|

Fort Charlotte

Lerwick, Shetland Islands, Scotland

|

|

|

Constructed: 1781-1783

Used by: England

Conflicts in which it participated (in an earlier incarnation):

Second & Third Anglo-Dutch Wars

|

The Shetland Islands are known for their ponies, not their trees.

Located where it is in the Extremely North Atlantic, the Shetland Islands are distinctly lacking in trees...which the rest of us take for granted, but go to a place without trees, and the first thing you'd likely think is, "where are all the trees?!?" This marked lack of naturally-occurring wood meant that the folks who lived on the Shetlands prior to the Official Start of Timekeeping, the birth of one Jesus H. Christ (0-33AD), were forced to build their important structures out of stone, instead of the timber that most of the rest of the world utilized. This means that the things they built actually lasted, and there are over 5,000 recognized archaeological sites on Shetland that date to as early as the 5th century BC. |

|

|

|

How many of these ancient sites were starforts? Well, admittedly none of them. But I mention them because they make for an excellent starting point in our ongoing discussion related to starforts. So, here we go: Starforts.

Northern Europe's seafaring nations, by which I mean the Scandanavian peoples, were the first outlanders to develop a possessive interest in the Shetland Islands. As early as the 8th century, Vikings were coming to stay, and used the islands as a staging ground for raids against the Scottish and Norwegian coasts. Understandably taking issue with this arrangement, Scotland maneuvered its way onto the lesser Shetland Islands, effectively surrounding the mainland. By 1470 a combination of dynastic intermarriages and good old-fashioned sneakiness had the Shetland Islands securely in the grasp of Scotland's King James III (1452-1488).

The Dutch, however, were having none of it. They had developed a fishin' 'n' tradin' presence in Bressay Sound, which separates the island of Bressay from Shetland's Mainland, in the 15th century, and the locals saw no reason not to trade with these nautical Dutchmen, despite official Scottish displeasure at this commerce.

|

|

|

The Dutch East India Company also used Bressay Sound as an anchorage for its fleets returning from the Far East into the 17th century...which seems like an awfully long way around, until one notes that traversing the English Channel under such circumstances would be practically begging the English Navy to capture and/or sink all of the cool things that the Dutch were trying to bring home from India.

From Bressay Sound, the Dutch Navy could escort the Dutch East India ships safely back to Holland.

In 1650, the Most Temporary Commonwealth of England, in the person of His Majesty Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658), Lord Protector of England, invaded Scotland. Having subdued the Scots two years later, and despite busily fighting just about everybody else everywhere, Cromwell somehow found the energy to declare war on Holland, over the two nations' conflicting trade routes. |

|

|

Seeing as the Dutch were so historically comfortable in Bressay Sound, an English fort was built at Lerwick in 1653. No trace of this fort remains today, but it's fair to assume that it was at least passingly starfortish, in that a) it existed to command the sound with artillery from atop mighty cliffs, and b) everybody and their uncle was building starforts, albeit of a slapdashedly earthwork nature, during the English Civil War (1642-1651).

The First Anglo-Dutch War (1652-1654) was fought solely betwixt the belligerent nations' navies, and settled not a thing that Cromwell had hoped to address. Fortunately for war-lovin' Europeans in the 17th (and 16th and 18th and 19th) century, one never had to wait long for another chance to cover oneself with warrish glory, and the Second Anglo-Dutch War kicked off in 1665, for much the same reasons that there had been a First Anglo-Dutch War. Recently restored to his most regal ascendancy, England's King Charles II (1630-1685) appointed Master Mason John Mylne Junior (1611-1667) to construct a new fort at Lerwick, at the same location as the wickedly Cromwellian 1653 fort. £28,000 were earmarked for the construction of this most important fortification.

|

Lerwick's second fort was ploygonal in design (read: Starfort), and mostly built of earth and timber. The war was so speedy (it concluded in 1667, with the Royal Navy having gotten a pounding) that Junior never had a chance to finish his fort...but that was okay, because whatever had been built was spiny-looking to a degree that a Dutch naval force did take note of its presence and decided not to mess with it.

|

|

Fort Charlotte's majestic eastern extent today, brought to us thanks to some Google Street View action. |

|

With the war over, our unfinished fort was abandoned. Because what kind of madman would finish a fort in peacetime?!?...persons who cleverly surmised that there just might be a Third Anglo-Dutch War in short order, would have finished building their fort commanding Bressay Sound. But it would appear that Charles II was not that clever person, and when the third Anglo-Dutch go-round lurched into being in 1672 (this time with France and England ill-advisedly taking on the Dutch), there was nobody manning the fort at Lerwick to prevent a Dutch landing party from burning Junior's collection of unfinished earthen timbers, which occurred in 1673.

|

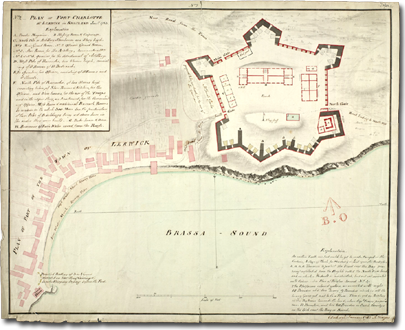

An absolutely flippin' gorgeous map of Fort Charlotte by Andrew Frazer, 1783. You can buy your copy from the National Library of Scotland, here! |

|

As bad as things were for England in the 1670's, what with the repeated losing of relatively unimportant wars with the Dutch, things looked even bleaker a century later, when the Royal Navy was regularly trading shots with the Dutch, French, Spanish and Americans. This was thanks to the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), which renewed English fears of a seaborne, invading enemy. A desperate scramble to reinforce countless long-ignored coastal fortifications brought England back to Lerwick, where a new and vastly more impressive starfort was planned.

Fort Charlotte, whose stone ramparts followed the polygonal design of the 1665 fort, was named for Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1744-1818), the wife of England's King George III (1738-1820). |

|

|

Fort Charlotte's starfortiest features are its three bastions, arranged to protect the fort's landward side. Facing the sound is a zig-zaggy parapet wall, upon which were mounted twelve 18-pounder guns...this layout was thought more conducive to covering a body of water, as guns so arranged could, in theory, be traversed to cover more water than those in bastions: Fort Pike, guarding New Orleans, has a vaguely similar gundeck covering the Rigolets Pass.

|

The American Navy never got around to marauding their way through the Shetland Islands, but Fort Charlotte was kept ready for all comers. It was garrisoned with 100 men during the 1793 war with Revolutionary France, and its guns were upgraded during the War of 1812 (1812-1815) as a measure against swift-sailing privateers.

When the wars stopped coming with such alarming frequency, Fort Charlotte was used as Lerwick's jail and courthouse, a capacity in which it served from 1837 to 1875. Upon the realization that heavy guns weren't needed to defend a prison against jailbreaks, Fort Charlotte's artillery was removed in 1855. |

|

One of Fort Charlotte's mighty guns, threatening one of Bressay Sound's ubiquitous ferries. International law compels me to include this text under this lovely picture: ©photomalt/123RF.COM |

|

As a Coast Guard station, customs house, drill station for the Royal Naval Reserve and drill hall for the Territorial Army, Fort Charlotte soldiered on through the 20th century. It was reactivated during the Second World War (1939-1945), solely so that some new (and likely surpassingly unattractive) concrete buildings could be built within its walls...all of which were fortunately removed after 1945.

Though in its heyday Fort Charlotte loomed belligerently over the sound, land reclamation means that it is now mostly surrounded by the town of Lerwick. In addition to being the UK's northernmost starfort, it is one of only three 17th/18th century Scottish military entities that still serves as an active military base, for the Territorial Army.

Thirty five thousand embarassed thanks to the kind person who alerted us to Fort Charlotte...I'm sad to report that I can't seem to find who that nice person WAS, perhaps they'll remind me, so that I can make them starfort-famous by giving them a shoutout? Thank you, kind and thoughtful person, whomever you are.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|