|

Fort Beauséjour

Aulac, New Brunswick, Canada

|

|

|

Constructed: 1750-1753

Used by: France, Great Britain

Conflicts in which it participated:

French and Indian War,

American Revolutionary War

Also known as: Fort Cumberland

|

The Acadians, French settlers in the New World starting at the beginning of the 17th century, were the Palestinians of the Americas. They had a historical claim on the lands that France and Britain fought over for 200 years, but neither of the warring parties really wanted them to be where they were (much less the Indians who had been there first, although they and the Acadians did seem to get along relatively well), and the Acadians were eventually dispersed in various directions, after being forced to endure unnecessary hardship. |

|

|

|

The Isthmus of Chignecto is that strip of land that connects Nova Scotia with New Brunswick, and thus the rest of Canada. This area was immensely important to both France and Great Britain, but the Acadians got to it first, and settled all over the place. Pre-American forces led by Benjamin Church (1639-1718) came to Chignecto and bashed at whatever Acadian was unfortunate enough to be visible during both King William's War (1688-1697) and Queen Anne's War (1702-1713)...the Treaty of Utrecht, which ended Queen Anne's War, ceded Acadia to Great Britain.

|

Much coolness remains at Fort Beauséjour. |

|

The precise boundaries of where French and English territories in Canada started and ended weren't spelled out in the treaty, however, and both powers claimed the Isthmus of Chignecto. Acadian settlers continued to come to the area, many having been displaced from Nova Scotia, where the British were busily Britaining up by displacing Acadians! Acadians for the most part considered themselves neutral in the interminable goings-on betwixt the crowned heads of Europe, but the British most certainly didn't trust them...and niether did the French.

The French regularly demanded loyalty oaths of the Acadians, to which these poor folks |

|

|

would occasionally submit themselves, but by & large Acadians refused to march off to battle in the service of France, which made them worthy of suspicion in squinty French eyes.

In 1749 Halifax, Nova Scotia was founded by Great Britain, which set off a new wave of Acadian displacement. Many of the families chased out of Nova Scotia settled on the Isthmus of Chignecto, and by the early 1750s around 3,000 Acadians called Chignecto home.

Just to make sure nobody had a chance to get settled or relax in any way, British Colonel Charles Lawrence (1709-1760) built Fort Lawrence at the village of Beaubassin in the Spring of 1750 (don't bother looking, there's nothing there now). This was smack dab in the middle of where the poor Acadians were trying to eke out an existence on the Isthmus of Chignecto, and was a direct challenge to the French in the region. In November of 1750 the French countered Fort Lawrence by starting work on a fort at Pointe-à-Beauséjour, a spot on the Missaguash river at which the French military had been hanging out (without bothering to build anything permanent) since 1744.

|

Overseen by Claude-Antoine de Bermen de La Martinière (1700-1761), work on Fort Beauséjour advanced slowly...so much so that it remained unfinished when the French and Indian War (1754-1763) broke out. A British force commanded by Lieutenant General Robert Monckton (1726-1782), consisting of 270 British regulars and nearly 2,000 colonial troops from New England, arrived on the Isthmus on June 2, 1755, and began grinding their way towards the fort of our current interest. Monckton expected over 1,000 Acadian troops in addition to the 150-man French

|

|

A model of Fort Beauséjour in its glory days at what looks like a very cool museum there! |

|

garrison to be defending Fort Beauséjour, but after a few days of being bombarded, the French lowered their flag in surrender, and out marched only around 300 Acadians (three of whom had been killed during the siege) along with the garrison. On June 16, 1755, the British flag was raised over Fort Beauséjour, which was officially renamed Fort Cumberland. Robert Monckton went on to do various other notable things in the New World (many of which involved persecuting Acadians), and received the highest posthumous honor imaginable in 1793: He had a starfort named after him! As you may have guessed, it was called Fort Monckton. Which seems obvious, but the town that was named after the dude, just over 30 miles west of Fort Beauséjour, is spelled Moncton. The British spent the rest of the war expanding Fort Cumberland and chasing Acadians around, but the French never came to restore their fort's name, which was, I'm sure we can all agree, much cooler. Redcoats garrisoned the fort until 1768, but by then Acadia was finished, and French claims to the region were over. The British returned to Fort Cumberland again in 1776, however, thanks to the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783).

|

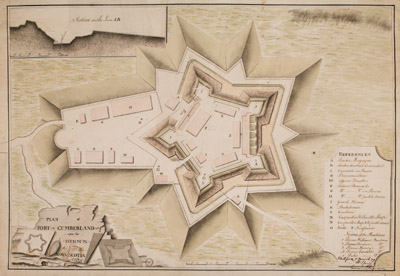

Fort Cumberland, 1778. Click on it, it's huge. |

|

In the standard British fashion of renaming things whose original names they couldn't pronounce, the Isthmus of Chignecto was by now known as the Isthmus of Nova Scotia. Whatever it was called, by the 1770's the isthmus and most of the rest of Nova Scotia was populated with many families originally from New England, whose devotion to the King of England was iffy at best.

When the British Royal Fencible American Regiment of Foot arrived at Fort Cumberland in the summer of 1776, the fort was in the condition one might expect after eight summers and winters of abandonment. Along with a garrison of 200 loyalist troops, the Fencibles set about reestablishing the starfort's pointy edges, but the locals were |

|

|

unwilling to help in the effort, even going as far as trying to convince the British troops to defect.

Enter Jonathan Eddy (1726-1804), a man who had fought for the British during the French & Indian War, and who now lived not far from Fort Cumberland. A pal of American Founding Fathers Samuel Adams (1722-1803) and George Washington (1732-1799), Eddy was a fervent supporter of the cause of American independence. His bold plan was to wrest all of Nova Scotia from the British, adding "another stripe to the American flag." Even though thirteen stripes are plenty, Eddy felt compelled to gather what sounds like a particularly ragtag bunch of 180 of his neighbors, natives (somehow there were still some Indians living in this land of frequent Europeans) and other suggestible Nova Scotians, arm them with muskets that the State of Massachusetts had generously provided for this crazed enterprise, and pushed them towards Fort Cumberland on November 13, 1776.

An attack that was repulsed. Had Eddy access to this website, he would certainly have understood the futility of attacking a manned and properly maintained starfort without air support, but due to the tragic lack of the Internet, he directed two more failed attacks on Fort Cumberland over the next ten days. Finally the British 16-gun sloop HMS Vulture appeared on November 28, adding its Royal Marines to the defense of Fort Cumberland, which induced Eddy to give up on his grand plan of conquering Nova Scotia with less than 200 men. (The HMS Vulture was the ship on which Benedict Arnold (1741-1801) would escape after his failed attempt to hand the American fort at West Point over to the British in 1780.) Eddy's merry band had burned the homes of some loyalists in the area, which naturally led to a whole lot of burning of non-loyalist homes by the British, after he had been chased away. As well as some Acadian families' homes, because, well, y'know. Any excuse.

|

British troops remained at Fort Cumberland until 1793, when regular troops were replaced by a "caretaker garrison." The fort was fully manned again during the War of 1812 (1812-1814), but fortunately Jonathan Eddy was dead by then, and no other American found it necessary to go after Nova Scotia this time. The British left Fort Cumberland for good in 1835, and the fort melted away for the next 80 years.

Until 1919, when the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada recommended that the ruins of Fort

|

|

|

|

Cumberland be preserved, due to their historic significance. All that remained of the fort at that time were a stone wall, brick foundations and the remnants of a powder magazine in the middle of a field, but the next fifteen years saw a courageous conservation effort (part of which was, fortunately, restoring the fort's original name). Fort Beauséjour was designated a National Historical Site in 1926, and was opened as a park with a museum in 1936.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|