did...because if we've learned anything in our study of the early United States, it's that white folks sure could settle.

Settlements-a-plenty there were in the backwoods of South Carolina, but Ninety Six developed into something special. While most backcountry settlements of this period were relatively lawless enclaves, the residents of Ninety Six built a proper courthouse and jail, whence colonial justice was lawfully dispensed. The village was conveniently located on the Charleston Road, which led to the city that you've probably already guessed, being the clever person that you are.

|

Naught but a rectangle shape on the ground remains of the original village of Ninety Six today: Because the bloody British burnt it down in 1781! Naught but a rectangle shape on the ground remains of the original village of Ninety Six today: Because the bloody British burnt it down in 1781! |

|

All of which brings us to 1759, when South Carolina's colonial Governor William Henry Lyttleton (1724-1808) directed that a 90-foot, square stockade fort be built on a plantation close to the village of Ninety Six. This temporary fortification, called Fort Middleton, was built due to the ongoing hostility of the Cherokee, who attacked the fort on two occasions...but as the Cherokee had yet to develop artillery, they were unable to penetrate the fort, temporarily stockadey though it may have been.

Governor Lyttleton played a major role in South Carolina in the years preceding the American Revolution: By conscientiously insisting that all treaties betwixt Indians and colonists be followed to the letter, he pissed off the colonists, which led to their disaffection with British rule. |

|

The American Revolutionary War made things weird for just about everybody in Britain's North American colonies. Shall I swing Patriot or Loyalist, wondered a great many colonists. Ninety Six opted for Patriot in the early years of the war. Another fortification, this time in the location of the present Fort Ninety Six, was built in 1775 to check the advance of the dastardly Loyalists. This was a larger edifice, 185 feet square, built with "a variety of materials," which one assumes means more than just wood: perhaps earth was used as well!

This fortification was named Fort Williamson, after the Patriot Major Andrew Williamson who saw to its construction. British Loyalists captured the town of Ninety Six in 1775, but were unable to crack the fort: After a brief siege, they threw up their Loyalist hands and moved on, leaving Ninety Six to its own Patriot devices.

|

But it was the Patriots who had moved on by 1780, when British Loyalists returned in force and began work on Fort Ninety Six's final iteration. This would be a military complex, including the eight-pointed starfort, a bastioned stockade completely surrounding the town of Ninety Six, and a separate Stockade Fort, which was intended to protect the spring that supplied Ninety Six with water...all of which were connected by a covered way, or communications trench.

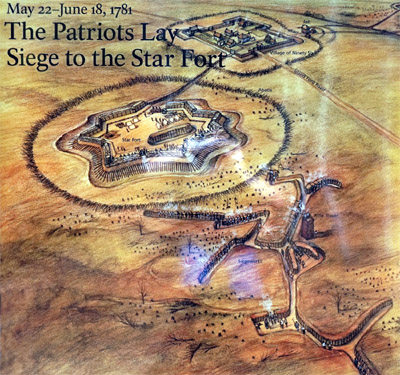

The British preparations were put to the test in May of 1781, when a 1,000-man Patriot force under the command of Nathanael Greene (1742-1786) arrived at Ninety Six, and immediately besieged the starfort of our current interest. Greene had been doing a pretty good job of eroding British control of South Carolina over the past several months, and his army outnumbered Ninety Six's defenders, which were 550 strong.

The fort's garrison was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John Cruger, and was armed with three, three-pound field pieces.

|

|

A sign from the site. One of the things that makes Fort Ninety Six so cool today is the remains of not only the fort itself, but the Patriot siegeworks that snaked their way towards the fort: The European art of approaching a besieged starfort by way of intense and very specific digging is not something one sees a lot of on this side of the ocean! A sign from the site. One of the things that makes Fort Ninety Six so cool today is the remains of not only the fort itself, but the Patriot siegeworks that snaked their way towards the fort: The European art of approaching a besieged starfort by way of intense and very specific digging is not something one sees a lot of on this side of the ocean! |

|

Which were little things, but depending on what one's opponent brings to bear, one's defending artillery may or may not be a deciding factor if one's starfort is built properly...and Fort Ninety Six, also eponymously known as Star Fort, was built properly. Its walls were 14 feet high, with a ditch all the way 'round. It had a powder magazine and a "traverse" inside, which was an extra raised area, which would serve as a redoubt in case those pesky Continentals got past the fort's walls...and there was a nice, pointy abatis around everything for good measure.

Greene's secret weapon, however, was Polish military engineer Tadeuz Kościuszko (1746-1817). Having learned in Paris the classic European art of siegecraft, Kościuszko immediately set to work, directing the digging of approach trenches that was, save surprise, the only proven method of engaging and defeating a determined enemy in a starfort.

|

Viewed from inside the fort, the mine, the tower and a field piece: Three means by which the Americans did their level best to take Fort Ninety Six. Viewed from inside the fort, the mine, the tower and a field piece: Three means by which the Americans did their level best to take Fort Ninety Six. |

|

But despite the earnest intentions of Kościuszko, Greene and the 1000 other gentlemen in blue coats and tricorne hats, Star Fort was...a starfort, a tough nut to crack under any circumstances. When a starfort's garrison stayed and defended themselves, as opposed to flailing their arms and surrendering at the first sight of an enemy (which was the historic undoing of many a starfort), they were usually unassailable.

In the night of June 13th Kościuszko directed the construction of a 30-foot-high wooden tower, about 30 yards from the southern walls of Star Fort. Though seemingly an unlikely, medieval gambit, this tactic had been used successfully a couple of months previously when such a tower was the deciding factor in the siege of Fort Watson, also in South Carolina. |

|

In that case, sharpshooters in their elevated, protected shooting position were able to pin down Fort Watson's Loyalist defenders long enough for the Continentals to storm the fort's walls. Fort Ninety Six's garrison, however, was a wilier bunch, and piled sandbags atop their walls so as to mitigate the rifle tower's advantage. The Loyalists also attempted to burn down the wooden tower with the application of heated shot...but without anything as efficient as a hot shot furnace to heat their shot, they were only able to serve up warm shot, which wasn't hot enough to set anything ablaze. Kościuszko also directed the digging of a mine, intended to burrow under Star Fort's northern extent, packed with powder and then blow the Loyalists into the sky with a pleasing kaboom. The British were not idle while the Patriots were digging holes and building things, and sallied forth from their fort to raid the American work parties on several occasions. Kościuszko received his only wound of the campaign during one of these raids: He was bayonetted in the buttocks, a wound of which any man can be proud. |

Meanwhile, just up the hill to the west of the town of Ninety Six, the Stockade Fort was dealing with its own patriotic menace. American officer "Light Horse Harry" Lee (1756-1818) and his merry band of guys on horses, fresh from having participated in the defeat of numerous British forts and outposts (he and his men were there when the Rifle Tower turned the trick at Fort Watson), repeatedly attacked the Stockade Fort. Along for the ride with Light Horse Harry were South Carolina Militia commanders General Andrew Pickens (1739-1817) (after whom the stellar Fort Pickens in Pensacola, Florida was later named) and General Francis Marion (1732-1795)(the Swamp Fox, whose name went on to grace the Castillo de San Marcos for over a century as Fort Marion, which is what the United States called that fort (incorrectly) until 1942, when its proper name was restored, all due respect to the Swamp Fox). And while we're dropping all these names, it seems only proper to point out that Light Horse Harry Lee was the father of Robert E. Lee (1807-1870) who, as a US Army engineer, worked his magic on such American starforts as Fort Pulaski, Fort Monroe and Fort Wool, and later went on to do that thing during which he wore gray. Light Horse Harry did manage to capture the Stockade Fort, on June 18, but the clock had run out on Greene's attempt to take Fort Ninety Six. |

|

Ninety Six's partially reconstructed Stockade Fort. Ninety Six's partially reconstructed Stockade Fort. |

|

While the aforementioned trio of starfort royalty were capturing the Stockade Fort, Greene sent a Forlorn Hope to assault Star Fort and, true to the concept of the forlorn hope, it was repulsed with heavy casualties. Scouts had reported that a British relief force of 2,000 men under Lord Rawdon (1754-1826) was on its way, and Greene's desperate assault of June 18th was the Patriots' final throw of the dice before they were forced to withdraw.

|

The towering walls of Fort Ninety Six today. The towering walls of Fort Ninety Six today. |

|

Greene blamed his defeat on the lack of industry with which South Carolina Militia Generals Francis Marion and Thomas Sumter (1734-1832) followed orders to support him. Mind-bogglingly, Thomas Sumter was also involved in this fracas, and I don't need to tell you which famous American fort was named for him, do I ( Fort Sumter)? Whomsoever may have been to blame for the failure of the Americans to take Fort Ninety Six, I wish to point out that just about everybody who took part in this campaign got a starfort named after them... except Greene. |

|

In his memoirs, Lee blamed Kościuszko for the debacle, accusing him of mismanaging his resources, such as they were...but by just about all other accounts, the Pole did a bang-up job as an engineer for the Continental Army. And his name is listed on a plaque in the main entrance of Fort Ticonderoga, which details the names of the historic fellows who passed though that portal: Click here to see that awesome spectacle. All told, Greene lost about 150 men during the siege, while the defenders lost under a hundred. Lord Rawdon's force, after linking up with Cruger's, set off after the retreating Americans, but it was hot and everyone was sweaty, so the pursuit didn't last long. It was shortly determined that the Ninety Six complex couldn't be defended (even though it just had been pretty comprehensively defended), so the British withdrew...after burning the town of Ninety Six to the ground. The Loyalists who survived the siege were shuttled about for a time, and then resettled at the conveniently-named Rawdon, Nova Scotia in Canada after the war.

|

Once the wicked scourge of the British had been more or less ejected from the colonies, the US government confiscated lands that had belonged to Loyalists. One such tract of land was just a smidge to the north of what had been the Stockade Fort, and the village of Ninety Six attempted to reestablish itself there in 1783. The town was renamed Cambridge in 1787, but as time moved on, railroads became the lifeline of rural America, and Cambridge, which was two miles from the nearest railroad depot, withered and died by 1850. The modern town of Ninety Six sprung up near that depot, which rail line connected the cities of Columbia and Greenville.

|

|

A pile of rocks in the modern town of Ninety Six, South Carolina. A pile of rocks in the modern town of Ninety Six, South Carolina. |

|

Old Ninety Six was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1973, and Ninety Six National Historic Site opened to the public in 1976. The remains one sees of the fort and the Patriots' siegeworks are mostly reproductions, based on archaeological discoveries. A pleasant 1.5-mile paved trail snakes through the woods, past the fort, through the original town of Ninety Six, and up the hill past the partially-reconstructed Stockade Fort.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|