|

Fort Nieulay

Calais, France

|

|

|

Constructed: 1525, 1677-1679

Used by: England, France, Spain

Conflicts in which it participated:

Eighty Years' War, Second World War

|

Calais has a history to warm a starfort lover's heart. Captured by the English in 1347 following the Battle of Crécy, it remained the "brightest jewel in the English Crown" until 1558 when the French took it back...and was then captured by Spain in 1596. What do you get when three of the world's leading starfort-building nations spend time in charge of a city? Starforts starforts starforts!

A peek at the map will reveal that Calais is just about as close as one can get to England while still being on the European continent. Those White Cliffs of Dover can be easily seen from Calais on a clear day. |

|

|

|

This fact was not lost on Julius Caesar (100-44BC), who gathered five Legions (around 25,000 men), a thousand boats and two thousand horses there ('twas then known as the Roman castrum of Caletum) in 55BC, prior to his invasion of Britain.

Though Calais was already a natural harbor, Baldwin IV ("The Bearded")(980-1035), Count of Flanders, oversaw the excavation and enlargement of the port in 977AD. The town was also first seriously fortified at this time, with a castle and thick walls being erected. Surrounded by marshy territory, the town and harbor were only approachable by land with extreme difficulty, which made it a delightfully defensible district. Calais was further fortified in 1224 by Philip I (1200-1235), Count of Boulogne. Such close proximity to England led to much seaborne trade passing through Calais, with tin, lead, cloth, and most importantly, wool heading to the ever-embattled island kingdom.

|

45 degrees of Fort Nieulay. I know everybody's tired of hearing me praise Google Earth, but for goodness' sake, what a resource. 45 degrees of Fort Nieulay. I know everybody's tired of hearing me praise Google Earth, but for goodness' sake, what a resource. |

|

One of the weird factors that led to Calais becoming an English possession were King Edward III (1312-1377)'s claim to the throne of France. Due to a series of bloodline issues reaching back to the Norman Conquest of the 11th century, Edward could sort of make such a legitimate claim, but it seemed to have more to do with his desire to muddy the waters and grab lands that clearly weren't England's to grab.

But grab he did. French King Charles IV ("The Fair" and/or "The Bald")(1294-1328) had the temerity to die without any male heirs in 1328. |

|

Charles' maternal nephew Edward made his claim to the throne, but the French went with an actual French person, Philip VI ("The Fortunate")(1293-1350), instead. Edward accepted this at the time, but when Mr. Fortunate started confiscating English lands in France (which we would today pretty readily recognize as French lands, but England and France had been somewhat dynastically intertwined since the aforementioned Norman Conquest), Edward reasserted his claim and the Hundred Years' War (1337-1453) was off and running.

|

Following Edward's surprisingly lopsided victory over the French at the Battle of Crécy on August 26, 1346, the victorious English army laid seige to Calais in 1347. Calais put up enough of an "obstinate defense" to piss Edward off (how dare you defend your city from me!!??), and once the English had possession of the city they expelled almost all of its French inhabitants: This was now an English city! Which was backed up by the Treaty of Brétigny, ratified in October of 1360: Calais, along with the Guernsey Islands and a huge chunk of southwestern France were granted to England in perpetuity, in exchange for Edward giving up his claim to the French throne, and please would you go back to England now. Phew! Glad that's been settled! (Whatever the veracity of Edward III's claim to the French throne, every succeeding English (/British) monarch made the same claim, until 1801 when France got sick of the whole thing and became a republic.) Calais became an integral part of England, with its own representation in Parliament, but much of France was not convinced. A massive English fortification effort was thus undertaken, its linchpin being a system of sluices on the Hames River, the closing of which would render the surrounding countryside even more impassable than it already was by flooding it. Close to these sluices was a bridge over the Hames, which represented the only way to approach Calais from the landward side. These sluices and this bridge were to be protected by a fort, and that fort was Fort Nieulay. Many other fortifications were also built to defend Calais: The most interesting of these is Fort Risban, which will be poked at below. |

|

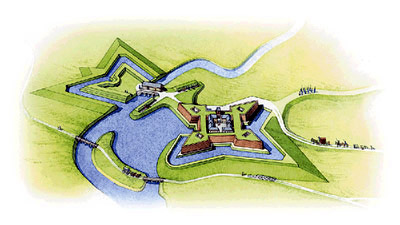

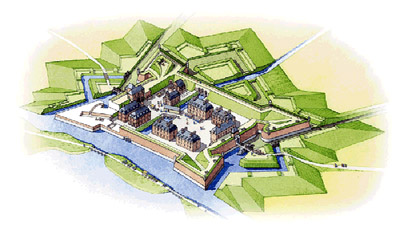

Three Ingeminations of

Fort Nieulay

Top to bottom: Fort Nieulay in its initial, castleoid English incarnation in 1525; The lovely Richelieuian starfort of 1637; and the Vaubannian masterpiece of 1677. I found these images on calais-avant-hier.eklablog.com's Fort Nieulay page, and while I suspect that they did not originally appear at that site, I would nonetheless like to thank them for these images, because I have to thank somebody for these images. Top to bottom: Fort Nieulay in its initial, castleoid English incarnation in 1525; The lovely Richelieuian starfort of 1637; and the Vaubannian masterpiece of 1677. I found these images on calais-avant-hier.eklablog.com's Fort Nieulay page, and while I suspect that they did not originally appear at that site, I would nonetheless like to thank them for these images, because I have to thank somebody for these images. |

|

The first little Fort Nieulay had a permanent garrison of 20 men, which would swell to 200 in times of need. As we can see in the illustration above, this was a wee darling pre-starfort, with four towers connected by curtain walls.

One of the reasons that Calais remained in English hands for so long was competition betwixt Burgundy and France, both of whom wished for Calais for themselves, and regarded its English possession to be preferable to those other French guys getting it.

Perpetuity only lasted for about 100 years in the case of most of England's French possessions: By the end of the Hundred Years' War in the mid-15th century, only Calais remained English. France finally got its collective act together in January of 1558, when King Henry II (1519-1599) sent a force under Francis, Duke of Guise (1519-1563) to retake Calais. This force managed to surprise the garrison at Fort Nieulay, the sluices remained open, and Calais was returned to the warm embrace of the French. Dancing in the streets of Paris, suicide in the streets of London.

|

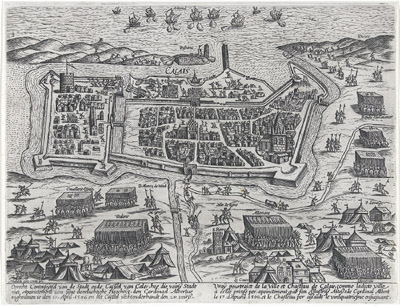

The Spanish siege of Calais in 1596. Note the Citadel attached, limpetlike, to the city to the left. That surrounding countryside sure looks solid enough to me! Fort Nieulay would be on the lower left of this picture, if this picture covered about twice the landmass that it does, which it does not. The Spanish siege of Calais in 1596. Note the Citadel attached, limpetlike, to the city to the left. That surrounding countryside sure looks solid enough to me! Fort Nieulay would be on the lower left of this picture, if this picture covered about twice the landmass that it does, which it does not. |

|

However. Y'know what was also going on relatively close to Calais? The unlikely entity that was the Spanish Netherlands. In 1558, thanks to a series of royal hop-skippity-jumpings, the states of the Holy Roman Empire in the Low Countries (today Belgium, Luxembourg, southern Netherlands, some of northern France and parts of Germany) were suddenly under the control of the Spanish Habsburgs: And King Philip II (1527-1598) was not the benign ruler that the dukes of Burgundy had been.

Now that Spain had troops stationed in the Spanish Netherlands, Philip had the means to conveniently throw his weight around in northern Europe. Some of his weight predictably fell on France, where in the early 1590's Henry IV (1553-1610) was attempting to secure the throne despite being a Protestant.

|

|

The mere thought of a Protestant king in Europe was of course ridiculous, as Philip and many other nearby crowned heads pointed out most vociferously. Henry eventually renounced Protestantism in order to become king of France in 1593, but by that point everyone in Europe had their own much more suitable candidate for French Kingship solidly in mind, and Henry finally declared war on Spain in 1595. In 1596 Calais found itself under siege by a Spanish army.

Once again the vaunted sluices at Fort Nieulay served no function whatsoever, and the city fell to the Spanish on April 24, 1596. The Spanish recognized Fort Nieulay's brilliant if unused sluice system for the strategic asset that it was, and improved the position by lowering the height of the English fort's four towers, and surrounding the whole thing with earthen bastions in the shape of a pleasing four-pointed star. Their tenure in Calais was brief, however, as the Treaty of Vervins (May 2, 1598) forced them to leave French territory.

|

In 1610, eight-year-old Louis XIII (1601-1643) ascended to the royal throne of France. Any eight-year-old is naturally going to need some serious oversight when ruling a major European nation, but it turned out that Louis was a bit of a weenie, and even upon some aging was unable to rule much of anything on his own.

As such, a variety of stronger-willed persons did the actual ruling of France during the Louis XIII administration, which is why we have Cardial Richelieu (1585-1642) to thank for Fort Nieulay Version 3.0. The Red Eminence is credited with our fort's 1637 upgrade, in which the Spanish fortification was solidified, and a really quite lovely hornwork was added on the eastern side of the bridge over the Hames River. The permanent garrison of this Fort Nieulay was 80 men.

|

|

A pretty drawing of Fort Nieulay in its 1630's incarnation, featuring the gorgeous hornwork across the river! Interestingly, the fort appears to be named "Nieulet" in this drawing? Which would of course be pronounced "Nieulay" to those of us who don't speak French, and those of us who pretend to speak French because it makes us seem refined. Could "Nieulay" be an anglicization of "Nieulet?" Why would it have been anglicized? A pretty drawing of Fort Nieulay in its 1630's incarnation, featuring the gorgeous hornwork across the river! Interestingly, the fort appears to be named "Nieulet" in this drawing? Which would of course be pronounced "Nieulay" to those of us who don't speak French, and those of us who pretend to speak French because it makes us seem refined. Could "Nieulay" be an anglicization of "Nieulet?" Why would it have been anglicized? |

|

You will note that the above right image of Richelieu's Fort Nieulay shows the fort's name as "Nieulet," which may have been a Frenchification of the English "Nieulay?" What I can't seem to discover is, did the English refer to their version of the fort as Nieulay? And when the Spanish held the fort, did they call it "Gnuleigh?" Seems unlikely.

|

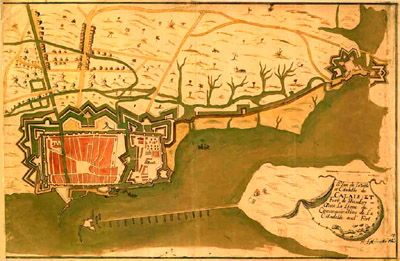

Calais in the 1630's, turned 180° for convenience. There's spunky lil' Fort Nieulay 3.0 up there at the top right! At least it's spelled correctly on this map. Calais in the 1630's, turned 180° for convenience. There's spunky lil' Fort Nieulay 3.0 up there at the top right! At least it's spelled correctly on this map. |

|

As important as the oft-mentioned sluices were at Fort Nieulay, they and the all-important bridge over the Hames were still outside the fort, which was immediately recognized by a sharp eyed-Vauban (1633-1707) when he came a-visitin' in 1675. Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban was of course the Father of the Starfort, whose innovative principles of fortification defined starfortery for the remainder of the time there was starfortery. He directed that Fort Nieulay should be razed, and a new fortification was built slightly to the east, this time surrounding the bridge and sluice gates. This was the final Fort Nieulay that we see today, because duh, nobody could build a better starfort than Vauban! |

|

Calais had withered on the vine by the end of the 18th century, with the nearby competing French ports of Dunkirk and Boulogne increasing in portitude. While loads of folks were being entertainingly beheaded all over the rest of France during the French Revolution (1789-1793), Calais missed out on this important cultural experience. Much as Julius Caesar had found Calais to be the place whence to undertake an invasion of Britannia, Napoleon (1769-1821) had similar designs, and a French army coalesced at Calais in 1805 in preparation to cross the Straits of Dover. The Royal Navy could not be persuaded to be elsewhere, however, and the invasion was never launched.

The swampy land surrounding Calais was "reclaimed" over the first half of the 19th century, and Fort Nieulay's sluices could finally be closed or opened just for kicks, with no resulting watery devastation. What fun whatever remaining garrison must have had playing with those sluices! While it certainly seems as though they could have been manipulated to good effect on more than one occasion in this history, the sluice option would have been a very last-ditch effort: Imagine the devastation to everything around the city if the area were flooded as intended! Such destruction may have been better than capture by a foreign power, but not by much.

|

The regions of France that were contested by others moved away from Calais, and Fort Nieulay fell into a predictable state of ruin. The fort was finally decommissioned in 1903, its interior rented to local farmers as a corral for livestock. Which, if you think about it, is an ideal repurposing for an enclosed starfort, as long as that livestock can be responsible enough to not fall down stairwells or be struck by crumbling masonry.

Fort Nieulay's final conflict was not to be betwixt squabbling piles of cow poop, but took place during the Second World War (1936-1945). As the Nazis were grinding the British Expeditionary Force towards its heroic retreat from Dunkirk in May of 1940, a scrappy force of 3,000 British and 800 French troops dug into Calais, which forced the Germans to divert the 10th Panzer Corps, artillery assets, and eventually a large contingent of the Luftwaffe to crush them. Opinions vary, but this desperate action likely helped 300,000 British troops to evacuate from Dunkirk.

|

|

Only France would have a dedicated "Falling Masonry from Deteriorating Starfort Bastion" road sign. Thanks to Moonsieur P for the inspired photography! Only France would have a dedicated "Falling Masonry from Deteriorating Starfort Bastion" road sign. Thanks to Moonsieur P for the inspired photography! |

|

Though Fort Nieulay was already in a much deteriorated state, a small number of French troops therein held out against the Germans for a couple of days, until a massed tank barrage finally convinced them that World War Two was no place for a starfort, and they surrendered. Calais was flattened by Panzers, artillery and precision Stuka bombing during this three-day battle, and only around 400 of the British/French defenders were "lifted" to safety by the Royal Navy.

Fort Nieulay in February of 2018: It's still there! Fort Nieulay in February of 2018: It's still there!

Germany made Calais their headquarters for the coastal defense of Fortress Europa and heavily fortified the city, expecting that any Allied landing effort would concentrate there. V1 "Buzzbombs" were launched from Calais into Britain, and massive railway guns were utilized there as well: An enormous concrete Railway Gun Shelter still squats menacingly just to the west of the city's Citadel.

|

Happily, Calais was liberated in October of 1944 by the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division....after which Britain's RAF bombed the city one last time in February of 1945, mistaking it for Dunkirk.

One of Calais' exports is...pebbles! These much sought-after pebbles made trouble for Fort Nieulay when locals scooped up scads of them from the starfort of our current interest's foundations following the war, causing the collapse of part of the southeast bastion. A restoration effort gained traction in the 1980's, however, and the spiffily pointy-looking Fort Nieulay is today open to the public.

Also guarding Calais...

|

|

The word sluice has now appeared on this page twelve times, so it seems only fair to show you what they look like. That's them under the bridge o'er the now non-extant Hames River, with the remains of Fort Nieulay's chapel next to it. Sluice: Lucky thirteen. Thanks for the image, Fortified-Places.com! The word sluice has now appeared on this page twelve times, so it seems only fair to show you what they look like. That's them under the bridge o'er the now non-extant Hames River, with the remains of Fort Nieulay's chapel next to it. Sluice: Lucky thirteen. Thanks for the image, Fortified-Places.com! |

|

|

|

Fort Risban began life as the wooden Lancaster Tower, which was built by the English during their 1346 siege of Calais at the mouth of the harbor, to prevent the besieged French from resupply by sea. French upgrades after Calais was theirs again transmogrified Lancaster Tower into the masonry Fort Risban, with which Vauban was unimpressed when he surveyed the city's defenses in 1675. The Father of the Starfort (and Author of the Pithy Quip) described Fort Risban as "a retreat of owls" and "a nice place to spend a Sunday afternoon," and suggested some improvements which, due to financial issues, were never acted upon.

What Vauban denigrated: Fort Risban vol. 2.0, circa 1604. What Vauban denigrated: Fort Risban vol. 2.0, circa 1604. |

|

As a security measure, ships that entered Calais Harbor were required to store their powder and shot in Fort Risban's magazine...which seemed like a great idea until the morning of June 11, 1799, when that magazine exploded. A Monsieur Louvet, keeper of the fort, was killed in the blast.

|

One of Vauban's suggested improvements had been the addition of a dedicated powder magazine, as opposed to just cramming munitions into the base of the demilune facing the city, which was precisely what blew up in 1799. Out of the question, laughed the Calaisians at the time.

Fort Risban was given its more or less present (weird) outer appearance in 1842.

|

|

|

|

In 1888 the remains of the ancient English tower were integrated into the powder magazine that Vauban had suggested two centuries previously. Fort Risban continued on as a storage depot for the many ships that came and went from Calais. Townsfolk and Allied soldiers sheltering in Fort Risban during the German siege of May, 1940 found themselves buried under Risbanian rubble after an artillery strike...most somehow survived this experience, and lived to enjoy the gentle ministrations of the Nazis.

Pounded badly in the war, in the 1950's our fortlet saw new life as the home of the Yacht Club of the North of France (and the pottery workshop of Madame Peumery, and I'm sure we've all heard of the Madame Peumery), whose loving attentions helped to reconstruct much of the fort. Further restoration has taken place recently, and the fort is today accessible to the public, once that public has shown sufficient admiration for Madame Peumery's pottery.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|