|

Castillo de Montjuïc

Barcelona, Spain

|

|

|

Constructed: 1694, 1779-1799

Used by: Spain, France

Conflicts in which it participated:

War of the Spanish Succession,

Napoleonic Wars

|

Montjuïc, Jewish Mountain, is so named due to the remains of a medieval Jewish cemetery found thereatop. This well-sited mountain, thoughtfully placed at the "foot of the Mediterranean" by fictional deity Hercules, had people living on and around it as early as 5000BC, and was the seed from whence sprouted the city of Barcelona.

Any town on the Mediterranean with an excellent harbor will attract Romans, and in 15BC Barcelona was developed into a Roman castrum, or fortified settlement. Montjuïc served as the quarry for the growing city: Its excellent sandstone was used for many of Barcelona's buildings. |

|

|

|

A signal tower, ispo farello, was built atop Montjuïc towards the end of the 11th century AD. A sailor on the mountain stood on his tippytoes and watched the sea for approaching ships, of whose arrival he would warn the town below with a system of sails during the day, and fires at night. Did this sailor ever sleep? Of course not, the safety of Barcelona hinged on his never-ceasing vigilance.

|

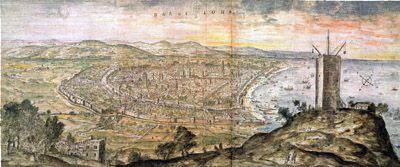

Barcelona in 1563, with the Ispo Farello atop Montjuïc in the foreground, by Antony van den Wyngaerde. |

|

Catalonia, the fiercely indpendant region of which Barcelona is the capitol, has been a semi-pseudo nation, occasionally, for a thousand years. Being situated betwixt two of Europe's most powerful and quarrelsome powers, France and Spain, afforded Catalonia plenty of opportunities to play the two off each other, but it has generally been associated with one of the two...usually Spain, and 'twas due to Catalan dissatisfaction with this situation that a fort was built atop Montjuïc.

|

|

|

The Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) was no picnic for anybody in Europe, and the Catalans found themselves forced to quarter Spanish troops-a-plenty, as well as being expected to bear more and more of the economic burden of Spanish King Philip IV (1605-1665)'s stupid war. With the curious battle cry of, Long live the faith of Christ, many Catalans rebelled against their Castillian overlords in May of 1640.

Barcelona's authorities built a defensive wall around the Ispo Farello atop Montjuïc shortly thereafter, which was then upgraded to what was probably an earthwork starfort...I'm guessing earthwork, because this small square fort with demibastions at each corner was built in 30 days! This fortification was manned by townspeople and some French troops (France had selflessly responded to a Catalan request for aid in this conflict, rewarding itself by snipping off some of Catalonia's northern territories for its own purposes), and mounted twelve artillery pieces.

|

However earthen this first fort atop Montjuïc may or may not have been, it was stout enough to deflect a Spanish attempt to seize it on January 26, 1641. Flushed with success, the Barcelonans further enhanced their fort in 1643, adding a drawbridge and ammunition-and-powder magazine...and, assumedly, building the walls back up with good Montjuïc sandstone.

For which the Spanish said muchas gracias in 1652, when the rebellion was finally crushed and Catalonia was once again under the control of the wicked Spaniard. A permanent Spanish garrison was billeted at the Castillo de Montjuïc so as to keep an eye on the potentially rebellious Catalans.

|

|

The Castillo, in all its 45-degree glory, from a postcard. The Castillo, in all its 45-degree glory, from a postcard. |

|

Further improvements were made to the Castillo during the Nine Years' War (1688-1697), which pitted France against just about everybody other than France. This war featured lots of naval activity on the Mediterranean, to which the Spanish at Barcelona were particularly vulnerable....but, sadly, nobody came to play with the starfort of our current interest.

|

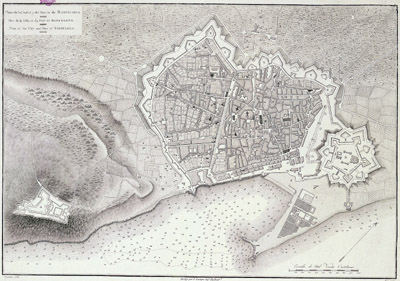

The fortified city of Barcelona in 1806. Imagine my surprise when I noticed that HUGE BEAUTIFUL STARFORT on the right! That was Barcelona's Ciutadella. Nothing remains there now, Barcelona has unsurprisingly expanded since 1806. In the spot where that monster starfort was, is now a lovely park with botanical gardens and a zoo. We will also note the Castillo de Montjuïc to the left, looking much as it does today. |

|

The War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) brought with it the complete destruction of the Castillo, from which ashes were born the sharply pointed marvel that we admire today. This war had to do with the question of whom should rule Spain upon the heirless demise of King Charles II (1661-1700), which the Habsburg Spanish thought was their decision to make, while the Bourbon Spanish were like nuh-uh, y'all. Most of the nations of Europe chose sides in this conflict, and the continent was off on yet another fun, devil-take-the-hindmost war-romp.

Catalonia entered the fray in 1705, on the Habsburg side. A French fleet and Bourbon army accosted Barcelona in April of 1706, and continued accosting it until the mighty Castillo had been pulverized by a lengthy bombardment.

|

|

|

When the war was finally over in 1714, the guy whom Charles II had appointed Spain's next king was still the king, and Catalonia had chosen its side unwisely. Barcelona had shown itself to be a less-than-fervent supporter of the Spanish crown, a slight which that crown did not intend to forget, nor allow to go unpunished.

Over the next few decades, a carefully-planned defensive system was devised for Barcelona, intended to both defend and contain the city. The city itself was surrounded with impressively starfortesque walls, the Castillo de Montjuïc was rebuilt stronger than ever, and an enormous new citadel, the Ciutadella, was built at the city's nor'eastern extent. The plan was for the new citadel to control Barcelona's defense from inside the city walls, while the Castillo de Montjuïc would be in charge of what was going on outside the city.

|

The devious mind behind this new operational concept was George Prosper Verboom (1665-1744), a Dutch military engineer working for Spain. Verboom (I cannot describe how pleased I am that someone named Verboom was responsible for building starforts) had worked some starfortin' magic at Antwerp early in the war, and his father, Cornelius Verboom, had had a hand in the fortifications at Besançon in France. Verboom the Younger masterminded the overall plan, but Barcelona's forts were designed by Juan Martín Cermeño (1700-1773), a Spanish engineer whose previous works included the fantastic Castillo de San Fernando, also in Catalonia... and some starfortage in Cuba. Work on the final version of the Castillo de Montjuïc commenced in 1753, and by 1799 the "irregular trapezoidal layout" of the fort was complete. The Castillo's odd shape came about due to the equally odd shape of the mountain atop which it was built. All of Barcelona's fantastic fortification improvements arrived just in time for the French to collectively lose their minds and set out on a world-conquering war spree. In 1792 France abolished its monarchy, and in January of 1793 it beheaded its ex-king, Louis XVI (1754-1793). This was met with a great deal of European disapproval (at least on the part of all the other monarchs), and an alliance was lashed together to put revolutionary France back in its monarch-led place. The War of the Pyrenees (1793-1795) was one of the first conflicts in what would become known as the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802).

|

|

One of the Castillo de Montjuïc's bastions. Which bastion is it? Hard to say for certain, but I would like to think it's the one at the fort's far southwestern extent. Whichever one it is, if you look carefully at the top of the garita, you'll see that it's been captured in a net! And thank goodness for that, that frisky garita has been driving me crazy dashing all over the place. One of the Castillo de Montjuïc's bastions. Which bastion is it? Hard to say for certain, but I would like to think it's the one at the fort's far southwestern extent. Whichever one it is, if you look carefully at the top of the garita, you'll see that it's been captured in a net! And thank goodness for that, that frisky garita has been driving me crazy dashing all over the place. |

|

The War of the Pyrenees took place, as one might imagine, along the Pyrenees mountain range that separates France and Spain. It involved lots of back-and-forth at such starforts as Bellegarde and Perpignan, and while the fighting didn't make its way to Barcelona, the Castillo de Montjuïc was used to hold French POWs. Despite the ongoing conflict, in 1794 French astronomer Pierre Méchain (1744-1804) utilized the Castillo to invent the Metric System! Okay not really, but he did make an exacting measurement from the Castillo de Montjuïc to a particular belfry in Dunkirk, England (deemed to be precisely half the distance from the equator to the north pole), from which he was able to produce the Prototype Meter Bar. This platinum bar was to serve as the basis from which all measurement would henceforth be conducted, and was placed in the National Archives, France's repository for important stuff. Méchain's magic platinum bar remained smug in its status as THE meter for 90 years, at which time the real meter was defined by the General Conference of Weights and Measures, which produced a platinum and iridium meter bar, which was given, for some reason, to the United States...which accepted this gift most gravely, and then proceeded to not really ever adopt the metric system.

|

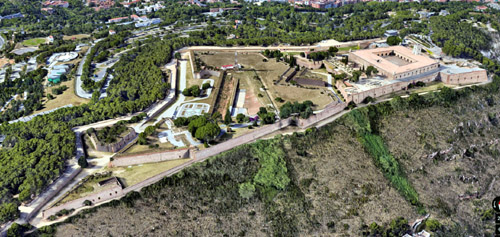

A breathtakingly lovely 45° screenshot of the Castillo from Google Earth. Thank you, Google Earth. |

|

Napoleon (1769-1821), meanwhile, had been busily conquering just about everyone arrayed against him. Napoleon's brother Joseph Bonaparte (1768-1844) was installed as the king of Spain, the French occupied Barcelona in 1808, and they took up residence in the Castillo de Montjuïc. Catalonia didn't fare well through the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), but the Castillo was well cared-for by its new owners.

|

|

|

Even after Napoleon was finally defeated and bundled off to the island of Saint Helena where he was unable to cause any more trouble, Catalonia was not a happy place. The Spanish took up residence in Barcelona's forts and kept a stern eye on the understandably semi-rebellious Catalans, whose political movements included everything from straight-up Catalan nationalism to anarchism (anarchy sounds great to the very young or the very poor, for whom things aren't going particularly well, but imagine how well one's plumbing and Internet would work under such a system!). Between 1842 and 1856, the Spanish garrison in the Castillo de Montjuïc and the Ciutadella bombarded Barcelona on four occasions, killing around 800 people and forcing repeated evacuations of the city. These judicious applications of justice caused the wayward Barcelonans to see the error of their ways, and the Spanish authorities were thereafter embraced with love and respect.

|

Well perhaps not, but the Barcelonan insurgents did make their own contributions to this bloody business. In 1896 an Anarchist attack on the annual Corpus Christi procession killed twelve people, which gave the Spanish authorities an excellent excuse to round up 700 Barcelonans it didn't like and drag most of them to the Castillo de Montjuïc (which by this time was being used as prison), where they were imprisoned, tortured and in some cases executed, by firing squad in the fort's moat. The Process of Montjuïc, as these events became known, gained international notoriety and universal censure. The Spanish bowed to public pressure and released the surviving prisoners of this fracas in 1901.

|

|

Not one of the guns used to mercilessly pound Barcelona. This is a Second World War-era gun, which would have been used to mercilessly pound anyone who contested Spain's neutrality in that war in a naval fashion. Not one of the guns used to mercilessly pound Barcelona. This is a Second World War-era gun, which would have been used to mercilessly pound anyone who contested Spain's neutrality in that war in a naval fashion. |

|

Further unpleasantness occurred in 1909, when the Spanish attempted to draft numerous Barcelonans into the army for its ongoing colonial war in Morocco. Massive unrest led to a general revolt, with a hundred folks being killed and around two thousand arrested: Five more detainees were shot in the Castillo de Montjuïc's moat. And again in 1919, three thousand who had refused their army call-up were imprisoned in the Castillo (how did that many people fit in our Castillo?!).

|

A handy map of the Castillo (Castell?). #11, the Santa Elena Moat, was the favored spot for firing squad action in the 19th and 20th centuries. Click it, it gets bigger. |

|

In April of 1931, Spanish King Alfonso XIII ("The African")(?!)(1886-1941), noting the widespread discontent in his kingdom, nobly initiated municipal elections throughout Spain, whose results, two days later, forced him to abdicate and flee the country. Barcelona's new city council immediately demanded that the Castello de Montjuïc, which represented the previous regime (and several regimes previous to the previous regime)'s murderous excesses, be abandoned by the central government. Plans to make the starfort either an anti-war museum or the seat of the new Parliament of Barcelona were bandied about, but there would be plenty more folks who needed incarceratin' in what was perhaps the least pleasant event amongst numerous other unpleasant events in Spain's history: The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939).

Our Castillo was seized by the "Committee of Antifascist Militias" in August of 1936, which body raised the Catalan flag therein, and hung a sign at the fort's main gate that stated, Order, Serenity and Discipline. No offense, Catalonia, but you could really use some help with your militant slogans. |

|

|

The Castillo de Montjuïc did what it has historically done best through history: Around 1500 people were imprisoned therein during the war, with 250 being executed in the time-honored fashion in the Santa Elena Moat. Unfortunately, Barcelona had again chosen unwisely in its affiliations, and the city was captured by the forces of Generalìsimo His Most Virile Excellency Francisco Franco (1892-1975) in January of 1939. Many of Catalonia's institutions were soon abolished, and even public speech in the Catalan language was suppressed.

|

Fantastic Fascist Franco was only too happy to utilize Barcelona's Castillo to his own ends, which were, you guessed it, the incarceration, torture and execution of lots of political opponents. Most famously, the 123rd president of Catalonia, Lluís Companys (1882-1940), was executed in the good ole Santa Elena Moat on October 15, 1940. Companys is the only incumbent, democratically elected president in European history to have been executed. Makin' history: That's Franco.

Franco himself visited Barcelona in 1960, at which time he "partially ceded" the Castillo de Montjuïc to the city, provided it undergo renovations and reopen as a military museum, for which the city was expected to foot the bill. In addition to various structural improvements, electricity and running water were added to the fort for the first time (1960), and the military museum was officially opened in June of 1963.

|

|

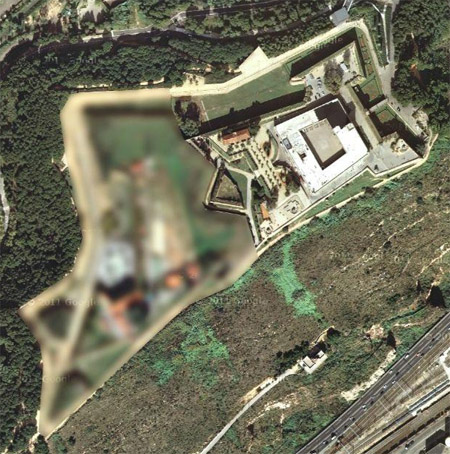

When I first investigated the Castillo in 2012, its southwestern extensions were selectively blurred on Google Maps. I assume that such strategic blurring is done at governmental request, but what was in need of obfuscation, and from whom were we hiding it? When I first investigated the Castillo in 2012, its southwestern extensions were selectively blurred on Google Maps. I assume that such strategic blurring is done at governmental request, but what was in need of obfuscation, and from whom were we hiding it? |

|

Fortunately for everybody, Franco did not live forever. He died in 1975, and in 1977 massive peaceful protests were held in Barcelona, demanding the return of Catalan autonomy, which was granted later that year. The Castillo remained in some semigovernmental state until 2007, when it was finally handed over to the Mayor of Barcelona. The military museum was dismantled, and in 2011 the same Catalan flag that had been raised o'er the fort by President Companys in 1936 was raised once again. It appears that some sort of "Peace Center" will be housed within the Castillo's walls.

Muchas gracias to Raquel Suma, who pointedly reminded us of the existence of the Castillo de Montjuïc.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|