|

Fort Nelson

Hampshire, UK

|

|

|

Constructed: 1861 - 1871

Used by: Great Britain

Conflicts in which it participated:

None

|

After the armies of Great Britain and Prussia finally defeated Napoleon (1769-1821) for good at Waterloo in 1815, England settled in for a long period of relatively peaceful prosperity.

Its navy ruling the seas, its factories providing goods to the world, and its army mostly chasing various darker-skinned, technologically underdeveloped peoples around, England was the most dominant force on the globe through the first half of the 19th century. |

|

|

|

But with this dominance came a certain level of complacency. While Prussia and France were making long strides into the advanced worlds of artillery and steam-powered warships by the middle of the century, Great Britain floated blithely along with the weaponry that had made it a world power 40 years previously.

|

|

|

Which was fine and dandy when Great Britain had no serious rivals, but those on the Continent had not been idle. After a generation of pseudo-shamefaced self-contemplation, France was clawing its way back onto the world scene by the middle of the 19th century, led by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, better known as Napoleon III (1808-1873).

By the end of the 1850's, Great Britain was officially freaked out by the possibility of French invasion. Added to Britain's concerns about France's bellicosity was the Gloire. |

|

|

Which translates, appropriately, as "Glory." The Gloire was the world's first oceangoing, steam-powered ironclad warship, which France launched in 1859. Intended to take advantage of the newest developments in rifled artillery and influenced by ironclad floating batteries that Britain and France had thrown together and effectively used against Russian shore batteries in the recent Crimean War (1853-1856), the Gloire and its sister ships represented a real threat to Britain's "wooden walls."

|

Fortunately, looking out for England was Lord Palmerston (1784-1865). Prime Minister from 1859 to 1865, Palmerston championed the cause of security through what became a vastly expensive program of fortification.

"We have on the other side of the Channel a people, who say what they may, hate us as a nation...and would make any sacrifice to inflict a deep humiliation upon England," said Palmerston around 1860.

Portsmouth had been Britain's primary naval yard since the days of King Henry V (1386-1422). After the French sacked that city on four occasions between 1338 and 1380, Henry began fortifying Portsmouth in 1418.

|

|

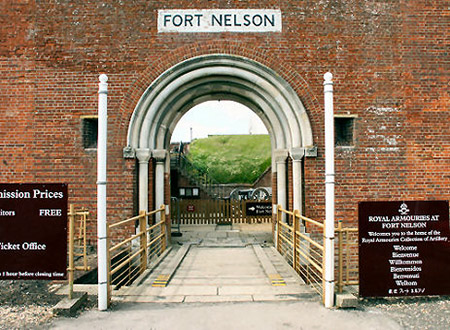

Lest there be any doubt, it's called Fort Nelson. Admission price: Free!! Lest there be any doubt, it's called Fort Nelson. Admission price: Free!! |

|

Directly across the English Channel lies Cherbourg. This had become a major military port for France during the Napoleonic Wars, and a huge fortification effort there had just been completed in 1850. As Cherbourg was just a lickety-split armored steam cruiser trip to Britain's most important military dockyards, Palmerston intended to fortify the ever-lovin' snot out of Portsmouth. Fort Cumberland, which protected the entrance of nearby Langstone Harbour, was completed in 1785. Fort Monckton, 1780. The last major fortification effort in Britain had been during the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), when a few hundred Martello Towers had been built along the coast, mostly to defend London from untoward French attention. Palmerston's plan, however, would eventually include over 40 individual forts, batteries and redoubts in support of Portsmouth alone.

|

The Nelson Monument, nearby on Portsdown Hill. The Nelson Monument, nearby on Portsdown Hill. |

|

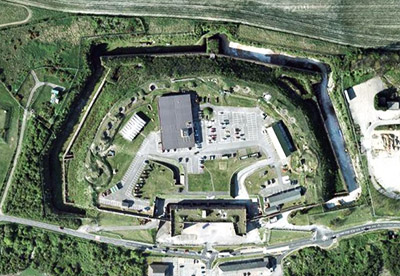

Fort Nelson, so named due to a nearby monument (erected in 1807) to Horatio Nelson (1758-1805), Godlike hero of the Battle of Trafalgar (1805), was one of five similar forts built along Portsdown Hill, the heights looking down on Portsmouth Harbour.

Why is Fort Nelson the only one of these five that I'm featuring here? Well. Only three of the others remain in place today, and you can see them below...but Fort Nelson is definitely the most starfortish one as far as I'm concerned. All five were really Artillery Forts, essentially just fortified, mutually supporting batteries for big guns. This was the fort concept that was sweeping Europe at the time, with such eastern European cities as Strasbourg and Kostrzyn being ringed with such forts. |

|

|

Which did these cities exactly no good whatsoever. Even by the time Artillery Forts were being expensively constructed, the concept of the defensive fort, utilized in this manner, was pretty much outmoded. Effectively manning and supplying all those forts was virtually impossible, and in just about every case these fortifications sat, mostly unused, until the First and Second World Wars rolled through with very little effort.

Fort Nelson's...caponniere? Southern pointy nub. Mind the gap. Fort Nelson's...caponniere? Southern pointy nub. Mind the gap.

|

In the summer of 1860, Royal Engineers waded through the standing wheat on Portsdown Hill, pacing off the spaces needed for forts. The government bought the land it needed from the Southwick Estate, and digging commenced a little later that year.

What's interesting to me about Fort Nelson is that, although it's certainly an Artillery Fort, its designers still wanted the wall-clearing defensive capabilities of a starfort, but obviously thought their friends would laugh at them if they built an actual starfort. As such, it has a series of doinky little caponnieres sticking out at each corner (including a ridiculous little bow at its northern tip), in which soldiers would be able to fire upon any Frenchie who made it to the fort's walls. It's still the basic concept of the starfort, without the big fat bastions, as the bastions didn't have to support cannon, just dudes with small arms.

Most of the Palmerston Forts around Portsmouth were complete by the end of the 1860's, but like governments everywhere, Britain's Parliament balked at the somehow unexpected cost of arming these forts after the massive expense of building them. Fort Nelson wouldn't be properly armed until the 1890's, but fortunately for England, Napoleon III undermined his own ambitions in 1870, by taking on Prussia.

|

|

|

|

Which was unwise. Partly manipulated into rash action by the brilliant machinations of Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck (1815-1898) and partly just because he was a twit, Napoleon III sent his army over the border into Prussia in August of 1870. Within a month, Napoleon III had been captured at Sedan, and Paris was under siege. Four months later, the war was over, the German states were united in victory, and Great Britain didn't have to worry about French armored ships any longer.

|

Today, the Royal Armouries Museum calls Fort Nelson home. Today, the Royal Armouries Museum calls Fort Nelson home. |

|

The Palmerston Forts around Portsmouth became popularly known as "Palmerston's Follies," as not only were they never apparently needed for anything, but their guns pointed inland, away from the harbour! Doesn't bloody Pam even know what direction to point the bleedin' guns!?

The forts were designed to deflect a landward attack, thus their guns were pointed inland. And it's quite possible that France did not attempt an invasion because of this massive fortification effort. But, y'know. Politics. |

|

|

Fort Nelson's first garrison, 178 troops of the 4th Regiment of Foot, marched into the fort on September 21, 1871, mere months after France had been decapitated by Prussia. Due to the rapid technological advance of artillery, the fort didn't receive its first guns until 1882: The original 68-pounder smoothbore guns intended for its armament were suddenly ridiculous. Further construction of concrete emplacements for rifled guns had to be completed, and by 1893 Fort Nelson was finally fully armed with 23 cannon (including 6.6-inch Howitzers and 7-inch Armstrong Guns) and two machine guns.

Most of which were removed and sent to the Continent for the First World War (1914-1918). By 1900 the forts on Portsdown Hill were declared obsolete. Fort Nelson housed some of Great Britain's early volunteers to fight in WWI. In 1939, at the start of the Second World War (1939-1945), Fort Nelson was again a busy hive of activity: It became the main storage facility supplying ammunition to Portsmouth's 58 anti-aircraft guns.

In 1995, the Royal Armouries Museum opened at Fort Nelson, with nearly 3000 pieces representing the history of British artillery. Included are captured French, Turkish, Indian and Chinese cannon.

Oh yeah, and there are three other remaining Palmerston Forts on Portdown Hill. All have remained in good condition, having been used by the Army or Navy for a variety of functions over the years:

|

Pronounced Suth-ik, Fort Southwick was the highest of the five forts on the hill, and held the water storage tanks for the others, delivering through a brick-lined aqueduct.

During the Second World War, this fort served as a communications center, and was an important communications hub for Operation Overlord, the Invasion of Normandy (June 6, 1944).

|

|

Directly to Fort Nelson's east: Fort Southwick Directly to Fort Nelson's east: Fort Southwick

|

|

|

"A Ghostly resident that many presume could be here is a Sergeant Major who enjoys whistling and haunting this fort." Thank you for this pertinent, factual information, Southwest London Paranormal Society.

|

|

To the east of Fort Southwick is Fort Widley To the east of Fort Southwick is Fort Widley

|

|

|

Fort Purbrook was completed in 1870. Today it houses a "Peter Ashley Activities Centre," with wall climbing, archery, shooting and horseback riding.

|

|

Furthest east in the line is Fort Purbrook Furthest east in the line is Fort Purbrook

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|