|

Presidio La Bahía

Goliad, Texas, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1747 - 1771

Used by: Spain, Mexico, Texas

Conflicts in which it participated:

Mexican War of Independence,

Texas Revolution

Also known as: Presidio Nuestra Señora de Loreto de la Bahía, Fort Defiance,

Fort Goliad

|

The French really liked the Mississippi River. 'Twas Spanish explorers who first "found" this storied waterway in 1519, but French explorer Louis Jolliet (1645-1700), whilst exploring the Mississippi with Indian guides, discovered a relatively convenient backdoor to French Canada by way of the Illinois River in the 1670's...which made the Mississippi a valuable happenstance of water indeed for France. Wise Frenchmen mused that, could they just secure it, this river could be France's key to dominating all of North America. |

|

|

|

A series of French explorers "claimed" the entire Mississippi River Valley for France in the 1680's, hammering lead plaques into the banks of the river at intervals. These plaques stated that, if you're reading this, you're on French ground.

One of these Mississippi claimants was René-Robert Cavelier (1643-1687). Despite his many accomplishments in the field of North American exploration, Cavalier may not have had the firmest grasp of nautical navigation: Intending to initiate a colony at the mouth of the Mississippi River, he and his ships arrived instead four hundred miles to the west at Matagorda Bay, in the center of what is today Texas' Gulf Coast, in February of 1685. Could I have navigated any better? Absolutely not. In such a situation, I likely would have inadvertantly discovered Venezuela.

Instead of wowing his companions with the mouth of the Mississippi, Cavelier found himself at the mouth of Garcitas Creek. Did he try to convince the 180 settlers with whom he had made this voyage that this was, in fact, the Mississippi? "Je pensais que ça serait plus grand," at least one of them must have observed. Whatever, this merry band of Frenchmen decided to do what they set out to do (more or less), and built Fort Saint Louis as an anchor for their new colony.

|

A map of Fort Saint Louis expertly cartographied by a Spanish hand, upon that fort's discovery by the Spaniards in 1689. Was this fort armed with jalapeño peppers? As the scale of this map is unclear, anything is possible. A map of Fort Saint Louis expertly cartographied by a Spanish hand, upon that fort's discovery by the Spaniards in 1689. Was this fort armed with jalapeño peppers? As the scale of this map is unclear, anything is possible. |

|

As was generally the case, things did not go smoothly for this collection of pasty Europeans in the New World. Some semblance of a colony was duly scraped together, but a better spot five miles up the creek was shortly identified and the colony, along with its fort, moved there. Cavelier hung out for two years but then departed to do more explorin', with a promise that more supplies and manpower would be arriving shortly.

Further supplies never found the colony, but the Indians did. In 1689 the much-diminished French colony was wiped out, with only two survivors eventually making their way to French settlements in Arkansas. |

|

Completing the story of Fort Saint Louis, the Spaniards found its remains shortly after it had been destroyed by Indians. They burned whatever was left, and buried the fort's eight cannon, which the Indians had not taken, as Indians, historically, have had little use for artillery. Following this and other similar experiences, France pretty much gave up on Texas, concentrating its efforts instead in Louisiana.

But why have you even been subjected to this sad tale of a French colonial not-even-starfort, you may well ask? Because thirty years later, the starfort about which this page was composed was built atop what were probably the extremely diminutive remains of Fort Saint Louis.

|

Presidio comes from the Latin word praesidium, which means "protection" or "defense." The Spanish liberally sprinkled their expanding empire with presidios from the 16th through the 18th centuries. Some took on the mein of full-fledged starforts (The impressive Fortaleza de Hacho in Ceuta, Spain started its life as a lowly presidio), but most were relatively modest affairs, at least when compared to the starfortery of Europe. But the Spanish didn't just toss presidios around the world willy-nilly for no reason. They were built to protect missions, which were an important part of Spain's plan for world domination.

|

|

A whimsical depiction of Fort La Bahía from a Spanish map of 1789. Click it to see more, including another equally-impressive-looking starfort to the west at San Antonio...the Alamo! A whimsical depiction of Fort La Bahía from a Spanish map of 1789. Click it to see more, including another equally-impressive-looking starfort to the west at San Antonio...the Alamo! |

|

The mission that made the Presidio La Bahía necessary was the Mission Nuestra Señora del Espíritu Santo de Zúñiga. Established in 1722, this mission was intended to chip away at the local Karankawa Indians' understandable reluctance to embrace Roman Catholicism.

One distinct benefit that a small presidio had over a masonry fortification was that, when a more advantageous location was identified, the fort could be moved! Frequently! The Spanish built the first version of the Presidio La Bahía in 1721 in the aforementioned, on-top-of-the-ex-Fort-Saint-Louis location, but then picked it and its attendant mission up and moved them 26 miles west to the Guadalupe River in 1726. At this time it was manned with a garrison of 99 men. In 1747 'twas decided that a fort on the San Antonio River would be much better-placed to offer assistance to Spanish settlements on the Rio Grande, so our presido 'n' mission combo was moved, one final time, to its present location.

|

The Presidio La Bahía's lovely well, underneath which image I am required to include the following text, as per the Geneva Convention: ©wilsilver77/123RF.com The Presidio La Bahía's lovely well, underneath which image I am required to include the following text, as per the Geneva Convention: ©wilsilver77/123RF.com |

|

...and speaking of our presidio's present location, "La Bahía" means "on the bay," and this fort is nowhere near a bay...but it was, when it was first initiated in 1722: I promise.

The Presidio La Bahía's initial structure was certainly composed of wood and whatever else was lying around, but by 1771 it had been rebuilt in stone, and was the only Spanish fortification on the Gulf Coast betwixt the Rio Grande and the Mississippi. These days many a Spanish colonial fort is described as "the most important in its region," but this presidio may have actually been that important! And it was about to become even more important, because the early decades of the 19th century were tumultuous ones indeed for Spain's American possessions. |

|

It's easy to blame lots of historically upheavally things that happened at the start of the 19th century on Napoleon (1769-1821), and that's exactly what I'm going to do in this case: During the Napoleonic Wars, Spain was so preoccupied with allying with France, and then being a deadly enemy of France, and then being more or less taken over by France, that it had little attention left to pay to its colonies on the other side of the world. Already feeling unloved and ignored prior to these most recent wars which were tearing Europe asunder, Mexicans who had access to CNN knew that France, the United States and Haiti had all had revolutions, and had more or less thrown off the shackles of their imperial overlords within the past 30 years.

Accordingly, the Mexican War of Independence kicked off in September of 1810. Being occupado with this insurgency, Spain was unable to project much force into the Texas region, which left the door wide open for the forces that became known as filibusters. These were semi-military groups of American citizens who took advantage of Spanish discomfiture in Central America in the early-to-mid 19th century, by capturing places and things that the Spaniards were unable to defend, and then declaring those places to be independent republics. None of these expeditions ever proved successful in the long run, but The Presidio La Bahía was captured on at least two occasions, in 1813 and 1821, by furiously filibusterin' freaks. In all cases Spain managed to cobble together enough of a response to recapture the presidio. Somehow, when the smoke cleared in September of 1821, Mexico had defeated Spain, and was the world's newest sovereign nation.

And finally we reach the point of this story for which all Texans reading this have been impatiently waiting: The Texas Revolution. It didn't take too long for the white folks living in what became Texas to become displeased with Mexican rule. Though by most accounts the Mexicans were more than happy to welcome these industrious persons to their land, Mexico was less happy about the slaves that the Texians brought along with them. "Whaddya think is making us so industrious, Mexico?!" demanded the Texians. "You expect us to do our own menial labor?!" Slavery was illegal in Mexico, of which Texas was part, but this law was mostly ignored by its newest settlers.

|

Texians weren't all slaveholders of course, but one of the reasons that Texas became such a popular place to settle for Norteamericanos was because it existed outside the United States, where in the 1830's it was becoming increasingly difficult to own slaves when and where one might choose to do so. Among other reasons, it was for the "freedom" to own slaves that the Texians decided to break from Mexico. The Anahuac Disturbances of 1832 (which took place at and around Texas' only other semi-standing starfort that I've ever come across, Fort Anahuac) were the Texians' first acts of open defiance against the Mexican government. The Texas Revolution got well and truly underway in October of 1835, and a force of Texians immediately made their way to the Presidio La Bahía, with ill intent. Following a 30-minute battle, the presidio's Mexican garrison surrendered, and ta-daaa, Texas had a starfort! |

|

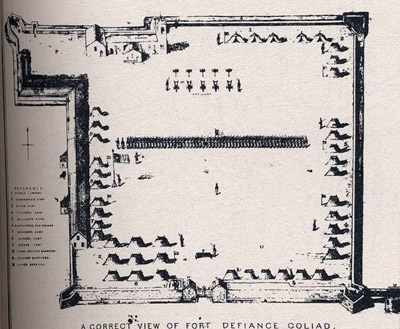

A Correct View of Fort Defiance Goliad, as it was correctly viewed in 1836...although I would take issue with the orientation: I don't know if presenting it as a diamond, as I have done at the top of this page would technically be correct, but it sure looks cooler that way. A Correct View of Fort Defiance Goliad, as it was correctly viewed in 1836...although I would take issue with the orientation: I don't know if presenting it as a diamond, as I have done at the top of this page would technically be correct, but it sure looks cooler that way. |

|

According to a sign at the presidio, Texas' first declaration of independence from Mexico was composed and signed by 92 citizens and soldiers at our presidio, on December 20, 1835. I didn't find any mention of this heroic document in any of the other sources I used for this page, which doesn't necessarily mean it didn't happen...and in general, I tend to give more weight to the information found on signs at the source, than Wikipedia.

Colonel James Fannin (1805-1836) of the Texan Army took command at our presidio. No self-respecting American (or Texan, presently) would call their fort Presidio La Blablabla, so the presidio of our present interest was renamed Fort Goliad, and then Fannin heroically (and defiantly) re-renamed it: Fort Defiance. Though caught on the back foot at the beginning of this conflict, Mexico wasn't going to let Texas go without a fight, and President of the United Mexican States Santa Anna (1794-1876) duly sent his European-flavored army to take back those things that he dastardly Texains had captured.

|

Not the Alamo: It's the Presidio La Bahía's chapel in the 1930's, in black & white, which is how the Texians would have seen it. Thanks as always for the ridiculously awesome supply of historic images, Library of Congress! Not the Alamo: It's the Presidio La Bahía's chapel in the 1930's, in black & white, which is how the Texians would have seen it. Thanks as always for the ridiculously awesome supply of historic images, Library of Congress! |

|

The Alamo, in San Antonio, was another Spanish semi-fortification that the Texians siezed early in the war, and was famously and bloodily reclaimed by Mexico in March of 1836. When the Mexicans first arrived on site in overwhelming numbers, the Alamo's defenders sent a plea to Fort Defiance, 90 miles to its southeast, for assistance. Fannin led 300 men and four artillery pieces on a relief expedition, but their wagons fell apart, everyone ran out of food and their oxen wandered off before they got very far from their starting point.

Fannin dejectedly dragged his troops back to Fort Defiance, and the Alamo was lost. Might history have been changed, had Fannin managed to put together a more robust relief expedition? |

|

Probably not; the Mexicans brought somewhere between 2,000 to 6,000 troops to the Alamo, and had Fannin's relief force even made it to the beleaguered fort, it would have boosted the number of defenders up to maybe as many as 500.

When the Alamo fell, Fannin was ordered to abandon Fort Defiance. Which he did, but his baggage train was so weighed down with nine cannon, 500 extra muskets and all the other stuff that humans need to exist, that it didn't take long for the Mexican cavalry to catch up. The Texians managed to form a defensive square and held off the cavalry into the next day, but were vastly outnumbered and surrendered to the inevitable.

|

Fannin and around 450 Texians were returned to Fort Defiance, where they were imprisoned. The consensus amongst the prisoners was that they would likely be released in a few weeks, but as of December 1835, Mexican law stated that armed foreigners captured in combat were to be "treated as pirates and executed." General José de Urrea (1797-1849), who commanded the troops that had captured the Texians, did not wish to murder them, and appealed to Santa Anna for leniency...but this was not the jolly old elf Santa, who surely would have spared the brave Texians. |

|

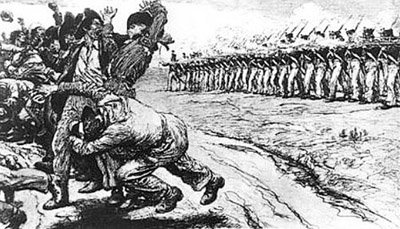

Goliad Executions by Norman Mills Price. Goliad Executions by Norman Mills Price. |

|

The group of Texians, which numbered somewhere betwixt 341 and 445, were lined up against what had recently been their fort, and shot in a most unsportsmanlike manner on March 27, 1836. Those who survived the initial fusillade were clubbed and/or stabbed to death...at least most of them. Somehow, 28 of these Texians survived the experience by feigning death...but Fannin was not one of those "fortunate" few. While Remember Goliad! may not have gone down in history with as much clarity of purpose as did Remember the Alamo!, Santa Anna's policies on executing prisoners in this conflict earned him an enmity amongst Texans which remains to this day.

|

Santa Anna and his army were decisively defeated by the Texians at the brief-yet-fierce Battle of San Jacinto (April 21, 1836), and Texas became a Republic shortly thereafter, when the Mexicans left (more or less) for good. Those in Texas wrestled over whether to apply for United Statehood, or to remain an independent republic...but our presidio, no longer situated near anything that needed defending, was no longer of much interest to anyone, and began a graceful slide into decrepitude.

Reconstruction of the Presidio La Bahía took place from 1963 to 1968, whereupon it was opened as a National Historic Landmark. Today, one can arrange to spend the night at the fort in "the Quarters," which have been reconstructed to appear as officers' quarters from the presidio's glory days.

|

|

|

Left: A Bahía garita!

Right: Yes I could have just slapped this image up instead of this entire page. Do you feel cheated that you had to read all that stuff above before you got to this succinct accounting? You're welcome. |

|

|

Many thanks to James, an eagle-eyed resident of Victoria, Texas who recently discovered the Presidio La Bahía in his own metaphorical back yard and was kind enough to share it with us!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|