One of the reasons that starforts spread so rapidly and successfully around the world in the 17th and 18th centuries was that the native peoples who populated those places which were not Europe couldn't (or in any case didn't) build starforts of their own. Many indiginous peoples utilized some form of fortification through history, but none that could successfully defend against Europeans with modern weaponry.

An exception to this rule, however, were the Maori people of New Zealand. The Maori's classical form of warfare involved warriors running through groups of their enemies at top speed, wielding razor coral-bladed clubs or spears, hacking once per victim before veering off to the next. Subsequent running warriors would deliver further individual blows. A single warrior could thus injure up to ten enemies, before either being taken out or becoming too exhausted to continue hacking.

To counter this hit 'n' run method of warfare, the Maoris developed the pā: Labrynthine hilltop fortresses, surrounded by a complex array of ditches, palisades and wooden walls. |

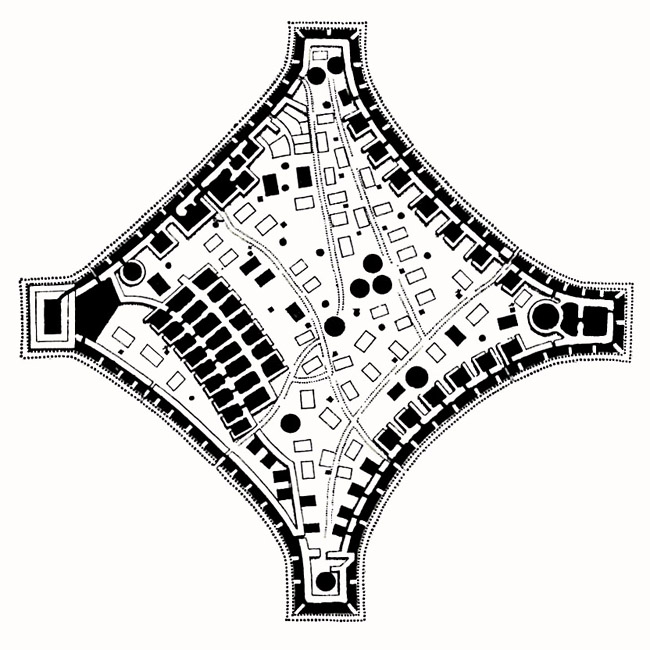

|

Tauranga Ika Pā, the finest (and possibly only) illustrated example of a Gunfighter Pā: Drawn from an 1869 survey by J. Buchanan, from James Cowan's book, The New Zealand Wars, Vol. II, 1922. Tauranga Ika Pā, the finest (and possibly only) illustrated example of a Gunfighter Pā: Drawn from an 1869 survey by J. Buchanan, from James Cowan's book, The New Zealand Wars, Vol. II, 1922. |

|

The pā is thought to have been a fairly standard part of many Maori villages by 1642, when the first Dutch explorers (on a ship captained by Abel Tasman (1603-1653) of the Dutch East India Company) showed up at what he named Staten Landt, to honor the Dutch parliament, known as the States General. No Europeans became acquainted with the pā on this voyage, however, as the Maoris violently and wisely chased off Tasman's landing parties. Dutch cartographers named the island after the province of Zeeland, which was later anglicised to New Zealand.

|

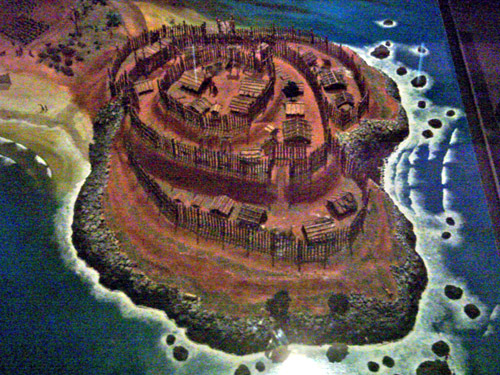

A model of a "typical pā," as in the non-gunfighter type, at New Zealand's Auckland War Memorial Museum. A model of a "typical pā," as in the non-gunfighter type, at New Zealand's Auckland War Memorial Museum. |

|

The pā developed by Maori to defend against other Maori took the form of the fort on the left: Terraces, earthen ramparts, ditches and palisades (stake fences) or wicker barriers, with plenty of underground storage. These storage areas included drainage systems to keep everything if not dry, then at least unsubmerged.

Meant to be a sanctuary in time of trouble, most pā were merely a place for the inhabitants of a village to huddle while under attack. Larger pā would sometimes incorporate the whole village they were built to defend, and though crops were chiefly raised outside of the fortified area, some had room for crops and livestock inside their walls.

Exact records were of course not kept during this period, but archaeolocal evidence shows that there were over 5000 pā in New Zealand. Compare this number to how many hill forts were thought to have existed in Britain (which is around 2000), and one gets an idea of how widespread was the pā! |

|

Maori culture was changed by the European introduction of the potato and the musket. The easy-to-grow and relatively nourishing potato enabled a surplus of food, which historically makes folks more willing to expand their boundaries, since everybody isn't constantly needed to produce or find food any longer; and the musket, for the unprecedented military advantage it gave to those tribes that yielded this cumbersome but deadly weapon. New Zealand's "Musket Wars" betwixt Maori tribes lasted from 1801 to 1840, killing 30,000 to 40,000 Maori.

All of this fighting, pā and musket experience on the part of the Maori gave the British a rude shock when they began pushing their weight around in a military fashion in the 1840's. The British experience in New Zealand followed the standard colonial pattern of contact, trade and eventually exploitation, when English settlers bought up scads of land from greedy Maori chiefs who were happy to sell lands that weren't theirs to sell, leading to predictable and passionate property disagreements.

|

So what turned an effective yet relatively unimpressive hill fortress into a starfort? The need to defend against adversaries armed with muskets and/or artillery, of course! Understanding the utility and limitations of the musket, the Maori enhanced the classic pā by giving it mutually supporting bastions, which any starfort fan will recognize as the hallmark of the starfort!

In the gunfighter pā, walls were made of stout tree trunks sunk four feet into the ground, protected by bundles of flax padding: This was enough to stop incoming musket rounds. Firing trenches allowed Maori musketeers to fire from under these walls, and there were often parapets on the walls to allow the defenders to simultaneously fire from above as well.

To me, the most exciting aspect of the gunfighter pā is its starfortesque shape, but the intricate trench and bunker systems therein elicited much more wonder, consternation and admiration on the part of the British. The Maori have even been credited with the invention of trench warfare, though most historians pooh-pooh this notion and point to the Crimean War (1853-1856) and American Civil War (1861-1865) as the birthplaces of that most advanced and humane of warfighting systems. |

|

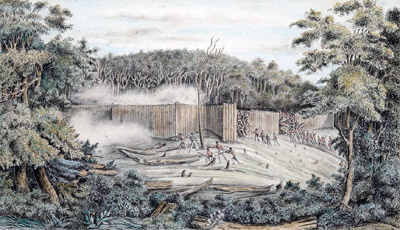

A gunfighter pā circa 1845, painted by a British officer by the name of Cyprian Bridge. Potatoes are being grown outside the fort...and it appears that the Maori solved the problem of needing constant watchmen, by sticking carved totems on each of the fort's corners, where a guerite might be on a starfort! A gunfighter pā circa 1845, painted by a British officer by the name of Cyprian Bridge. Potatoes are being grown outside the fort...and it appears that the Maori solved the problem of needing constant watchmen, by sticking carved totems on each of the fort's corners, where a guerite might be on a starfort! |

|

The counter to the gunfighter pā was of course an artillery-armed siege. The British certainly had the big guns at their disposal in New Zealand, but getting those guns to where they were needed in a trackless wilderness was a notoriously difficult enterprise...plus, the general opinion of British officers and the folks in London was that they were facing "a horde of half-naked, half-armed savages," so why should artillery even be necessary in their opponents' dispatch?

|

Some of Gate Pā's fiendishly clever trench system in 1864, drawn by a British officer after the Maoris (minus the guy lying facedown in the trench) had slipped away in the night. The paucity of local lumber is the reason for the scraggly-looking "wall" surrounding this pā, but the series of redoubts and cunning doggedness of its defenders more than made up for this lack. From The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Autumn 1994, Vol. 7, No. 1. Some of Gate Pā's fiendishly clever trench system in 1864, drawn by a British officer after the Maoris (minus the guy lying facedown in the trench) had slipped away in the night. The paucity of local lumber is the reason for the scraggly-looking "wall" surrounding this pā, but the series of redoubts and cunning doggedness of its defenders more than made up for this lack. From The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Autumn 1994, Vol. 7, No. 1. |

|

Why indeed. British troops soon learned a healthy respect for the gunfighter pā. Assaults thereupon were routinely repelled with heavy casualties to the attacking force, though in most cases the Maoris silently abandoned their lovely forts in the night when they sensed that their defensive advantage was lost.

Even when the British did effectively employ their artillery, as in the battle of Gate Pā in April of 1864, the complex trench systems within the fort made for deadly surprises. After eight hours of bombardment with guns and mortars, 300 British troops advanced on the apparently abandoned Gate Pā only to be fired upon at point-blank range by defenders in a camouflaged secondary redoubt. This sneaky yet effective ploy killed 31 British soldiers, wounded another 80, and sent the rest scampering from the pā.

The vastly outnumbered Maori slipped out of Gate Pā the following night, having suffered 25 casualties from the bombardment (bombproof bunkers had preserved most of them) and ill-fated British attack. |

|

As the Maoris lacked any sort of central engineering authority, there was no such thing as a "standard" gunfighter pā. While the undoubted advantage of the bastioned trace was easy for the Maori to recognize, different situations called for different designs of fortification. Kingites (Maori who fought for a Maori king, as opposed to British rule) built a gunfighter pā named Rangiriri betwixt the Waikato River and Lake Kopuera in 1863, which resembled a giant trench, albeit on high ground with a vast array of supporting earthworks. Placing anything too close to a waterway that was navigable for the Royal Navy was a bad idea, however, and this pā was duly destroyed by shipboard Armstrong Guns.

|

Gunfighter pā were sometimes built in areas of no strategic value, far from populated areas, so as to invite the British to come out and play. One such example was the largest gunfighter pā to have existed in New Zealand, Ruapekapeka. Built in 1845, this fort was named after the Maori word for "bats' nests," referring to the dugouts that served as the labyrinthine entrances to the fort's inner shelters.

Ruapekapeka was the site of the last battle of the Flagstaff War (1845-1846), a conflict that centered on the actions of Maori chief Hone Heke (1807-1850), who had an issue with the British flag flying on Flagstaff Hill in the town of Kororāreka. Hone Heke had given the flagstaff to James Busby (1802-1871) British Resident (kind of like a governor, but one they didn't want to call a "governor") as a gift after the signing of a treaty, but that treaty turned out not to mean what Hone Heke thought it meant, and the flagstaff was cut down by the Maori in protest. The British raised the flag shortly thereafter, whereupon it was cut down again...and raised, and cut down. Childish? Perhaps, but this nonsense morphed into a full-blown war.

Alerted as to the antagonizing existence of Ruapekapeka in December of 1845, a British colonial force under the command of a Lieutenant Colonel Despard spent two weeks advancing thereto with eleven pieces of artillery and two of those ridiculous Congreve Rocket tubes. A semi-siege (the British didn't have enough men to completely surround the pā) and bombardment followed for the next few weeks, followed by some spirited, and no doubt fun, skirmishing. |

|

Storming of the pā at Ruapekapeka, 11th January 1846, and what Ruapekapeka looks like today: Better than many of the American Civil War-era earthworks that still exist in my neck o' the woods! Storming of the pā at Ruapekapeka, 11th January 1846, and what Ruapekapeka looks like today: Better than many of the American Civil War-era earthworks that still exist in my neck o' the woods! |

|

Ruapekapeka was unusual in that it was armed with artillery, though it was some pretty sad, insignificant artillery: A "deck gun," designed for shipboard use, and some sort of field piece. The former was almost immediately taken out of action by accurate British fire, and the latter was mostly useless from the start due to lack of powder and munitions.

A British foraging party noted that the maori fort seemed awfully quiet on the morning of Sunday, January 11, 1846. The British pushed down part of the undefended outer wall and entered the fort, finding it nearly deserted: Many of the Maori were Christian, and had left the pā to go to church, expecting their equally Christian foe to respect this ecclesiastical pursuit and not attack on a Sunday morning for crying out loud. Surprise!

|

|

|

As further British colonial troops poured into the front of the fort, the Maori proceeded to pour into the rear of the fort, and a vicious, if brief, battle ensued. The Maori were shortly ejected from their pā, leaving behind some 60 dead: The preceding British bombardment reportedly caused zero of these casualties, as the defenders had been protected in bombproof shelters. After spending some time marveling at the engineering of Ruapekapeka, the British burnt it to the ground.

Today, the Maori still consider themselves to have been ultimately unvanquished by the British. This may be debatable, but the gunfighter pā was certainly a unique phenomenon in the joyous history of European colonialism. |

|

|