|

Fort Massac

Metropolis, Illinois, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1757-1759, 1794, 1802,

1812, 1850

Used by: France, USA

Conflict in which it participated:

French and Indian War,

Northwest Indian War

|

The more astute observers among us will have noted that there are two starforts at the top of this page. As tempting as it is to imagine that this represents a constellation of starforts, cleverly built for river defense, what we're seeing is the original Fort Massac to the lower left, and a replica of Fort Massac as it appeared in 1802. To the best of my knowledge, this replica-next-to-the-original scheme is unique in the world of starforts.

Say what one will about the French, they sure built a lot of starforts. Imperial France built several forts in the Illinois territory from the late 17th century, when they first started exploring there, up into the 1750's, when they were fighting Great Britain for supremacy of the New World, in the French and Indian War (1756-1763).

|

|

|

|

What might have been the first fortification on this spot, however, was Spanish. Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto (1496-1542) may have built some sort of fort at this site as early as 1540, but details on this possibility are sketchy at best. Early 17th century French maps of the region do show an "ancien fort" at this location.

We are on more solid historical footing when we say that, 'twas in 1757 that the French, in the interest of securing their supply lines up the Ohio River, chose this spot to do their starfort thing. Just a mile or so northwest of the place where the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers meet made it a prime starfort location: French supplies and traders sailing up the Mississippi from New Orleans could take a right at the Ohio River, and would have a waypoint and/or place to hide along their route. This initial fort was named Fort Ascension, which translates to "Fort Ascent," which is likely due to the fort's location on a rise, 50 feet above the level of the river, affording a view of about three miles up and down the river.

|

The replica Fort Massac. Blockhouses anchor three of its four corners. The fourth corner? Aah, we just don't keep anything important in zat part of ze fort. Let ze English pigdogs have what zey will, n'est-ce pas? The replica Fort Massac. Blockhouses anchor three of its four corners. The fourth corner? Aah, we just don't keep anything important in zat part of ze fort. Let ze English pigdogs have what zey will, n'est-ce pas? |

|

Fort Ascension must have been a ramshackle affair, as it fell apart and had to be rebuilt from 1759 to 1760. The French renamed their fort Fort Massiac, in honor of Claude Louis d'Espinchal, marquis de Massiac (1686-1770), the French Naval Minister at the time. There is a commune of Massiac in southern France, of which this dude was the marquis, a minor nobleman.

The French and Indian War did not end well for the French or the Indians. France lost about a billion square miles of territory in the New World, and the Indians got what they always got, which was stepped on by everybody else. The French departed from Fort Massiac at the end of the war, and whatever was left of it was destroyed by Indians. |

|

|

Great Britain intended to occupy whatever pile of kindling was left of Fort Massiac, but it had a lot of new land to explore and occupy, and British troops never made it to the location of our current interest. This oversight was probably much lamented after American Brigadier General George Rogers Clark (1752-1818) crossed the Ohio River with 175 men at this spot June 28, 1778: This was during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). Clark and his men went on to capture a number of villages and forts in British territory with very little in the way of resistance, thanks to their speedy and stealthy approaches. Had the British flag been a-flyin' o'er a reconstituted Fort Massiac, Clark and his band of troublemakers likely would have been unable to perform these martial feats.

|

The Treaty of Paris (1783) spelled out the terms of Great Britain's defeat in the American Revolutionary War. One of these terms was that Great Britain cede control of the Northwest Territory, roughly the land east of the Mississippi River and south of the Great Lakes, to the new United States. Britain in fact pseudo-sneakily remained in place at a number of forts throughout the region for the next decade.

The Northwest Territory was of course occupied by a number of Indian tribes, which had no interest in being "controlled" by anyone, and who were supported and supplied to varying degrees by the British. Were the Indians being surreptitiously controlled by the British? Of course not. The British are gentlemen.

|

|

Pointy sticks always make for an heroic starfort corner. Pointy sticks always make for an heroic starfort corner. |

|

In 1785 US President George Washington (1732-1799) initiated an effort against the Indians in that territory, which became the Northwest Indian War (1785-1795). After a number of painful defeats, Washington appointed Revolutionary War hero "Mad Anthony" Wayne (1745-1796) to take command of US forces in 1794...and to get a starfort built at the site of the old French Fort Massiac immediately! At that time, this location was on the United States' western frontier. "Mad Anthony" would later have his own starfort named after him: Fort Wayne at Detroit, Michigan. Unfortunately, there is no Fort Mad Anthony. Frownyface.

|

The interior of the replica Fort Massac, beneath a suspiciously pink sky. |

|

US troops under the command of Captain Thomas Doyle arrived at the banks of the Ohio on June 12, 1794, and by October 20 had erected their starfort. Four months is an impressively brief period in which to complete a starfort, but we're not talking masonry and casemates here: It's wood.

The British have a long history of renaming things whose original name they can't pronounce, and Americans proved to be no less inclined to do so: Upon completion, the new fort's name was anglicanized to Massac.

By 1797, settlers were making their way west along the Ohio River into Illinois territory in large numbers, and Fort Massac served as an entry point into the region.

|

|

|

Tensions betwixt the US and France were mounting at the end of the 18th century for a variety of reasons, such as the United States' cozying up slightly with Great Britain (currently at war with France) thanks to the Jay Treaty of 1794, and the US' refusal to continue payment on its debt to France, seeing as the loans had been made by the French monarchy, which had been dumped by Revolutionary France, King Louis XVI (1754-1793) having been executed in 1793.

Illinois Territory was considered to be at risk if the French decided to get serious about prosecuting what would become known as the Quasi-War (1798-1800), and plans were made to garrison little Fort Massac with a thousand troops. This would have made for quite a crampy situation for everybody, but surely would have been plenty to handle anything a massively overextended French army could manage to get all the way up there, assumedly having sallied forth up the Mississippi from New Orleans. As it happened, Fort Wilkinson, a newer army camp a bit to the west at the tiny town of Grand Chain, was built up instead...and all for naught, as the few armed clashes of the Quasi-War occurred in the Atlantic, betwixt French and American warships.

|

Fort Massac was again rebuilt in 1802 and strongly garrisoned. Though things between France and the US had calmed down, the land to the west of the Mississippi was still under the nominal control of a foreign power: Spain. And then secretly France, when Napoleon (1769-1821) secured the territory from Spain in 1800, and then France sold all 828,000 square miles of the Louisiana Territory to the United States in 1803.

One of the first official movements of US troops into the Louisiana Territory took place in early 1804, when a detachment from Fort Massac crossed the Mississippi and occupied the town of New Madrid, in present-day Missouri.

|

|

Sunrise, or maybe sunset, at Fort Massac. Sunrise, or maybe sunset, at Fort Massac. |

|

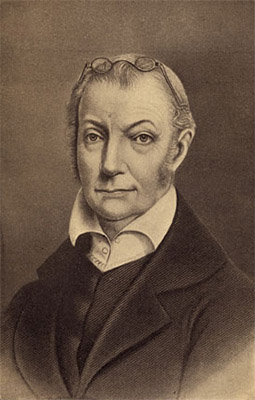

James Wilkinson: Agent 13 of the Spanish Crown. James Wilkinson: Agent 13 of the Spanish Crown. |

|

Shortly after purchasing the Louisiana Territory, US President Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) dispatched the Corps of Discovery Expedition, a group of volunteer US soldiers led by Captain Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809) and Lieutenant William Clark (1770-1838), to explore the western reaches of the continent. What is known to all American schoolchildren as the Louis and Clark Expedition began its journey at the city of St. Louis, but on their way they stopped at Fort Massac, where they recruited two more volunteers from the fort's garrison, for their mission of discovery (and hunger).

James Wilkinson (1757-1825), the interesting fellow after whom Fort Wilkinson had been named, was the first Governor of the Louisiana Territory after its purchase by the United States. He was so interesting because he was a paid informant to the Spanish Crown, who passed information to Spain in order to advance his business dealings. Wilkinson even informed the Spanish of the intention of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, which could well have caused that expedition's capture and execution, had Spain had a mind to do so, which they fortunately did not. |

|

|

It may shock some to also learn that American politicians have not always been the upstanding paragons of unimpeachable virtue that they are today. Consider, if you will, Aaron Burr (1756-1836). Burr was Thomas Jefferson's Vice President from 1801 to 1805, and is mostly remembered today for having taken the life of founding father Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804) in a duel in 1804. Which is despicable enough (even though it takes two to duel... dual?), but Burr also hatched a dastardly plan to create a huge, independent nation in the center of the North American continent, of which he would be the ruler. Did he intend to simultaneously serve as Vice President of the United States while ruling Burratopia or whatever this new nation would be called? Unclear.

In 1805, Burr met with Wilkinson at Fort Massac, where they rubbed their hands together and cackled in a conspiratorial fashion. Actually, it is believed that Burr attempted to recruit Wilkinson in the scheme to create a nation west of the Allegheny Mountains, but even the interesting Wilkinson recognized the ridiculousness of such an endeavor. Wilkinson would eventually write letters to Jefferson which sold Burr out, while of course painting himself in a flattering light.

|

|

Aaron Burr, early 1800's. Creepy. Aaron Burr, early 1800's. Creepy. |

|

To this point in American history, the position of Vice President had been filled by the gentleman who had lost the presidential election: The thought being, this person would put his petty jealousies aside and make his best efforts in support of the elected president, for the good of the nation. The experience with Aaron Burr who, once the full measure of his weird treason was revealed fled to Great Britain in 1808, made it clear that it was silly to expect the defeated presidential candidate to work well with the elected one.

|

This statue of George Rogers Clark sits at the site of the original Fort Massac. This statue of George Rogers Clark sits at the site of the original Fort Massac. |

|

Fort Massac, meanwhile, received another facelift in 1812, just in case it was needed for the upcoming War of 1812 (1812-1815), but it was not. Following that conflict the fort had a much lesser strategic importance as America's western frontier had moved several thousand miles west, and was finally abandoned by the US Army in 1817.

Only to be rebuilt, yet again, in 1850! Fort Massac was transmogrified into a factory fort! Designed to produce military supplies of many sorts, the fort was manned through the US Civil War (1861-1865), but was thereafter abandoned for good.

Fort Massac State Park was dedicated in 1908. |

|

|

A replica of the 1757, French version of Fort Massac was built in the early 1970's, next to the fort's original location. This was torn down in 2002, and a replica of the 1802 Fort Massac was constructed in its place. Hopefully this means we have a replica 1850 "factory fort" to look forward to in another 40 years?

Thanks once again to starfort enthusiast Ben, for finding Fort Massac for us!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|