|

Fort Glanville

Adelaide, Australia

|

|

|

Constructed: 1878-1882

Used by: Australia

Also known as: Semaphore Battery

Conflicts in which it participated: None

|

There are few land masses on earth that don't have at least a couple of starforts built thereupon, and Australia is one of them. Antarctica and Greenland have a murderously inhospitable climate as an excuse, and while much of Australia is indeed murderously inhospitable, why would a colony of one of the world's leading starfort exporters not have starforts? Two reasons: Distance, and timing.

Australia is far away from everything. London to Brisbane is a 10,262-mile trip, and that's a direct route by air. Add another thousand miles or so for a sea journey, and you still wouldn't be there yet. |

|

|

|

Dutch and Spanish explorers discovered Australia independently of one another in 1606, but did not elect to claim it for their motherlands (although the Dutch did name it New Holland), much less attempt to colonize. Why would they? It was the Age of Discovery, they had discovered it, and surely there were lands awaiting discovery that weren't many thousands of miles away from anything else. England finally stumbled across the continent in 1770, when James Cook (1728-1779) sailed along and mapped its east coast: He named it New South Wales, and claimed the whole mess for Great Britain.

|

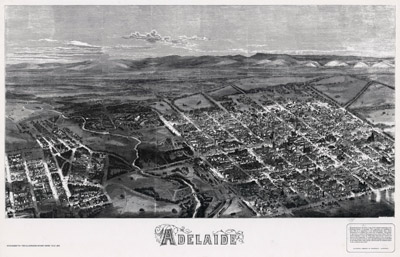

The city of Adelaide, as printed in the July, 1876 issue of Illustrated Sydney News. Sadly, this map predates Fort Glanville, so don't bother squinting at it, looking for forts. You could click on it and admire it anyway, because it's quite lovely even if fortless. The city of Adelaide, as printed in the July, 1876 issue of Illustrated Sydney News. Sadly, this map predates Fort Glanville, so don't bother squinting at it, looking for forts. You could click on it and admire it anyway, because it's quite lovely even if fortless. |

|

Making the bemused locals into instant subjects of the crown by claiming a landmass and actually doing anything with or upon that landmass are two different things, and Great Britain may never have taken the next step with Australia had it not lost its American colonies, with the conclusion of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783).

One of the main reasons Great Britain even had a colony in the New World was so they could transport their unwanted persons far, far away, and it must have dawned on some British civil servant that when it came to relocating wretched refuse, the further the better. Australia would be Great Britain's new dumping ground! |

|

|

Adelaide was founded as an English settlement in February of 1836. Named for Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen (1792-1849), Queen of the United Kingdom and Hanover (and wife of England's King William IV (1765-1837)), this city does not share the "convict settlement history" of Australia's other major cities: In most cases, when convicts landed on Australia they were instantly given a land grant, which was swell, but if everybody's a landowner, who are the laborers? Australia's original inhabitants, known now by the catch-all name of Aborigines, were busy hacking their lungs out thanks to all of the weird diseases that the British brought with them, so they were no help. Land in Adelaide was sold at a high enough rate that newcomers couldn't afford it, and were thus forced into working class status.

|

So we've established that Australia is really really far away from everything that was important in the Age of Discovery, which means Europe. Once the British had established themselves down under, there wasn't a whole lot of concern about coastal defense, because whom, with the naval capability, would want to mess with Australia?

As it turned out the answer was nobody (except the Japanese in the Second World War (1939-1945), but let's not get ahead of ourselves), but tensions betwixt Great Britain and the Russian Empire in the mid-19th century opened up whole new arenas of concern.

|

|

Circa 1882, a merry gun crew (the couple holding hands seems particularly carefree and gay) poses with their Armstrong 10" RML (Rifled Muzzle Loading) gun. Fort Glanville is unusual for Starforts.com in that photography existed when it was first built! Circa 1882, a merry gun crew (the couple holding hands seems particularly carefree and gay) poses with their Armstrong 10" RML (Rifled Muzzle Loading) gun. Fort Glanville is unusual for Starforts.com in that photography existed when it was first built! |

|

Strange bedfellows Britain, France, the Ottoman Empire and Sardinia allied to take on Russia in the Crimean War (1853-1856). This conflict ended in a humiliating defeat for Russia, which included the destruction of its Black Sea Fleet, leaving much of its southern border unprotected. It would certainly have been easy to come to the conclusion that Russia had an interest in doing some damage to British interests...perhaps somewhere far from the semi-all-powerful Royal Navy, but not so far from Russia's new Pacific naval base at Vladivostok? Such were the frenzied thoughts of many Australians, and it's hard to fault their logic.

As part of the British Empire, Australia expected the motherland to see to its defense...but the British Empire was a vast one, with commitments all over the world and only so many pasty British guys with rifles to guard it all. There were various brief local enthusiasms for organizing militias around Australia, but marching about is tiring, and actual defensive structures are expensive.

|

One of Fort Glanville's two Armstrong 10" RML guns. This gun could be loaded manually, which exposed two crewmembers to incoming fire, or with the Armstrong Mechanical Loader, a bit of which I believe we see at the gun's muzzle, which was probably a safer but slower means by which to reload. |

|

In 1851, a local entrepreneur named George Coppin (1819-1906) built a two-story, timber hotel on the easternmost extent of land in the Adelaide area. He named the hotel White Horse Cellars, and raised a flag on a huge pole next to it, to entice shipboard folk approaching Adelaide Harbor. Communication via flag-waggling was (and still is) known as semaphore, so that was the name that this part of Adelaide adopted.

Semaphore was identified as a good spot for a coastal defensive work early on, though looking at the imagery today, it's difficult to see why. |

|

|

Both Fort Glanville and Fort Largs, of which we'll learn in a bit, certainly seem to have been slammed down on the coast without particular regard for strategy...there are no inlets into Adelaide Harbor in the immediate vicinity, for example. But I do recognize that things probably looked different in the mid-19th century than they do now, that shipping lanes were locally understood and impossible to presently see on Google Maps, and that the folks making siting decisions likely had a handle on things. Probably. A jetty was built at Semaphore in 1860, which did make it South Australia's main point of entry...so, okay, it makes sense as a strategic location. You win, Australia.

An event that took place in 1862 illustrated Australia's vulnerability to anyone who cared to note it. The Russian ship Svetlana, a French-built, 40-gun steam frigate, paid a friendly visit to Melbourne. Sailing past whatever battery was then mounted at the entrance to Port Phillip Bay on Queenscliff, it did the standard thing a warship did in such situations, which was to fire a salute. The proper response to such a salute was to fire an answering salute, but the battery was presently not supplied with any gunpowder, which most folks will agree is a necessary ingredient for the use of artillery. Whether the Svetlana steamed home and reported this embarassing Australian situation is anybody's guess, but this event's import was not lost on those interested in defending Australia's shores.

In 1864 Commodore Sir Walter Wiseman, Commander of Britain's Australian Station, suggested that three fixed fortifications, in addition to four gunboats, would be necessary to defend Adelaide should the Russian Navy come to call with ill intent. The Australian government coughed up £20,000 for coastal defenses, and site preparations were made for a fortification at Semaphore. Two 9-inch guns were purchased for the forthcoming fort, but whatever immediate crisis had precipitated this momentary clarity of thought passed, and nothing was built.

|

In 1870, Great Britain withdrew what few troops it had stationed in Australia, which island nation finally realized that it would have to see to its own defense. The states of South Australia (in which Adelaide exists), New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland asked Great Britain's War Department to send one Lieutenant General Sir William Francis Drummond Jervois (1821-1897) to Australia to determine their defensive needs. I know what you're thinking: The Lieutenant General Sir William Francis Drummond Jervois? Yes! The renowned coastal fortifications expert Lieutenant General Sir William Francis Drummond Jervois.

|

|

Fort Glanville's parade ground around 1900, featuring the fort's mascot...which may be some kind of Australian man-eating warthog, but is probably just a canine of some sort. Fort Glanville's parade ground around 1900, featuring the fort's mascot...which may be some kind of Australian man-eating warthog, but is probably just a canine of some sort. |

|

Jervois had been Britain's Governor of the Straits Settlements, which included Singapore, since 1875. While he was touring Australia with an eye towards suggesting defenses in 1877, he was appointed Governor of South Australia: Surprise! It turned out that during his tenure as Governor of the Straits Settlements, he had quelled a Malay uprising, but then "interfered" on the Malay mainland, in some manner that displeased the Colonial Office. Since Jervois was already on a mission with the express purpose of interfering on the Australian mainland, he must have seemed like a slam-dunk for Governor of South Australia.

Lieutenant General Sir William Francis Drummond Jervois (GCMG CB FRS)'s suggestions for Adelaide's defense sounded a lot like those of Sir Walter Wiseman some thirteen years previously: Three coastal fortifications with "naval elements" in support, along with a military road connecting the forts and field gun emplacements. He also suggested the establishment of a futuristic electro-contact torpedo station on Torrens Island, inside Adelaide's inner harbor. Plans for the fortification of Adelaide had come and gone in the past, but with Jervois as Governor, things actually happened this time: The Military Forces Act was passed in 1878, which provided for a permanent military force, including an artillery unit...and, finally, the money and will to build coastal fortifications!

|

The only reason I dared to include Fort Glanville amongst the stellar starforts of Starforts.com is that it has a caponniere, or as the English called them, caponier. It's the little weenie that sticks out at the top right of the pic at the head of this page, and serves as means by which a fort's walls might be cleansed of attacking infantry via a judicious application of rifle fire. The only reason I dared to include Fort Glanville amongst the stellar starforts of Starforts.com is that it has a caponniere, or as the English called them, caponier. It's the little weenie that sticks out at the top right of the pic at the head of this page, and serves as means by which a fort's walls might be cleansed of attacking infantry via a judicious application of rifle fire. |

|

Semaphore, by this point, had developed into something more impressive than just a hotel with a really big flagpole. In addition to the all-important jetty, a signal station was built there in 1872, and a time ball tower was added in 1875. This was a time-signaling device for mariners, whereby a large metal or wooden painted ball, impaled on a pole atop a structure of some sort, would visibly drop at predetermined times, by which signal a ship could set its chronometers.

Traveling with Sir Jervois on his mission of enfortification was British Major Peter Scratchley (1835-1885), a "special commissioner" for Great Britain and New Guinea...but most importantly, here was a guy who knew how to design forts. |

|

|

Scratchley had served with the British Army in the Crimean War and Indian Mutiny of 1857. The Jervois-Scratchley Reports of 1877 detailed the need for several coastal fortifications, five of which were designed by Scratchley: Fort Glanville, Bare Island Fort in Botany Bay, Fort Scratchley in New South Wales, Fort Lytton in Brisbane and Fort Queenscliff in Victoria...click their names to see the forts, they're all batteries, like Fort Glanville...though arguably less forty than Fort Glanville. Which brings us headfirst into the unpleasant brick wall of truth that is, Fort Glanville is no starfort, but a defensible battery. In my eyes it certainly qualifies as a fort, as opposed to a battery, as it is an enclosed entity, with a caponniere in place to help defend it from infantry attack. Please address all starfort selection-related complaints to dontcare@starforts.com. |

Construction began on Fort Glanville in 1878. Its name came from nearby Glanville Hall, home of Captain John Hart (1809-1873), who served three non-consecutive terms as Premier of South Australia...not the Governor, but the "head of government." Hart had named the property after his mother, whose maiden name had been Glanville.

Building what was initially known as Semaphore Battery took four years, but two 10" guns were mounted by January of 1880, and the fort was considered operational at that time.

|

|

|

|

The coastal fortification of our current interest was renamed South Battery during its construction, but by the time of its official opening ceremony on October 2, 1880, it was named Fort Glanville. The original contract for building our fort had been £15,893 12s 7d (whatever an s and a d are), but when all was said and done upon completion in 1882, its total cost had been £36,000. Has anything in the history of anything ever been built for less than the price that was originally agreed upon? Certainly no forts have, in my experience.

Fort Glanville's big punch was to be delivered by two Armstrong 10" RML (rifled muzzle-loading) guns, and two 64-pounder RML guns on field carriages graced its two smaller emplacements. Unhappily, one of the two 10" guns proved to be "faulty" on its first outing, which embarassingly took place during the fort's opening ceremony. Was this faulty gun replaced? It doesn't seem so!

When operational, Fort Glanville was manned with a number of soldiers that varied over time from 56 to 108. Despite its caponniere, our fort wasn't intended to defend itself, but Port Adelaide and the Semaphore anchorage...when designed, it was expected that a force of field artillery, cavalry and infantry would defend Fort Glanville from direct attack. This defensive force may or may not have ever actually existed.

|

Pickelhaubened reenactors loading one of Fort Glanville's two 64-pounder RML guns. Pickelhaubened reenactors loading one of Fort Glanville's two 64-pounder RML guns. |

|

As one might expect, Fort Glanville was supported by a series of interior and exterior structures and tunnels. The two-floored barracks was studded with firing embrasures; There was a laboratory in the fort, where gun charges would be prepared. The caponniere was accessed via a tunnel with a dogleg, to mitigate notional blast damage.

By the end of the 1880's, Fort Glanville was sidelined by Fort Largs, a smaller fort that had been built to the north. More modern guns with a greater range were mounted at Largs, and changes in the Port River meant that the anchorage at Semaphore was no longer a strategic asset in need of protection. |

|

|

Despite being eclipsed by the littler Fort Largs, Fort Glanville served as the headquarters for South Australia's permanent military force through the 1890's. Somebody must have thought our fort would serve a purpose going forward, as in 1895 there were plans to replace its 64-pounder guns, whose wooden carriages had rotted to uselessness, with a couple of modern six-inch guns...but this scheme never came to fruition. The fort was downgraded to caretaker status in 1901, with no permanent force stationed therein.

Through much of the 20th century, Fort Glanville joined the status of many a fortification: Big Expensive-to-Maintain Useless Thing For Which Nobody Wishes to Take Responsibility. The mounts for its 10" guns were sold for scrap in the 1930's, but the gun tubes were left in place, seeing as they were so very unwieldy. The fort was used to store ammunition on a few occasions, housed refugees for a brief period during the Second World War (1939-1945) and was utilized as a "caravan and camping park" in the 1950's. Fortunately Fort Glanville was named an Historic Relic in 1972, and restoration work began. Since the 10"- and 64-pounder gun tubes had been left in place, new carriages were built for them and, in a ceremony held on the 100th anniversary of Fort Glanville's guns first being fired in 1880, one of the 64-pounders was fired. The fort opened to the public in 1981.

Today, the Fort Glanville Conservation Park showcases the best-preserved colonial fortification in Australia, complete with its original armament...and boasts a living history program, in which reenactors march about, being acutely resplendent in their Victorian, pith-helmeted uniforms.

|

|

|

|

The majestic, if demonstrably shrimpy, interior of Fort Largs. The majestic, if demonstrably shrimpy, interior of Fort Largs. |

|

|

|

|

|

|