|

Fort de Chartres

Prairie du Rocher, Illinois, United States

|

|

|

Constructed: 1720, 1725, 1753-1756

(Reconstructed 1930's & 1970's)

Used by: France, Great Britain

Conflicts in which it participated:

None

Also known as: Fort Cavendish

|

Through much of the 17th century, French explorers and missionaries from Canada made their way through the Louisiana and Illinois Territories, mapping and claiming everything as they went. While the local Native Americans would have surely taken issue with the idea that the French were claiming this land as their own, the white dudes were the ones making the maps, so claimed it was.

In the interest of keeping the English confined to their thirteen colonies on the Atlantic coast and out of the continent's western reaches, the French planned a series of forts to prevent English incursions. |

|

|

|

The first of these was Fort St. Louis du Rocher, built in 1682 on a hill commanding the Illinois River, in what is today central Illinois. This was a somewhat flimsy-sounding wooden palisade surrounding a few buildings, but in a land with no artillery, the wooden palisade is king. At least until an attacker discovers that there's such a thing as fire.

The French wanted to develop their colony of New France, and in January of 1718 granted a trade monopoly to the Compagnie de l'Occident, which sold shares in the Mississippi Company to investors. The intent was to mine precious metals and reap a fortune, which would in turn solidify the French position in America. Later that year, work commenced on a fort that would protect the Compagnie's interests in the region: This would be Fort de Chartres.

|

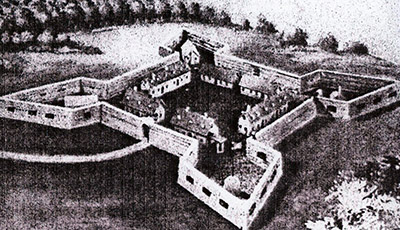

This is not the earliest iteration of Fort de Chartres. There would ultimately be three Fort de Chartreses, four if you include the reproduction that stands today. This is a drawing of the mighty Fort de Chartres No. 2. |

|

The first Fort de Chartres was a wooden affair, built from 1718 to 1720 by a French military officer from New Orleans named Pierre Dugué de Boisbriand (1675-1736) and his merry band. The initial Fort de Chartres was a square palisade of logs, with bastions at opposite corners...kind of a pre-starfort. Starfort or not, it served as the administrative headquarters for France's Illinois Country.

Just about as destructive to a wood fort as fire is the opposite of fire, which is water. Built on the banks of the ever-throbbing Mississippi, within five years Fort de Chartres had been damaged severely by those raging waters. |

|

|

Construction of Fort de Chartres Version 2.0 began in 1725 at a slight remove from the Mississippi, though still on the river's flood plain...the French wanted to command the river, but did not particularly want their fortifications to be swallowed by that river. Though the deterioration process took longer, Version 2.0 suffered much the same fate as Version 1.0 and by 1742 Fort de Chartres was again considered to be in too poor a state to function properly.

|

The primary reason that Fort de Chartres was being maintained on the cheap (wooden forts are way cheaper than masonry forts, as one might imagine) was that this whole enterprise was privately operated, by the aforementioned Compagnie de l'Occident...and private corporations, no matter how well-funded, did not tend to built world-class starforts. This hurdle was leapt in the 1730's, however, as the Compagnie went out of business and ownership of the region reverted to the French crown!

|

|

|

|

When Fort de Chartres 2.0 was determined to be unfit for a garrison, those men had been moved to Kakaskia, another French settlement 18 miles to the south. The French government in New Orleans wanted to permanently relocate the Illinois Country's administrative HQ to Kakaskia, but there was no starfort there (though there would later be a Fort Kakaskia, it was really just an earthen redoubt: "Fort" indeed!). Wiser heads fortunately prevailed and a Fort de Chartres Version 3.0, to be constructed of glorious stone close to the locations of the previous Forts de Chartres, was decided to be the best course of action.

|

Fort de Chartres' Powder Magazine is "thought to be" the oldest standing structure in the state of Illinois. At top is that magazine prior to 1917, when it was restored to it's present state of grace, seen below. Fort de Chartres' Powder Magazine is "thought to be" the oldest standing structure in the state of Illinois. At top is that magazine prior to 1917, when it was restored to it's present state of grace, seen below. |

|

The third Fort de Chartres is the one semi-represented by today's existing reconstruction. Work began in 1753 on this beauty, which, when more or less completed in 1756, had 15-foot-high, three-foot-thick limestone walls, surrounding a four-acre parade ground. The French built their newest, pointiest starfort just in time to heroically...

...surrender it without a fight to the British! The French and Indian War (1756-1763), known to the British as the Seven Years' War, did not reach the Illinois Country, but the Treaty of Paris that ended that war transferred most of France's North American holdings to Great Britain...including Fort de Chartres.

The British Army's first priority when taking possession of something that had previously belonged to the French was to rename it as quickly as possible, lest an Englishman be forced to pronounce a word with a distasteful silent letter at the end of it. Interestingly, the Royal Navy felt less of a compulsion to do this: Captured French ships were occasionally renamed, but usually not: It served the Navy's purpose to parade their captures around with as much fanfare as possible, whereas it was much more difficult to sail a starfort from place to place in a haughty manner...but really, I think it had more to do with British Army guys not wanting to figure out how to pronounce French words. |

|

|

The Illinois Country east of the Mississippi River was transferred to Great Britain after the war, while France had given the region's western reaches to Spain in 1762. When the British took control of their glorious new lands-in-the-middle-of-nowhere, they gave anyone who preferred to live under French authority 18 months to make like trees and leave. Many of whom headed for St. Louis or New Orleans.

|

The British had a difficult time even getting to their new starfort, but a small detachment finally made it there in October of 1765. The 34th Regiment of Foot renamed Fort de Chartres Fort Cavendish, after their commanding officer, and then ordered all French Canadian settlers still in the area to leave or get a special license to remain.

The 34th was replaced by the 18th (Royal Irish) Regiment in 1768. When the 34th left, so did the name Fort Cavendish: The name Fort de Chartres was immediately restored, and has remained in place, as is only right and proper, from that moment on.

Ultimately, the British discovered why there had been so many Forts de Chartres: The river. By 1772 Fort de Chartres's southern wall and bastion had fallen into the impolitely demanding Mississippi, and the British garrison departed for Kakaskia, where they remained until May of 1776.

Abandoned, our starfort deteriorated at a pace one might expect. In the 1820's locals noted that there were trees growing in the fort's walls, a situation they remedied by making off with stones from those walls to use as building materials. |

|

Here's something you don't see very often on starforts in the United States: A guérite! Here's something you don't see very often on starforts in the United States: A guérite! |

|

By 1900 the walls of Fort de Chartres were gone, their stones integrated into the buildings of the nearby town of Prairie du Rocher. The only clue that a glorious starfort had once existed there were the remains of the Powder Magazine, whose stones were assumedly too difficult for the thieving townsfolk to cart away.

|

Fort de Chartres' East Bastion, and that Powder Magazine again. Thanks for the great pic, Fortwiki.com! Fort de Chartres' East Bastion, and that Powder Magazine again. Thanks for the great pic, Fortwiki.com! |

|

In 1913, the State of Illinois acquired what was left of Fort de Chartres, and endeavored to rebuild the Powder Magazine in 1917. An effort in the 1920's located the fort's walls and inner structures, and all of the buildings in Prairie du Rocher were pulled down for building materials, with which the fort was reconstructed. Just kidding.

The Great Depression brought with it many wonderful things, the foremost example being the Works Progress Administration. This US governmental agency was dedicated to employing millions of relatively unskilled folks, putting them to the work of rebuilding America's infrastructure. Through the 1930's, the WPA was responsible for countless new schools, roads, parks, bridges...and starforts! |

|

|

US State Governors were given some say as to what construction projects would be undertaken in their states, and in at least two cases, starfort reconstruction was the result: Fort Frederick in Maryland was another beneficiary of the WPA. Through the 1930's, Fort de Chartres' gateway, two stone interior structures and a bake oven were built atop the remains of fort Version 3.0. The fort's walls were partially rebuilt in 1989, and the frames of more interior buildings were added, atop their original foundations. Today Fort de Chartres houses a museum and a gift shop, and every June a Rendezvous, a celebration of frontier French and Indian culture, is held at the fort...and April brings the annual Fort de Chartres Colonial Trade Faire, Musket and Rifle Frolic. The Mississippi is mostly tamed by modern levees, but a flood in 1993 breached those levees, and river water yet again lapped at the walls of Fort de Chartres. You would think someone would have gotten the hint by now, and built their starfort in the Rocky Mountains instead.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|